How to Test Your Storytelling Powers & Make People Connect with Your Board Games

Board game development is a very individual process. Every single developer has different methods for creating their games. This article is the eighth of a 19-part suite on board game design and development.

Need help on your board game?

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

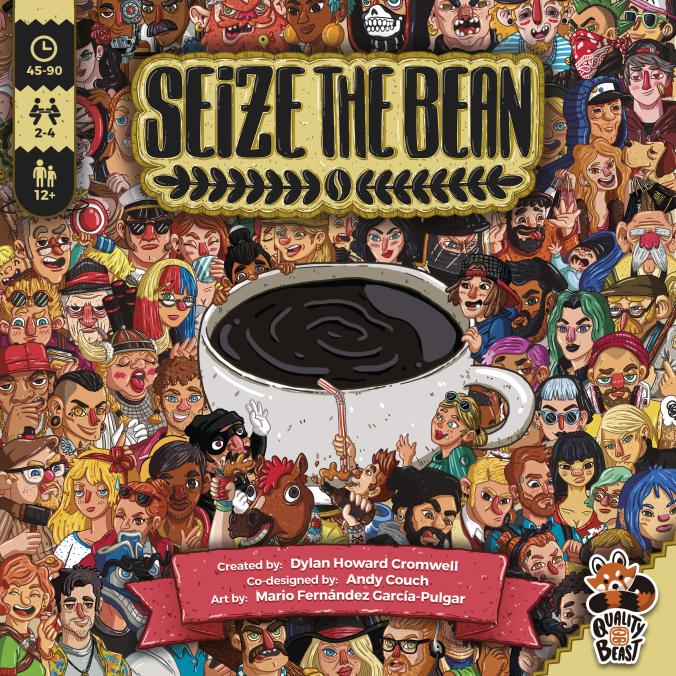

This suite is based on the Five Levels of Communication through Game Development, my own personal board game development philosophy. However, I’ve brought in Dylan Cromwell, the lead designer of Seize the Bean so that you can get two viewpoints instead of just one.

Just like last week’s article, we’re going to focus on what I call internal narrative. It is true that games speak to players through gameplay – the core engine, mechanics, and rules. However, when people think of storytelling in games, they think of theme, story, art, components, and even box design. The internal narrative covers everything about the game itself as a complete product minus the gameplay. That’s what we’re talking about today.

This guide comes in five parts:

- Play-testing storytelling

- How do we make stories that resonate?

- Art and storytelling

- Physical experience and storytelling

- Parting advice

Playtesting storytelling

Brandon: We spoke a lot last week about how to tell stories in board games. One thing we agreed upon was the necessity of making sure gameplay and storytelling fit together perfectly. This is true even for games that aren’t considered thematic. Even abstract games like chess have an intrinsic story to them. How do we play-test our board games to make sure our stories and our gameplay match each other?

Dylan: Wow, that’s a pretty intense question because there are certainly a lot of “right” answers. We could cover a whole series of articles just on the topic of proper and productive play-testing. I think one angle – epecially true for asymmetrical characters or seemingly unbalanced strategies, as is the case with Seize the Bean – is making sure you’re aware of at least a few of the player paths you expect or want to exist in the game.

Dylan: For example, the hipster customers in Seize the Bean have a simple, understandable mechanic that is directly tied to the theme and story: they make you raise your hype. Not allow you to, but make you. That means you’re drawing more customers into your line. This pushes the boundaries of what you can handle, resource-wise. So when it comes to the over-hyped café in real life that can’t handle the sudden explosion of business, you get that feeling in Seize the Bean if a player tries to go only for hipsters.

Dylan: Making sure this is working, though, requires myself and my co-designer, Andy Couch (as well as our game developers, Joder, Remigi, and Ninja), to actually implement that strategy during our weekly play-testing. We don’t look for every possible strategy. That’s not possible and it’s not our focus, but we do tackle the ones that make up the heart of the game.

Dylan: There are two other things which definitely take us into the realm of “basics of play-testing process.” I think they are important to mention, especially when trying to convey thick theme and rich story. Those are accessibility and graphic design.

Dylan: We had to get text sizing right. Colors were backed up by easily identifiable symbols. This is to make sure that all players could clearly see the information on the cards. The amount of people we’ve tested with who are color-blind or have sight issues definitely did not fit the statistic we’ve heard from manufacturers. If we didn’t make things accessible, they wouldn’t get to be immersed in the story as much.

Dylan: The second aspect is the general graphic design, especially when it comes to card effects or other mechanical symbols. We made the huge mistake of taking very verbose iconography to SPIEL17. We hoped people would “decode” the symbols themselves. In reality, everyone needed to look them up on a cheat sheet. If that’s the case, all of those 4 or 5 symbol strings can be reduced to a single symbol.

Dylan: This was massive because visual learners were totally shut out of the whole concept of upgrading their café with decorations since the verbal explanation went in one ear and out the other. It was made even worse because the cards were basically like hieroglyphics to them. They missed the benefit of doing so completely and therefore ignored this aspect of the game, eliminating this part of the story and experience for themselves.

Dylan: In summary: test a variety of strategies. Those are the stories your players will create. Test the accessibility because otherwise players can’t play those stories out. Test the graphics because otherwise players won’t play all parts of the game to discover those stories.

Brandon: A lot of the time you just have to test and test and test to make sure your mechanics and theme match up. You can then either change the theme or change the mechanics depending on what direction you’re going in. You can’t pursue everything – you and the team are wise to recognize that!

Brandon: Absolutely right that accessibility plays a huge role in making sure the story comes across. Failure to achieve a baseline level of accessibility can easily stop a story from resonating.

Brandon: Speaking of which…

How do we make stories that resonate?

Brandon: How do we make stories that resonate with others? I’m not just talking about making theme and mechanics consistent, I’m talking about making memorable stories.

Dylan: This is a great question and really applies to Seize the Bean. Not only does it claim to be about coffee, but it claims to be about Berlin, which is a pretty specific city. We ran into this early on: how will we make the theme and story universally relate-able enough that even people who don’t know Berlin can get into it?

Dylan: What we discovered was that it helps to find an overlap between your specific, unique story details and those that are more universally known. My previous example about hipsters is quite useful and another one would be tourists. Almost everyone can relate to a comical loathing of tourists, even though we’re all often tourists ourselves. The idea that serving a tourist in your shop might make other customers impatient and therefore leave or give you a bad review is pretty universally relate-able.

Dylan: Earlier on, we had our different customer groups bound to certain districts (neighborhoods) of Berlin. While this was super thematic it not only restricted our design massively, but it also ejected players who didn’t know those districts (and even some who did, when they did not agree with our categorization, such as loads of hipsters in Kreuzberg and loads of rebels in Friedrichshain). Once we removed the districts we had less design restriction and a much more accessible story for all players, not just those that know Berlin. For players who missed the districts we even found a way to include them, but I’ll let that be a surprise.

Dylan: Beyond making sure that your story is as universally relatable as possible, it’s also important to make it very unique. That’s the best way for it to be memorable. I think we’re all pretty tired of zombie games (except maybe Rahdo!), so another game about the rise of the dead is probably not going to be as memorable as a game about talking cabbages who are looking for apartments to rent. We discovered this early on with Seize the Bean, actually much to our surprise, that there weren’t that many games about coffee and especially not that many about running a café. This has helped the story of the game be more memorable as well, that it’s unique and doesn’t feel like a clone of another game.

Brandon: It’s a wise choice to focus on feelings and universal experiences instead of Berliner in-jokes.

Brandon: Similarly, I’m also making a game based on a specific location. I’ve had to strip Americana to its core feelings so I don’t alienate others. That means there’s no reliance on state names, an understanding of the country’s geography, or anything like that required to play. Likewise, I stuck to things just about everything can agree on: road trips are cool and we have nice scenery. All the other American in-jokes got the boot, now referenced only in low-key flavor text for those who pay attention.

Brandon: A good rule of thumb to make sure your stories work (whether or not you work on a game based on a particular region of the world)…

Brandon: Test with people around the world. If your basic messages work in America, Portugal, Spain, South Africa, China, and Japan, then you’ve probably made a story that is essentially human and not cultural in origin.

Brandon: (Testing through Tabletop Simulator makes this all a lot easier, by the way.)

Art and storytelling

Brandon: Before you ask for art and when you’re reviewing your artist’s work, how do you make sure your art supports the stories you’re trying to tell?

Dylan: Before you even ask for art, I think you need a discussion (internally with yourself or with your team if you have one) about what the art should convey; not literally, but what feeling, what mood. A lot of artists call the initial creation of this a type of assessment a “mood board.” It’s not that you have to visually make one, but get a sense of what would best represent your story. As I’ve said, Seize the Bean is meant to poke fun (respectfully) at all the wild diversity of Berlin, so having a cartoony, comical style would fit. Your game might need a more photo-realistic, painterly style, or even like War Co., a sci-fi, 3D style. Whatever it may be, nail that down and then go artist hunting.

Dylan: Once you find an artist (or a few), then it’s important to properly brief them about your work. We’ve learned this the hard way with Seize the Bean. Even though our artist, Mario Fernández García-Pulgar, has been a complete angel through all of our changes, we’ve definitely requested much more work of him than we needed to, due to asking for artwork far too early. This is a common mistake by first-time creators.

Dylan: When timing is right and your game is play-testing well and you’ve got your artist and they’ve seen your awesomely clear briefs, then reviewing their work makes sense. What I’ve found is that artists need space, but also benefit from a gentle nudge to challenge them a bit in how far they can take an idea. When I asked Mario for good and bad review tokens I simply had a thumbs up or thumbs down icon in mind. What he returned to me was brilliant: full on little comments from fake people!

Brandon: I’d recommend waiting until you have a working game and then picking an artist who you either a) know personally or b) whose portfolio fits your needs perfectly.

Dylan: This is great point, Brandon: having an existing relationship with the artist (actually, anyone on your team) is really helpful, especially if you plan to work remotely. For us, it was great for us because I had actually worked with Mario before on previous projects. And I already knew how he worked so we had a lot of trust. Trust is important because you should guide your artists but not control them. Listen closely when they aren’t feeling like an idea or direction is going to work. After all, that’s why you’ve hired them: for their expertise and creative vision.

Brandon: Artists love creative freedom. You give them flexible specs and watch them have fun. Correct a little as needed. I’ve seen great results by doing this.

Dylan: I always like to say it’s good to “let others surprise you” but great to “let them surprise themselves”.

Brandon: And yes, yes, yes, please listen to their feedback on visuals. That’s part of the benefit of hiring an artist. And this is so critical art is not only super important to feeling and storytelling, but it’s also a powerful marketing tool anyone can use.

Brandon: War Co. got sold on its art. Byways will probably be the same.

Dylan: Seize the Bean too, by far! And likely our next project for 2018, Towers of the Sun. All three of the artists on those two projects are just amazing. We’re very thankful to be working with them!

Physical experience and storytelling

Brandon: So let’s say you have a great story that matches your gameplay. Let’s say you have great art, too. A lot of solid games nail these aspects but slip up on components.

Brandon: How do you make sure your storytelling works physically and not just visually or mentally?

Dylan: Honestly, that’s been the hardest and at the same time, the easiest part of Seize the Bean.

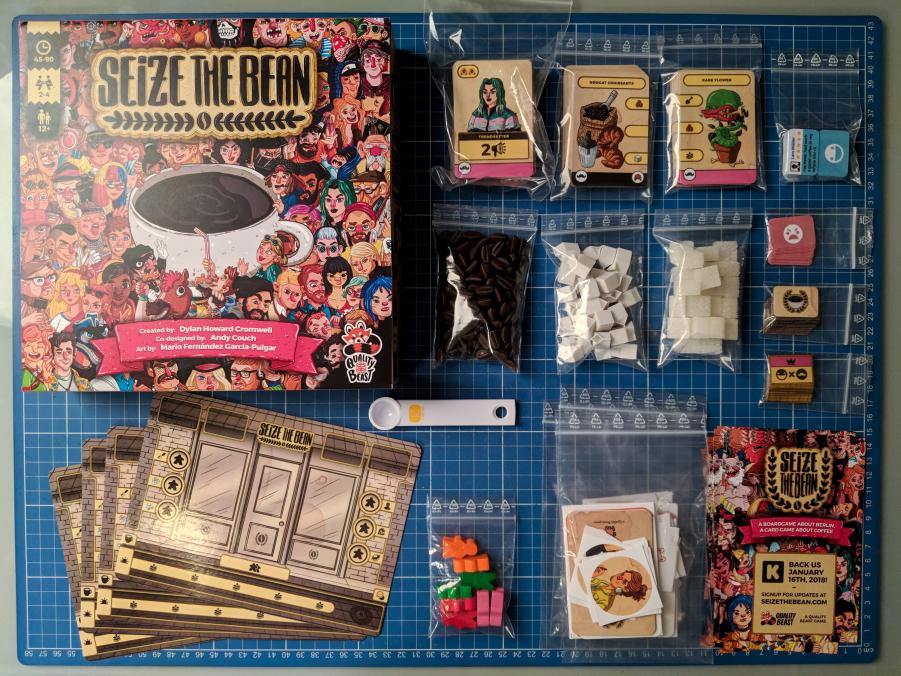

Dylan: Earlier versions were already wrapped in the idea of shop upgrades, coffee blends and various customers; those elements have always been there. But what I refer to as the game scope (whether or not you serve individual customers or a whole pile as a unit, whether you can have more than one shop, whether there is a big city map or a small image of a single café, etc) was unclear. While testing various game scopes and finally settling on the one we have, we noticed that 3D beans were awesome to play with but a pain to count in large quantities.

Dylan: Typically our scope didn’t require pay-out of beans in large quantities but it did often involve the initial purchase of them in large quantities. Therefore the physical, semi-dexterous mechanic (and component) of the scoop was born. As fun and silly as it feels playing with it, it solved a lot of serious physical issues early on. So in this sense, my business partner and fellow game developer, Josh Wilson (who was the one that dreamed up the idea of the scoop), identified the problem (too many things to physically count) and created a solution. The beauty here is the things (the beans) helped tell the story so removing them wasn’t ideal, and the solution he dreamed up also helped further tell the story so this was a win-win situation.

Dylan: Why do I say it was the hardest and the easiest? Well, adding in 3D components like beans and milk cartons and even our super realistic sugar cubes is easy. It’s also hard though because now that we’re going to Kickstarter on January 16th we’ll really require a critical mass of backers in order to fund those premium components. If not, we’ll need to find the best way to manufacture them more affordably, say with tokens. This won’t cripple the theme or story but it certainly won’t help tell it as richly. So that’s the danger of specialty components. Whenever you can, as creator, find a way to use economically sound components, you should.

Dylan: Another interesting physical bit of our process was card size. We wanted to get the feeling that a whole city of choices (customers, decorations and products) were out there on the table, but we didn’t want the players to need a huge ballroom table just to play. Therefore we actually looked to Feudalia for inspiration, and have been testing a 75x50mm card size that’s surprisingly worked out quite well for us. That’s something else to consider often; how can you modify the shape, size or other features of your components to better deliver your story? For us it was simple: get as much out on the table as we can, hah!

Brandon: It sounds like you’ve touched on the most important thing.

Brandon: Physical accessibility comes first. No matter how pretty it is, you have to make the game functional before anything else. Easy to use, easy to see, easy to count. Fail at any of these and your story gets lost in the shuffle.

Brandon: When you can add stylish stuff like beans, milk cartons, and sugar cubes without running up the manufacture price or losing accessibility, by all means, do it.

Brandon: The way you use parts is a lot more important than the parts you use. That’s why so many games are still using plain old plastic cubes, punch-out tokens, and so on. It works and it doesn’t hurt the gameplay experience.

Brandon: I will say, though: component upgrades make fantastic Kickstarter stretch goals.

Parting advice

Brandon: Okay, last question.

Brandon: If you go back to when you started in game design and give yourself advice, what would it be?

Dylan: There’s too many, why only one!? Hahaha…

Dylan: …but I think above all: don’t forget to have fun.

Dylan: That’s why we’re all in this, after all, isn’t it?

Dylan: I would let my past self know it’s gonna be a long journey: no matter how well you play-test, how perfectly timed your art briefs hit the artist’s desk, how costly your bits and pieces are, how big and friendly your fanbase grows to be…you’re in for a looong ride, so enjoy it. Do whatever you gotta do to make it something you love every step of the way.

Dylan: That, and maayyyybe drink a little bit less coffee.

Brandon: It’s a marathon, not a sprint. As a coffee fan, I can’t back you on drinking less coffee, though. Thank you very much, I look forward to sharing this!

Dylan: You’re welcome. Thanks for having me on-board the Brandon Game Dev express! It was a pleasure to chat about War Co., Highways & Byways, and Seize the Bean!

Telling stories is one of the most essentially human instincts. Whether or not we mean to, we tell stories through games. It’s best to embrace storytelling no matter how thematic your game is and perfect its tone. Through art, physical components, and clever use of language, board games can transcend their parts and become rich experiences.

In next week’s article, I’ll be bringing a special guest to talk about bringing everything together for your board game project – mechanics, rules, stories, and business. What does a board game look like when everything finally comes together?

For now, please leave your questions and comments about storytelling in games below 🙂