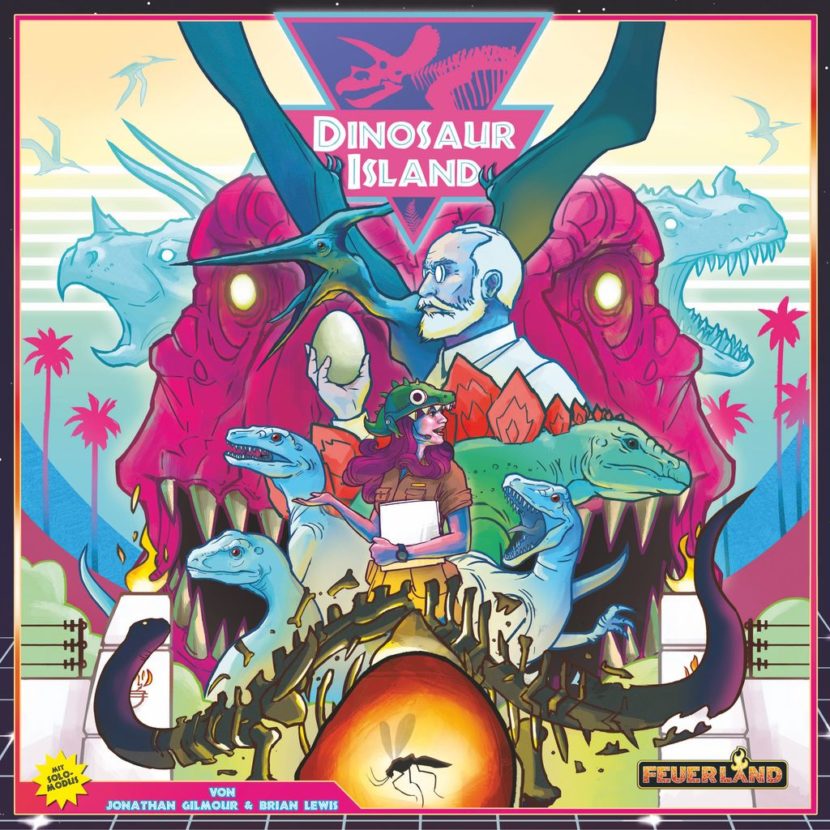

4 Lessons from Dinosaur Island for Aspiring Board Game Designers

A couple of years ago, Dinosaur Island was a massively successful game. It raised over $2 million on Kickstarter and stayed in the BoardGameGeek hotness for a really long time. Even now, two years later, the game’s name has enough cultural cachet to lead to the most popular board game giveaway Pangea has ever sponsored.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

For the purposes of this post, I’m going to talk mostly about Dinosaur Island’s superficial qualities. That entails theme, components, and art. While the gameplay is certainly good in its own right, I believe it’s the aesthetic of the game that led to its popularity and, as such, the lessons in this post are dedicated to analyzing that aesthetic.

With that in mind, here’s a quick overview of the game from Board Game Geek:

In Dinosaur Island, players will have to collect DNA, research the DNA sequences of extinct dinosaur species, and then combine the ancient DNA in the correct sequence to bring these prehistoric creatures back to life. Dino cooking! All players will compete to build the most thrilling park each season, and then work to attract (and keep alive!) the most visitors each season that the park opens.

1. Dinosaur Island nails nostalgia.

Take one good look at this game. You know full well which era is being depicted and which movie is being imitated. It’s no secret that Millenials – which represent a glut of the board game market – love 90s nostalgia (which is, indeed, their own childhood).

Let’s be clear. Nostalgia works. It’s an effective lever for making money. Dinosaur Island is extremely effective at monetizing nostalgia.

2. With a distinctive art style, you will stand out on social media.

At a casual glance, Dinosaur Island might seem like a throwback. After all, it harkens back heavily to the very 1990s film Jurassic Park and the Michael Crichton novel that preceded it. The resemblance even toes the line of plagiarism (though I personally see the game as more of a loving tribute).

Sure, the neon and pastel colors make you think the game was made somewhere between the end of the Reagan administration and the pilot episode of Friends. But it’s really not a throwback. In fact, Dinosaur Island has a distinctly modern art style calculated for the social media age.

So let’s say you’re a modern-day board gamer. You’re scrolling through your board game heavy feed. You see pictures of gritty, realistic sci-fi worlds and detailed fantasy universes. There are grim, dark games and simple, abstract games. Nothing quite looks like Dinosaur Island, though, so you stop scrolling listlessly and double-tap like. Others like you do the same and the buzz builds. This same principle applies to retweets, Facebook ad efficiency, your ability to spot the game across the room at a convention, and so on.

It pays to look different.

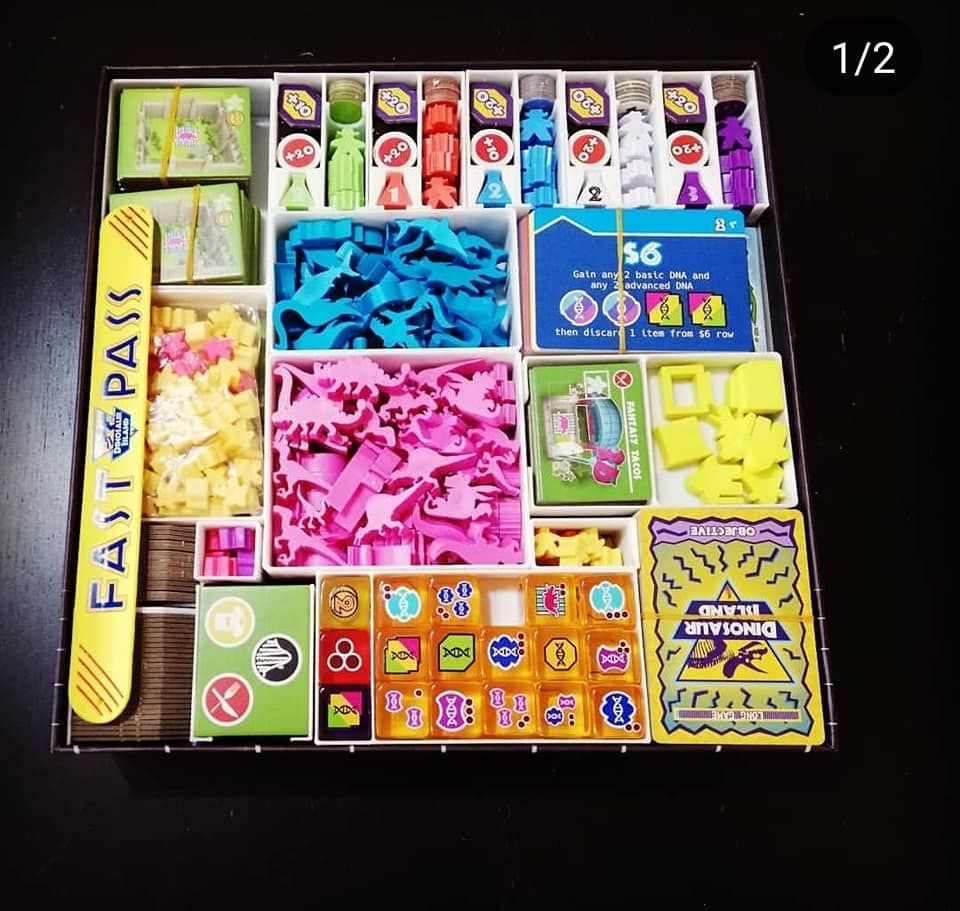

3. Respect the power of the custom meeple.

It seems I can seldom emphasize enough the importance of the tactile experience of board games. After all, our world is rich with entertainment options the likes of which our distant ancestors could have only dreamed. There are only two things that meaningfully separate a board game from its video game counterpart. The first is socialization in real life with other people, and the second is the physical experience of components. Only one of those comes in the box.

With this in mind, a keen observer of the board game industry will notice there are a bunch of ways you can create unique physical experiences. You can use creative three-dimensional gameplay like Colt Express or props like Ca$h ‘n Guns.

Custom meeples, too, are a popular way of creating a wonderful physical experience. In many ways, they are actually superior. They are often the most cost-effective components when it comes to crafting unique experiences, often costing as little as $0.03 or $0.04 per piece in bulk when carved out of wood.

Gamers love custom meeples, they’re cheap, and they photograph well. Hard to beat that!

4. No matter how pretty the theme, don’t skimp on the game.

I’ve spent the entirety of this post so far praising the superficial qualities of Dinosaur Island. It’s true – the success of Dinosaur Island can be largely chalked up to the way it looks. That means art style, components, and theme as a whole.

But don’t succumb to the cynical conclusion that you can polish garbage and sell it for $2 million on Kickstarter. That’s just not true. As seemingly illogical as consumer behavior can be, gamers are at least sophisticated enough not to buy a truly bad game. To believe otherwise is to reduce gamers to mindless consumer drones, which is simply not the case.

A quick scroll through comments on Board Game Geek reveals statements such as the following:

- “To my great surprise, this quickly became one of my wife’s favorite games… The theme makes it easier to teach, and once you’ve played a few times, the level of depth increases and you’ll really burn your brain at least a couple turns (but not too much).” – FranklinT

- “This is a very good eurogame which is easier [to learn] than it appears at first sight.” – Glasgow17

- “Jurassic Park the game is fun, light-hearted but heavy enough on strategy and a solid experience.” – Dudewiththeface

I interpret comments like the above as being indicators that the game meets at least a certain minimum expectation of quality. You see a lot of comments coming from people who find themselves in the unique position of being surprised by the quality of the game.

Not convinced? Consider one more factor. The number of board game reviewers with a truly substantial reach is pretty small and they constantly have to deal with a deluge of games. Many, upon reading rule books or playing a game, decline to provide a review when a game isn’t good. That didn’t happen here. If it did, the game wouldn’t have the reach needed to raise $2 million. So in summary, no – beauty cannot substitute for quality.

Final Thoughts

Dinosaur Island is a master class in branding through products. The game is keenly tailored for the audience it targets. Its art, components, and use of late 80s / early 90s nostalgia made the game stand out in a noisy world. From its success, we can all learn how to create games with enticing themes.