Brandon: The following article is a philosophical guest post by Michael Heron. He’s the professorial mind behind Meeple Like Us, a board game review site with an academic focus on accessibility. His site is a good read, you should check it out!

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Michael:

Why, hello there. I didn’t see you come in. You caught me quite by surprise. Let me switch off my carefully intellectual classical music. I’ll just put down this dubiously large book of impressive philosophy that I was totally reading and not holding like a prop. What do you mean it’s upside down? Oh dear, what must you think of me? I clearly fumbled its orientation in my shock at unexpected guests.

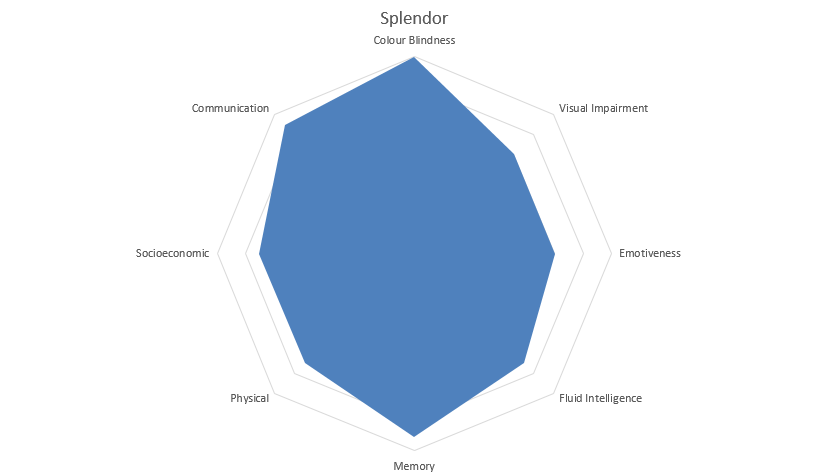

My name is Michael Heron. For the past year or so, I have been running Meeple Like Us. We’re a board game review blog. I know, I know – in gaming circles that’s like being a Hollywood barista working on a screenplay. Everyone is doing that – everyone fancies themselves a critic. What makes us different is that we dig pretty deeply into the accessibility of tabletop gaming experiences. Meeple Like us is part personal obsession and part research project. In real life, I’m a lecturer at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen, with a particular interest in the accessibility of games. Meeple Like Us is a series of ongoing notations regarding my work on that topic. For a blog I expected to be read by a handful of academics a couple of times MAYBE, it’s been surprisingly successful. That has been personally gratifying of course – as an academic I’m used to the readership of my papers being counted on the fingers of a single head. However, I think it’s also promising evidence that there is an appetite out there for this content – a desire to view and evaluate gaming through the lens of impairment and exclusion.

That’s a conclusion that should matter to any budding game designer, because it suggests what I believe to be a huge opportunity for the whole sector. Looking at the United Kingdom, the statistics are telling. Around 19% of the working population have some kind of identified impairment. Around one child in twenty is affected. There are five million pensioners with a disability. Two million people have sight problems. Scale those figures up or down for your own national context, and they tell you one thing – there are a lot of people out there with an impairment, or two, or more. That by itself might be merely interesting, but the thing that matters to you is that many of them want to play your games. It’s a massive market, and right now it’s not being well served. It’s a market that by and large doesn’t know yet they want to play your games because many of them believe gaming isn’t for them. That’s a perspective we can change. It’s certainly a perspective over which you as a designer have a great deal of power.

Many games won’t be accessible to everyone. That’s inevitable and to attempt to achieve genuine parity would create a prohibition around whole genres of games. Dexterity games will never be ideally accessible for those with physical impairments. Pattern matching games disadvantage those with diminished sight. Bluffing games require emotional confidence. Games with time constraints are an intersectional accessibility concern.

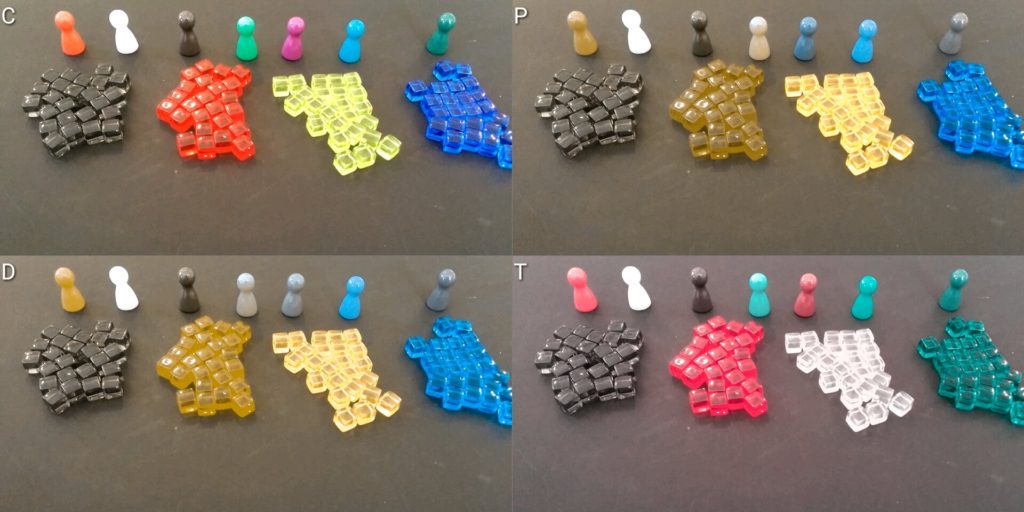

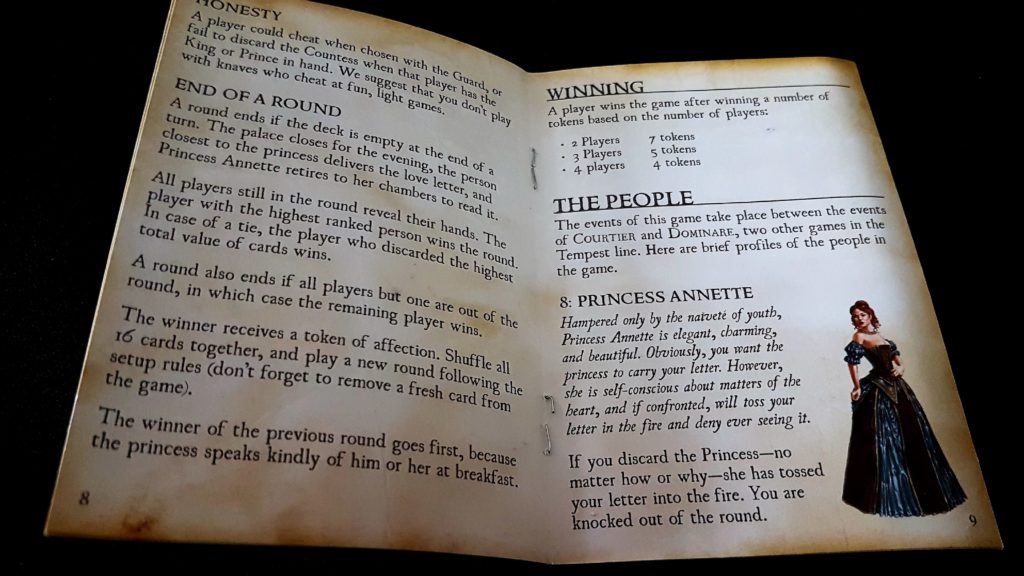

It’s important with accessibility that we understand how powerful small changes can be – we need not solve every problem in order to make a real difference. Disabilities exist on a nuanced spectrum – small changes here and there can open up audiences you didn’t even realize were available. The difference between using a 12pt font and a 14pt font can be “playable” and “unplayable.” Your choice of color might be the difference between someone being able to enjoy your game and colorblindness preventing them. Do you have a board? Do you include grid references? If not, you might be stopping someone from verbally expressing instructions in a clear and convenient way. There are lots of easy accessibility wins available. On Meeple Like Us, you’ll see many case studies of games where we discuss how the subtle interrelationship between components and mechanics can unintentionally exclude players. We would never advocate that you sacrifice core design principles in order to achieve universal accessibility. Some games, unfortunately, will never be accessible to certain groups of people. What we hope is that there is a great enough variety of accessible games, in all categories, that everyone can find something great to play with the people around them. A game need only be accessible for one group of players to contribute to that.

To that end we’re working on a set of comprehensive Tabletop Accessibility Guidelines – a document that will provide hints and suggestions for making accessible games. We don’t have it yet, because Meeple Like Us is a side project that must co-exist beside a demanding full-time job. It’s coming, though.

However, more important than a list of suggestions is for designers to adopt a wider perspective on who their audience may be, and the challenges they may face in playing their games. Accessibility guidelines are great, but accessible thinking is so much better. At its best, accessible design shapes a project from its beginning. Finding ways to make tasks easier to do, or information less costly to process, is always going to be easier when it’s not constrained by accumulated design. Designers that adopt accessible thinking will find it influencing every decision made, from concept to completion.

One of the things I’ve found over the past year is that there is a phenomenal amount of variety in tabletop accessibility. Tiny changes in game design may have remarkable impact on how playable the game might be. Accessibility guidelines won’t ever substitute for a deeper understanding of how people interact with the games you create. With Meeple Like Us, we’re building up a growing library of case studies that permit consumers to make informed choices, and game designers to see how tightly coupled their decisions are to the playability of their products. Our blog is a library – designers can pick a game that is similar in mechanics to their own, and see what issues we discussed. Simply knowing what problems other games have exhibited will illuminate parts of a design that may not have been at all obvious.

The good news is that most of the difficult work here is done for free once a designer decides to consider accessibility in a game. Most of the problems I see in the games we discus are not malicious. Nobody sets out to design an inaccessible game. I wouldn’t say the problems are due to indifference. The discussions I have had with game designers have been extremely positive once they realized the intention of the work. It’s not even that most designers are thoughtless – it’s that most designers haven’t realized there is anything of which they must be thoughtful.

If you are interested in developing an accessible game, you’ve cleared the first hurdle. Your own experience and empathy will help guide you towards more accessible thinking from that point on. You undoubtedly have friends with accessibility concerns. You may have older relatives with sight or memory problems. You might have nieces or nephews with a learning condition. Wouldn’t it be great if you could play your favorite games with them? Think of how valuable it would be if they could play your favorite games with you. We play games for many reasons – fun, critique, and competition. Mostly though we play them to make connections with the people around us. Whenever someone is excluded from play because of inaccessibilities, those connections are lessened.

It’s important that we understand when people are making comments about accessibility – they will almost never take that form. When someone says “the components are too fiddly,” they are making an actionable observation about your game. If they say there’s too much to remember, are there ways you can make the information challenge less intense? It’s easy to simply think, “Oh well – this clearly isn’t my audience.” The truth of the matter is that they could be if you acted upon what they tell you. Those friends and family are an information goldmine if you just dig it out of them.

Let’s not think though of accessibility purely in terms of impairment. Let’s think of it in terms of simple user design. There is little difference between an extraordinary person in ordinary circumstances, and an ordinary person in extraordinary circumstances. We are all impaired, at some point in our lives. Perhaps it’s a permanent impairment, such as the loss of a limb. Perhaps it’s a temporary impairment such as a broken arm. Perhaps it’s a situational impairment, such as holding an infant. We all benefit from accessibility in those circumstances. Accessible games are better for everyone, even if the benefit tends to be experienced more intensely by gamers with disabilities.

Finally, let us not forget the role that selfishness plays in the drive for accessibility. You may yourself feel the sting of age robbing you of the spring in your step and the dexterity of your fingers. The aging process is not kind – it usually takes more than it gives. Loss of physical precision and sight becomes increasingly common the older we get. Our cognitive processes change. Our hearing may degrade. When I’m older and retired – assuming such an institution still exists by then – I want to fill my days playing those games for which my real life obligations never permitted me time. I will only be able to do that if they’re designed with accessibility in mind. When we design for players with impairments, we design for our future selves. Let’s be selfish here – let’s promise Future Us that they’ll be able to enjoy the games that we create.

2 thoughts on “Why does accessibility in board games matter? (A Guest Post by Michael Heron of Meeple Like Us)”