Minecraft and its unexpected rise were like something out of a movie. In 2009, this rough, glitchy, blocky game was released to the public. In it, you romp around an 8-bit world, fighting monsters and building anything your heart desires. You know, when it wasn’t horribly glitching and doing outright weird stuff.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

The game was gradually refined over a series of pre-alpha, alpha, beta, and release updates. It went from being a hipstery college trend in 2011 to a cultural phenomenon. You probably have a sibling or cousin or child who plays the game on Xbox. We pretty much all do. That’s how massive this game has become.

For the uninitiated, the basic underpinnings of Minecraft are simple. You, the player, are dropped into a world that is infinitely large. You can walk forever and ever and – barring computer failure – the game will continue to generate new environments around you. Every Minecraft world is unique.

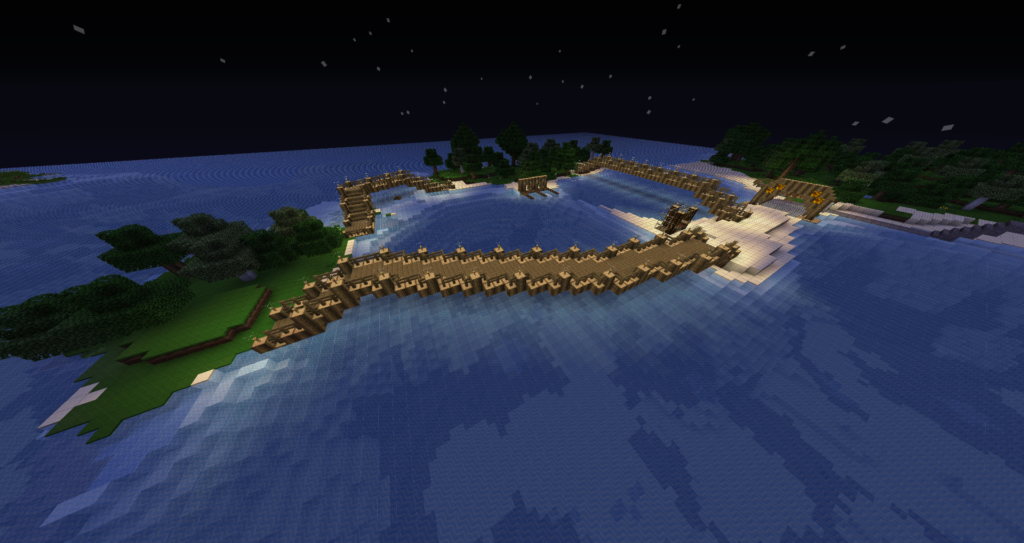

If you play the game alone, you have a few minutes to get basic shelter for the terrifying night time. Giant spiders, skeletons, and the dreaded and iconic creepers – who explode on proximity to the player – come out to play. Minecraft is a dangerous world. Yet once you conquer that danger, the game lets you take virtually any material you find in the environment and build with it. You can make elaborate castles, cities with roads and lights, train systems, farms, and more.

There is no objective to Minecraft. You just play. That’s why I think children love it so much. Beneath its unassuming exterior, there is an extraordinarily creative game.

I was really into this game in 2011 and 2012. I was obsessively interested in this game, at one point playing it for 12 hours straight during the finals week of one of my sophomore semesters of college. In fact, I actually made friends with a guy through Minecraft who introduced me to James Masino, the incredible artist who did the work for my first game, War Co.

It is for this reason that I am breaking down a video game instead of a board game for the second time in this blog’s history. I think we, as board game developers, can learn a lot from this game. Not only is it a good game, but it connects with players on a psychological level that most other games simply can’t.

Minecraft gives players little guidance, teaching players as they interact with the world.

When I started in 2011, Minecraft gave me no advice on how to interact with the world whatsoever. It just dropped me into it and I had to learn everything the hard way. Things have changed a bit and they have short tutorials now, but they still only teach you the basics. All the incredible things Minecraft has to offer – the complex architecture, the terraforming on a godlike scale…well, you learn that on your own. Minecraft shows players how to play through their own actions. There’s no info dump.

This gives players an incredible sense of achievement as they play. I’ve even got a scholarly article to prove it. Check out this mad knowledge from The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.

[P]erceived in-game autonomy and competence are associated with game enjoyment, preferences, and changes in well-being pre- to post-play. Competence and autonomy perceptions are also related to the intuitive nature of game controls, and the sense of presence or immersion in participants’ game play experiences.

That is actual, straight-up science saying that autonomy (freedom) and competence (skill-building) are critical parts of gaming that feels good. Heck, you can even find a host of studies that say the same principles apply to the workplace! Furthermore, intuitive controls allow players to build skills and play around freely.

How does this relate to board gaming? I think there’s a few takeaways:

- To give people a sense of autonomy, balance your game to where multiple strategies are viable ways of winning.

- To give people a sense of competence, make sure your game is understandable on the first or second play. Also make sure your game continues to reward people for playing 5 or 10 or 50 times.

- To make your game intuitive, use symbols, hints, and clues instead of preachy verbiage in your rule book.

Players see the effects of their actions on the game world and emotionally connect with the results.

Minecraft is notoriously, brutally hard when you first play. Yet it’s so addictive and rewarding because it gives you ample opportunities to learn and grow. Achievement is both defined by the player and hard-earned because of the forces of environment. All the blocks are so big that when a player sees the result of what they’ve done, they can’t help but emotionally connect with their efforts. Then they keep playing. And playing. And playing. (They call it Minecrack for a reason…)

The success of Minecraft teaches us about ourselves and our behavior. Despite its myriad flaws – the glitchiness, the love-em-or-hate-em graphics – this game remains one of the most perfect ones ever made. It’s the perfect sandbox, the perfect little “microcosm of life”, which is what I think games ultimately are.