Colony: Letting Leaders Lead without Losing Losers (A guest post by Burt Yaroch of the Healthy Gaming Network)

Brandon:

The following is the second guest post by Burt Yaroch of the Healthy Gaming Network. Not only does he help gamers make healthier choices, but he’s a fledgling designer himself! Today he shares with us a game he really enjoys: Colony.

Burt:

I’ve fallen in love with Colony by Bezier Games, designed by Ted Alspach, Toryo Hojo, and N2 (the pen name for Yoshihisa Nakatsu). The engine building, the upgrading, the variable game construction, and even the insert are all fantastic! My wife asked me the other day if we could play it again and that NEVER happens in our household. My love of this game is what makes me forgive Colony for what I see as a major design flaw.

I believe this game suffers from one terrible flaw, which is ironically designed to reign in its “runaway leader” tendencies. What I have found in my plays of Colony and my research for this article is that this style of gameplay is unfairly criticized, and Bezier Games – understandably – attempts to compensate for this. I mostly like the way Colony handles this – with just one major exception! In this breakdown, we’ll delve deep into the enigmatic balance of leaders running away and losers catching up.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

What’s a runaway leader? Are runaway leaders always bad?

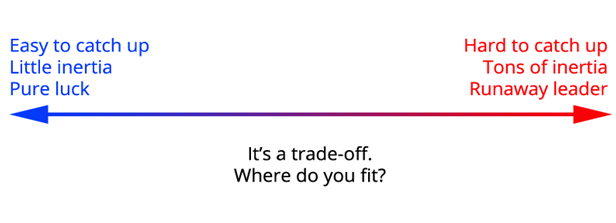

Let’s define some terms first. I’m going to use the term “runaway leader” to refer to a specific, purposefully included design mechanic. It is a mechanic by which the player in the lead position gains advantages that serve to move them further into the lead. To borrow from the vernacular of control theory, you create a positive feedback loop. The more you have, the more you get. The positive feedback loop snowballs until the winner is crowned. Colony has a “runaway leader” mechanic, but it reigns this in with different mechanics that act as counterbalances.

Carefully implementing a “runaway leader” mechanism provides players with a reason to get the points and resources early on for the promise of future advantages. Brandon has previously pointed out in his discussion of Monopoly, that too much of a “runaway leader” can be terrible. Too little, however, takes the steam out of the game. It gives you no incentive to do well early on. “Runaway leader” mechanics aren’t inherently good or bad – they are a design choice based on how designers want their game to play out.

Colony uses runaway leaders wisely…

Was Colony designed with a runaway leader mechanism? Absolutely. Players simultaneously build resource generators and victory points, the latter directly leading to a win. Having more resources leads to the ability to purchase additional resources more quickly which in turn leads to the faster acquisition of victory points. The person in the lead usually has the advantage (even though VPs may also be obtained without direct resource gain).

The designers of Colony likely asked themselves, “Is this runaway leader mechanism a bad thing?” I say “no” for two reasons.

One, the game is advertised at playing out in 45-60 minutes. If I fall behind and into a pit of despair, I only have to languish for a short time before my misery comes to an end. It’s hard for short games such as Colony to have a runaway leader “problem”, even if mechanics promote runaway leadership.

Board games must let leaders lead. To do otherwise is to patronize lesser players with participation trophies.

…and Colony handles runaway leaders with elegant “Catch the Leader” tools, for the most part…

The first “Catch the Leader” tool is Trade. It allows players to gang up on the leader. Trading in Colony offers a greater advantage than in a game like Catan, as here both participants can be rewarded with resources simply for the act of trading. Keeping the leader out of any trade deals will allow other players to close the VP gap and slow the runaway.

The second way players can selectively target the leader is through stealing resources. This not only limits the leader’s VP advantage, but also forces them to commit resources to mitigating theft, further chipping away at the leader’s lead.

The synergy of these mechanics make for smooth, fast, and fun gameplay where the runaway leader mechanic is not even detrimental in 3-4 player games, and only slightly so in 2 player games. In the dozen or so games I have played, most of the games were very close and none had players complaining about runaway leader or even considering it.

…But then Colony spoils their wise use of “runaway leaders” with a single, inelegant “Catch the Leader” mechanism that overcompensates

This begs the question of why Colony, with two Catch the Leader mechanics already implemented, includes the following rule: “Player(s) may discard one of his cards in return for a number of resources equal to the difference between his score and the leaders score.” Think about it. However far behind the leader I am, I can discard a card (which usually at this point in the game is irrelevant to me) and trade it for all-important resources IN EQUAL NUMBER to the distance I am behind the leader on the scoreboard! We intentionally play-tested this a few times just to see what would happen. It almost always turned a blowout game into a nail biter…and some into come-from-behind wins.

If the designers were concerned about runaway leaders, an obvious solution would have been to decouple resources from the VPs. Alternatively, they could have added further catch-up mechanics which fit into the theme and pacing of the game. For example, the Headwind mechanic from Dominion, a game which Colony resembles. This variable would slow down the leader’s progression as gaining VPs make future plays less efficient for the player.

Instead, the designers of Colony created an inelegant, unnecessary, and game-breaking rule that could be slapped onto any game’s ruleset to provide a Hail Mary pass. That is, if a Hail Mary counted as eight touchdowns instead of just one. If you play by this rule, all the gameplay comes down to a coin toss on the last turn – anathema to casual and hardcore gamers alike. I colored over both references to this rule in my rulebook with a black Sharpie. Out of sight, out of mind. Fortunately for all of us, games of Colony are usually so close that I can rarely see this being employed even by gamers who didn’t smite it from existence.

Parting Words: How to Let Leaders Lead without Losing Losers

If you want to make wise use of a runaway leader mechanic, here are my recommendations:

- If your game is under 60 minutes, don’t worry unless it’s really obvious. Gamers can handle a fleeting blow to their self-esteem.

- If you want leaders to be able to run ahead, you have to keep your game short – preferably under 60 minutes. When players feel like they can’t catch up, that is a great time to declare the victor.

- Remember the runaway leader mechanic is in the game because you put it there. Don’t like it? Nix it.

If the runaway leader mechanic is an accident, you have a choice to make. If you keep it in the game, you’ve got to mitigate with negative feedback (making each subsequent point on the board more difficult to reach). You still have to respect the effort of all players in the game.