Carcassonne: Accommodating Different Play Styles

At the geriatric age of seventeen years old, Carcassonne is one of the elder games of the recent board game renaissance. It remains one of the most enduring, nuanced board games on shelves today. It’s the kind of game even your grandmother can learn to play (and also beat you at).

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

As with any game, it’s an exercise in self-control to put both my thoughts into focused, prosaic form and to limit myself to highlighting just one good quality. I will therefore focus on one of the qualities that lends Carcassonne its status as a classic: the ability to accommodate different play styles.

For those who have not played Carcassonne, here is a primer. Two to five players build the French village of Carcassonne, one tile at a time. The titles are randomized. Piece by piece, you define the features of the village: cities, roads, cloisters, and fields. Tiles must be built to where features are continuous – you can’t simply run a road into the city wall. (What’s wrong with you?!)

The objective of the game is to score the most victory points, which is done by placing meeples on features as they are being built. You score points for completed cities, road construction, and for surrounding cloisters in fields. You can also score fields, but that’s a little more nuanced, so I won’t get into that in this article. You don’t have many meeples to play, so you have to be judicious in their placement.

It’s a pleasant game. It’s pretty. It’s fun. It’s simple. It can be so nasty. It is this dichotomous nature that fascinates me so much with Carcassonne. You can base your strategy on two broad approaches: rising tides and zero-sum. The flexible nature of this game keeps it fresh, surprising, and exciting even as it approaches its twentieth birthday.

Let’s examine what these two approaches look like.

Rising Tides Carcassonne

It’s said that rising tides lift all boats. In Carcassonne, you can keep to yourself while you build long stretches of highway that net you ten or more points and megacities that net you twenty. You can create fields of greenery so vast that your farmers come back with wheelbarrows of points. You and your opponent(s) never have to conflict at all. You can all go your own way and the one who better manages their resources may well come out the victor.

Zero-Sum Carcassonne

Alternatively, you can fill your little French village with paranoia. You can trap farmers in tiny fields, leaving your opponents low on meeples for the whole game. You can curtail the growth of cities by placing tiles that close them off. You can put four-way stops in the middle of short stretches of highway. You can gridlock the countryside of France until nobody scores over thirty points. You can tease your opponents by cutting their opportunities down at every chance.

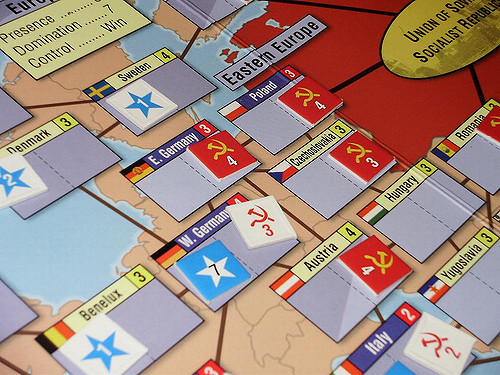

Even better? You can change approaches on a dime as it suits you. Is that not fascinating? So many games are so singular in their nature. There is no cutthroat version of Pandemic. There is no friendly game of Twilight Struggle (or War Co., for that matter). Yet Carcassonne can be both at once. If creating a game that can accommodate different play styles interests you, pick this game up. It’s about $20 on Amazon and you’re likely to be able to find it at a thrift store!