Board game development is a very individual process. Every single developer has different methods for creating their games. This article is the first of a 19-part suite on board game design and development. I am going to teach you my own methods every week for the next four to five months.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

My board game design philosophy stems from the Five Levels model, which I created and explain in depth in Five Levels of Communication through Game Development. The basic idea is that board games are a means of communication that facilitate gameplay. This communication happens on five levels: the core engine of the game, mechanics, rules, the internal narrative or “theme”, and the external narrative or “community and marketing.”

This guide comes in three parts:

- What’s the core engine of a game?

- How do I come up with an idea for the core engine for my game?

- How do I turn the idea into a working game engine?

What’s the core engine of a game?

The core engine of a board game is what’s left when you strip a game of mechanics and obstacles. It is a mix of the objective of your game and the feelings you want it to evoke. The core engine is the bare minimum set of mechanics and concepts you need to have a functioning (but not necessarily fun) game.

Examples

Pandemic: The purpose is to wipe viruses off the face of the earth, save lives, and be a hero. The core engine involves this concept plus mechanics related to virus eradication. The movement, the classes, the geography, and so on are not part of the core engine – they are means to an end.

Carcassonne: The purpose is to build the best village. The placement of tiles is part of the core engine. The scoring and more finicky rules about tile placement are not part of the core engine – they are means to an end.

Twilight Struggle: You play as the US or USSR trying to win the war through strategic and tactical maneuvers. The core engine of this game relies on tension and area control. All the cards, the particulars of scoring, and the strategies are not part of the core engine.

Chess: Defeat the enemy by killing the king – that’s the core engine. The fact that you start with sixteen pieces and that pieces move in different ways back up the core engine as non-core mechanics.

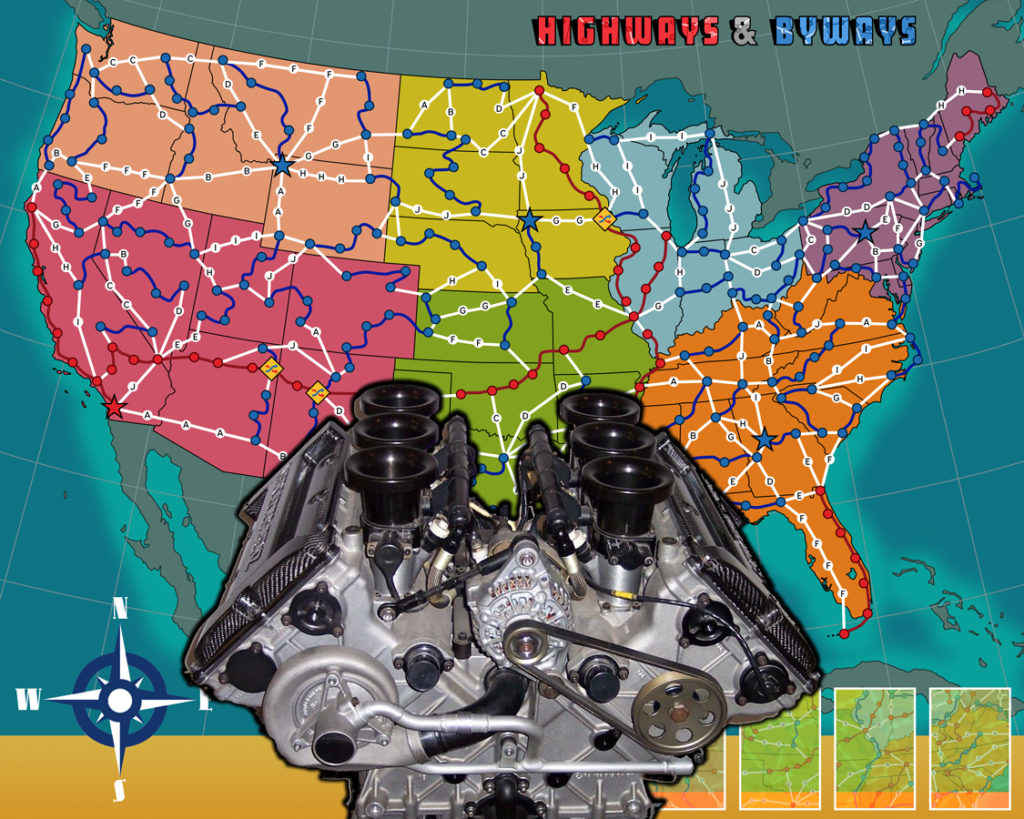

My own game, Highways & Byways: travel, explore, and move fast across the United States. That idea coupled with a board full of connected roads are the core engine. Every rule on how fast you can move, where you can go, and what can slow you down or speed you up is not part of the core engine.

You’ll notice that most of the games I just listed have a mix of basic mechanics and “theme” in their core engine. That’s no accident. You can’t take viruses out of Pandemic – it wouldn’t be Pandemic any more, even if it were functionally the same with a swapped out theme. The core engine is like a game’s “soul.”

How do I come up with an idea for the core engine for my game?

How do you know what your game’s core engine is? Well, it’s different for every game and every creator. Plus, if you ask gamers what the core engine of your game is, they’ll give you different answers. That means the core engine is an incredibly subjective matter that requires some introspection on your part. Don’t get hung up on perfection – it’s not possible here!

Your core engine centers around an idea. Here are some questions to help you come up with that idea.

Deep down, what do I want this game to be about?

I wanted War Co. to be a sinister game about the destructiveness and futility of war. Out of that, the core engine became slowly dwindling your opponents’ resources down to nothing and scraping by in the end with far less than you had to begin with. In order to do that, I needed some cards that followed simple, repeatable rules that allowed for the elimination of cards.

On the other hand, I wanted Highways & Byways to capture the feelings I had on my Great American Road Trips (yes, all caps is necessary). I gave it a sense of motion, travel, and exploration, because that’s ultimately what my road trips were about. In order to do that, I just needed a network of roads.

If your game were a statement, what would that statement be? Creators, whether or not they mean to, often build around messages. What I want you to do is take that vague vision and spell it out explicitly. By describing the game you want on the most basic level, you can begin to build around that. Mechanics, rules, and so on – they’re all just a means to explore that idea.

What’s the one thing about this game I can’t give up?

Sometimes you want to build a game around a mechanic. Sometimes you want to build it around a theme. Either way, there is something behind your desire there. Why are you so set on a specific mechanic or theme? What draws you to it? Spell out the basic emotions behind your desires and you may very well develop a core engine out of that.

What do I like to play?

If you think about the games you like to play, you will probably find that you’re drawn to certain mechanics and themes. Much like the previous question, that’s a sign you should think more deeply about the emotions behind those mechanics and themes. Why do you like them? Do you want to emulate them?

How do I turn the idea into a working game engine?

There is no easy answer for this. You can try creating the first thing that comes to your head. You can also try looking at Board Game Geek’s list of mechanics and picking out the ones you think will support your ideas. This is not an exact science – this is all on you.

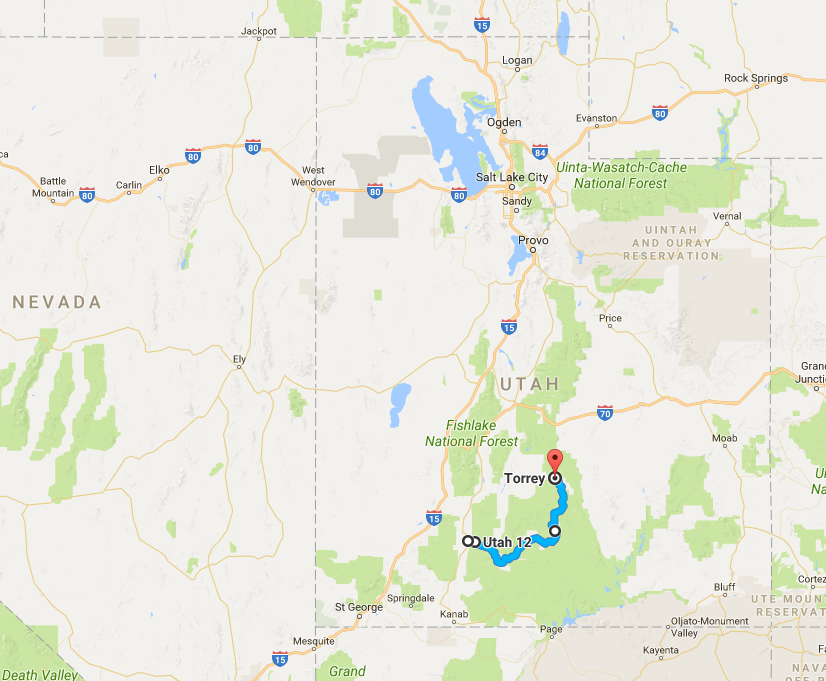

As an example, with Highways & Byways, I started Googling scenic roads in the United States. I pasted their shapes on a map. Then I drew lines between them for highways so the whole map was connected. Then I added spaces to regulate distance in the game. When I finished doing that, I had the core engine of my game. I was able to move pieces around the board. That’s it – everything else is just polish on top of the core engine.

When you take your basic idea and give it just enough to be able to do something, you’ve got a core engine. That can mean having a network of roads you can move a piece on without any breaks like in Highways & Byways. That can mean having a card game whose core concepts allow you to eliminate cards from your enemies like in War Co.

Final Thoughts

Game design is a notoriously imprecise science. Board games are entertainment, meaning they are based on emotion deep down, on-purpose or not. As a designer, you can benefit from consciously recognizing the emotions you want to evoke, articulating them into a basic idea, and building an engine around that idea.

Coming up next week, we’re going to be discussing how to play-test a core engine. Until then, please leave your questions and comments below 🙂

8 thoughts on “How to Design the Core Engine of Your Board Game”

This is a great article and has helped me overcome a personal “writers block” on my own board game. I especially appreciate the picture with the engine and how you stated “what’s left when you strip a game of mechanics and obstacles. It is a mix of the objective of your game and the feelings you want it to evoke.” If one is working on a lofty board game idea (like myself) it’s easy to get lost in all the mechanics to make it work that you lose sight of why you started to make it in the first place; the core engine. As you mentioned in another comment… “It’s like your thesis statement”.

I’m glad this article helped you, Luke! Sometimes, it helps to ignore the details (for a little while) and focus on the basic ideas you want to get across. Less intimidating that way!