Over the holiday break, Maria and I found ourselves all alone, physically isolated from our family because of the coronavirus pandemic. After talking her family, to break the eerie silence of a just-ended video call, I said, “you want to pull out the old Nintendo 64?” Only upon literally breathing life back into the dusty old cartridges were we able to get it to start again: Mario Party.

Seeing Your Childhood Games with Older Eyes

Nostalgia is a good way to deal with a crisis, to be sure. I knew that it would be just the comfort needed for a disappointing holiday. What I didn’t expect, however, was just how well many of my childhood games held up. For one, I was surprised that they still worked in the first place, being over 20 years old now. But more to the point, I was impressed with how much thought and care was put into these classic video games.

I am almost 28, and that makes me older than many of the people that worked on these old games back in the mid-to-late ’90s. I’ve started to appreciate the games not just for their joyfulness and bright colors, but also their craftsmanship and attention to detail.

Think about it: these folks were working with brand new technology and had to experiment to figure out how games would even work in three dimensions. At the same time, the games could only hold 64 MB worth of data, so they had to make a lot out of a little. (This was true even at the time, as the comparatively sophisticated PlayStation 1 had CDs holding ten times that.)

Needless to say, I not only love these old games, but I admire how they were made. I think there are a ton of lessons to be learned from them, even for board game developers. Mario Party, as a series, has held up surprisingly well over the last 20-odd years. I played the first three over the last month, and the first one is still the best, despite the fact that it can be hazardous to your health.

How Mario Party Works

Before I get into the bulk of the article, here’s a quick overview of how Mario Party works. You and three other players, human or computer, go around a board. You collect coins which allow you to purchase stars. The player with the most stars at the end of the game is the winner, with coins being a tiebreaker if two or more players have the same amount of stars.

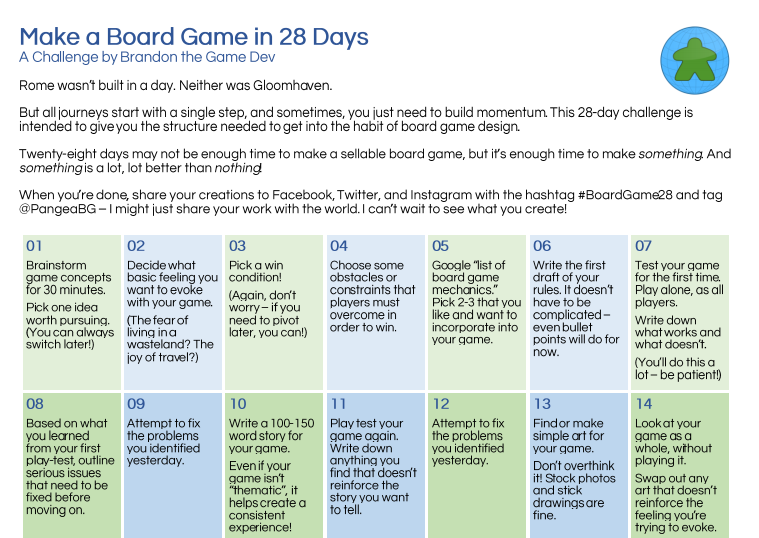

You can collect coins in a handful of different ways, including:

- Winning minigames (the primary way)

- Landing on blue spaces and avoiding red spaces (pure luck, but the board is primarily blue spaces)

- Stealing them from another player by visiting Boo

- Random events, such as landing on ? spaces, passing the board start, and others

There are many more nuances to the game, but this is all you need to know for the purposes of this article.

1. If you’re making a casual game, never let players lose hope…

Mario Party is a casual game through and through. After all, the game promised frantic fun for four players on its box. The social aspect comes first, and everything else comes second.

When you make a game that’s more suited for a social setting than a competitive one, you have to be careful not to let players lose hope. That means implementing a number of catch-up mechanisms for losers, even if that might irritate skill players. (This is, after all, why the blue shell in Mario Kart is actually a pretty smart design choice.)

Despite lavishing coins on skilled players through minigames, the game will never leave you high and dry. There are a number of catch-up mechanisms both subtle and obvious that never let you lose hope:

- You might get lucky and win a coin bonus when landing on a ? space.

- A random event might give you coins.

- When you pass Boo, if you have enough coins, you can steal a star from someone else.

- You might get paired with a powerful player in a team minigame, giving you a chance to win coins by being associated with them.

2. …but still find ways to reward smart play.

Mario Party, to be sure, has plenty of skill elements to it. Just about every minigame gives you a chance to win coins. If you’re a better Mario Party player, you’ll win more of those minigames. If you win the most coins in minigames, you’ll even get a bonus star at the end.

Plus, there are chances to make thoughtful decisions when deciding what direction to go on the board. Stars are randomly placed on the board and move every time a player gets one. Even still, a little knowledge of the game allows you to roughly predict where the stars will land and how you can best position yourself to get the next one.

For example, one tactic that Maria and I have both taken to is planning our routes around the Boo space. When know that if we get 50 coins, we can steal a star. Sure, it only costs 20 to buy it honestly, but the star is always moving. Boo never moves. That adds some stability to our strategy and lets us play a more predictable (if much meaner) game.

If you’re playing with Mario Party savvy gamers, you can even take things one step further. When paired up with a powerful competitor in a minigame, you can opt to throw the minigame, thus giving the prize money to the other players. In Mario Party 1, this is an especially effective tactic since losers in 2 vs. 2 minigames lose coins when they lose minigames. (This doesn’t happen in any other version of the game that I know of!)

3. Keep overall experiences consistent between games while the games themselves unfold in different ways.

Mario Party games always follow a familiar cadence. You roll a die, move some amount of spaces, everybody does the same, then there’s a minigame. Every once in a while, somebody buys a star. At the end of the game, bonus stars are rewarded.

There’s a rhythm to Mario Party and its a constant one seldom changed through the many versions of the games. Yet repeated plays don’t feel stale. Why?

Mario Party, for starters, has multiple different boards you can play on. Board games can’t usually do this, unless, of course, you’re using modular boards that can be rearranged.

On top of that, though, the star’s location changes frequently. That means you always have to plan alternate routes and your strategy may change on a dime.

Then, of course, the minigames are always randomly selected. Each Mario Party has at least fifty minigames. You all play a minigame at the end of each round, and there are between 20 and 50 rounds in each game (depending on the length of the game you sign up for). You’ll see some minigames three times and others not at all. It’s random and it always keeps you on your toes.

Board games often mimic the randomness I’ve just described in other ways. Mario Party moves the star’s location, and disease cubes in Pandemic are placed on different cities every round. Mario Party draws minigames at random, and Twilight Struggle deals out cards at random. Of course, Mario Party, Pandemic, and Twilight Struggle are all very different kinds of games, but the point is that you can introduce randomness into your board game in lo-fi ways. What’s more, it doesn’t even have to turn your game into a luck-fest, rather you can use it to make players think tactically on the fly!

4. If you’re using semi-opaque scoring, make sure it doesn’t feel like it’s coming out of nowhere.

A lot of Euro-style board games use semi-opaque scoring. That is to say, points are tallied up on the board in a way that anyone can see at anytime. However, additional points are rewarded at the end based on actions taken during the game. Terraforming Mars is a good example of this.

Turns out, Mario Party does this too. Each Mario Party awards stars at the end of the game, and in the first three Mario Party games, it’s always for the following three reasons:

- The coin star goes to the player who holds the greatest number of coins at any point.

- The minigame star goes to the player who wins the most coins via minigames throughout the game.

- The happening star goes to the player who lands on the most ? spaces.

Could you track who’s going to win each bonus star at the end of the game? Sure, if you wanted to. But most people will just intuitively have a guess as to who is most likely to get it at the end. That means the bonus stars are usually not surprising. They feel fair, even on the 10-20% of time where you’re caught off guard and end up saying, “yeah, I guess I can see it.”

5. Try stuff that might not work.

Looking at the original Mario Party, in particular, I’m most struck by just how scrappy it is. Honestly, it was not a good looking game at the time but it managed to age surprisingly well. Instead of using polygons for everything in the game, it relied heavily on matte paintings that, ironically, render better on modern TVs than old ones. This, of course, was a workaround due to the limitations of the hardware at the time.

Mario Party 1 wasn’t Super Mario 64 or Mario Kart 64. It wasn’t intended to be a blockbuster, money-making franchise. It was a rough, raw, weird little experiment that latched onto Mario’s popularity as a selling point. Yet it worked – not just enough to make the game profitable, but enough to make a franchise whose games number in the double digits.

I’ve often advised board game developers to exercise caution, test their games thoroughly, and to be realistic about their odds of financial success.

But at some point, you have to throw caution to the wind and try something weird. If you have to make a separate game to take risks in design, then do it. If you have to keep it to a tight budget and cut costs to put some creative concepts on cardboard. Give your strange ideas a chance to fly every once in a while!

Final Thoughts on Mario Party

Even after writing this whole article, I can’t believe how well Mario Party holds up to age and scrutiny. It’s an odd experiment that paid off and one that introduced untold millions of children to modern board game mechanics before the board game boom of the 2010s.

All in all, it’s smarter than it looks. It’s worth analyzing as craftwork, and not just as a child’s toy from a bygone era.