The 10 Most Popular Board Games and How They Made Gaming Better

Board gaming has a long, storied history that goes back to ancient times. You can find old games of Ur, Senet, and Chess carved out of stone and buried in tombs. Indeed, the modern board game landscape that we know and love is only about as old as Catan, which came out in 1995. There were popular board games long before then, though.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

I’m not too old myself – on the young end of the millennial generation – but I can remember a time of popular board games before the modern board gaming boom. Perhaps it’s Christmas Eve today that’s kindling my nostalgic impulses. I’d like to take a moment today and look back at the top-selling, most popular board games of all time. Some have aged beautifully, some have aged horribly, but in all cases we can talk about them and learn from them.

Honorable Mention: Life

Made in 1960, Life is one of the most popular board games of all time. The basic idea is that you want to end the game with more assets than anyone else. The rules are different in every version, but the concepts stay the same – you spin the spinner and make a handful of key decisions at intersections. It is in those moments that you influence which way your, well, life will go.

Life isn’t fair. It’s not a strategic masterwork nor is it a game that can be solved or analyzed. Honestly, it’s pretty luck-driven and messy.

Life does one thing exceptionally well, though, and we as gamers should be grateful. It lays the groundwork for modern, narrative-driven games. Life is, by definition, a game made on an epic scale. Players live out their entire lives on that board, with life-changing successes and failures coming at each step. Try to think of another game from before 1975 telling personal stories on a scale so vivid. I can’t think of one!

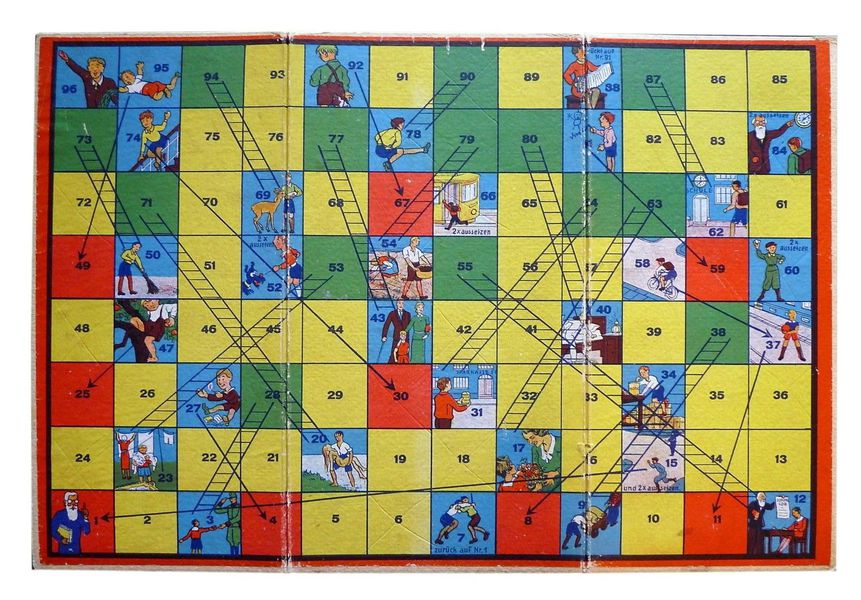

Honorable Mention: Chutes and Ladders (or Snakes and Ladders)

Chutes and Ladders is a lot older than you might think. Before being published by Milton Bradley in 1943, it was an ancient Indian board game that came from around the year 200 BC. The game is one of pure luck, and indeed, was used as a way to teach moral lessons. There is no strategic element to either the ancient or the modern version.

All you do to play Chutes and Ladders is spin a spinner and move the specified amount of spaces. Ladders move you up higher on the board and chutes drop you down to lower spaces. Modern versions still come with moral lessons.

With a derisive snort, some hardcore gamers may say “what did this game actually contribute to gaming?” As I see it, Chutes and Ladders gave us three gifts:

One: it was one of the few board games that had anything resembling a modern theme. Remember: in the 1940s, your popular board games were checkers, chess, backgammon, and Othello, all of which were abstract strategy. Yes, you had Monopoly, but that was a rare exception.

Two: along with Monopoly, it was one of the first appreciably “mass market” games. Without mass market games, you wouldn’t have hobby games. Period, point blank.

Three: strategically, the game is a snooze. Mathematically, it’s really interesting. Games like Chess, Go, Connect Four, and Chutes and Ladders are playgrounds for mathematicians. As they learn more, we as game designers absorb little bits and pieces of their wisdom and subconsciously incorporate them into our designs. Worth remembering!

10. Risk

Risk is a popular mass-market wargame that came to life in the late 1950s. The focus is on the oldest of human ambitions: to conquer the world. For most board gamers old enough to read this blog, Risk was the first game to introduce them to concepts like area control and influence – at least in a non-abstract way. Risk is a viscerally real game with success and failures spelled out upon the map for all to see.

This game laid the groundwork for other games of world domination, like Axis & Allies and Twilight Struggle. Yes, there are far better games out there today – including the two I just listed. But my takeaway? This is the game we owe gratitude to because it helped introduce the world to wargames.

9. Pictionary

Pictionary is super simple. Ultimately, it boils down to drawing a picture and others guess what it is. It’s like charades with drawings instead of actions.

The board is practically a vestigial organ to the game as a whole experience. The only thing that matters are the drawings and how people guess what they are. Anybody of any age can get into the game and have a good time – making it remarkably accessible and a fun way to pass the time. This game made Concept and Telestrations possible, and for that, we can be grateful.

8. Trivial Pursuit

Trivial Pursuit is a simple concept, and like Pictionary, the board doesn’t matter terribly much. The core engine of the game is fueled by answering questions about anything and everything. It’s basically every bar or restaurant’s trivia night boiled down into a single game.

It’s got a 5.2 on Board Game Geek, and to be honest, that’s not great. I think that’s a little harsh because it undersells just how much Trivial Pursuit brought to the hobby. Trivial Pursuit has over fifty special versions, which has laid the groundwork for games like Ticket to Ride to release multiple versions of a game based around the same engine. Trivial Pursuit swaps the questions and Ticket to Ride swaps the maps. The latter wouldn’t be possible without the former.

In any case, the prodigious growth of Trivial Pursuit as a franchise raised interest in party games, giving us delights like Balderdash, Codenames, and Dixit in the future.

7. Othello

Backgammon. Chess. Checkers. Go. These are all really, really old games. As such, they are pure abstract strategy games unmarred by the ephemeral themes du jour of modern board games.

Othello is not an ancient game, but it feels like it could have been even though it came out as late as 1883. Othello packaged up abstract strategy qualities into a new package, laying the groundwork for Santorini, Patchwork, Azul, Onitama, and other modern hits.

6. Clue / Cluedo

Even the most purely intellectual games like Chess or Go have elements of bluffing and deduction. You’re always trying to analyze your opponents’ moves and react accordingly. Clue (or for those of you who spell colour with a “u” – Cluedo), was the first mass-market game to make bluffing and deduction an explicit part of the game.

It is out of the mansion, yes – the very one where Miss Scarlet committed a murder with a lead pipe in the billiards room – that more sophisticated tabletop games that receive critical acclaim today were born. I’m talking about Mysterium, Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, and Mansions of Madness.

5. Monopoly

Nearly everybody I know has played Monopoly. Roll the dice, buy properties, pay rent to other players, and curse at the dice. It’s a well-known routine in the household of many people who grew up with board games.

Look, I’ll be honest. Monopoly is not a good game. It’s got a 4.4 on Board Game Geek and I’ve made my stance on it abundantly clear in the past. In fact, the game was created initially by socialists to show why unchecked capitalism sucks. Couldn’t make this up if I tried!

Yet it has served the hobby board game industry in two incredible and contradictory ways. First and foremost, it more or less made the market for mass market games. That, in turn, led to the hobby board games we know and love. We owe Monopoly our gratitude for this. In an alternate universe with no Monopoly, there is no Scythe or Rising Sun or Codenames.

Second, Monopoly managed to open the floodgates while being a decidedly broken game. It’s become the whipping boy of elitist hobby board gamers, so much so that it’s comical. In becoming a whipping boy, it’s shown game designers of our generation what not to do – helping many games avoid runaway leaders, an over-reliance on luck, non-judicious implementation of player elimination, and burdensome game length.

4. Scrabble

I’m going to stick my neck out for Scrabble. It’s got a 6.3 on Board Game Geek and I think that’s too low. It’s a smart, simple, and elegant game that uses the very elements of our language as components.

Scrabble is the foundation of just about every word-based tabletop game out there. That alone is an achievement for the ages, but I think there is something more important going on. In Scrabble, the pieces you work with are thrown into a bag and doled out by random chance. That’s the foundational quality of collectible card games like Magic. You can make maneuvers to benefit yourself and to block others – that’s an atypical form of area control and influence. Scrabble hasn’t so much created direct spiritual successors as it has burrowed its way into the psyche of game developers – coming out in subtle ways as they borrow mechanisms from this 1948 masterpiece.

3. Backgammon

Backgammon is one of the oldest games in existence. It’s estimated to be around 5,000 years old and was mentioned in written history by the Sumerians in Mesopotamia. King Tutankhamun was rumored to have played this game at one point.

Let that sink in.

Here we have this game, installed on just about every computer and available in every store, that was played in the Mesopotamian era. What’s more, it’s still a pretty good abstract strategy game and it stands the test of time. My takeaway here as that Backgammon is the great-great-great-great-etc. grandfather of every game we play.

2. Checkers

Checkers is a straightforward abstract strategy game for 2 players. Like a lot of games from antiquity or the medieval times, there is no theme per se, just a simple arrangement of pieces that follow some rules and allow for a battle of wits. These days it’s one of the first games that young children learn and it can be found outside of every Cracker Barrel restaurant sitting on wooden barrels. (It’s not as hard as the peg game, though…)

I’ve seen a lot of arguments online about whether checkers is a game of subtlety and nuance or a game of brutish simplicity. As for myself, I’ll readily admit its been many years since I’ve played the game. Whether you play all the time or remember the rules 40 years after you last played a game, you have to admit checkers has one astounding quality. It’s a tremendous game to teach children. If you want to start children out with a brainy game, checkers is a good place to start. Raise ’em up right!

1. Chess

Last but certainly not least, the best-selling game of all-time is Chess. It’s for great reasons, too. Chess has variable player powers, a sophisticated area control foundation, and endless possibilities of play. It’s captivated people from Humphrey Bogart to Joseph Stalin to the RZA. One could write volumes on the contribution of chess to the gaming community and to the world at large. I’ll keep it simple.

Chess has given us communities. It’s given us diehard fans who tweak their strategies, obsess, and seek ways to better themselves. Like no other game before it, chess has stoked passion and earned love. Chess has made livelihoods and Chess has caused deaths.

Try saying that about the latest CMON game 😛