5 Levels of Communication through Game Development

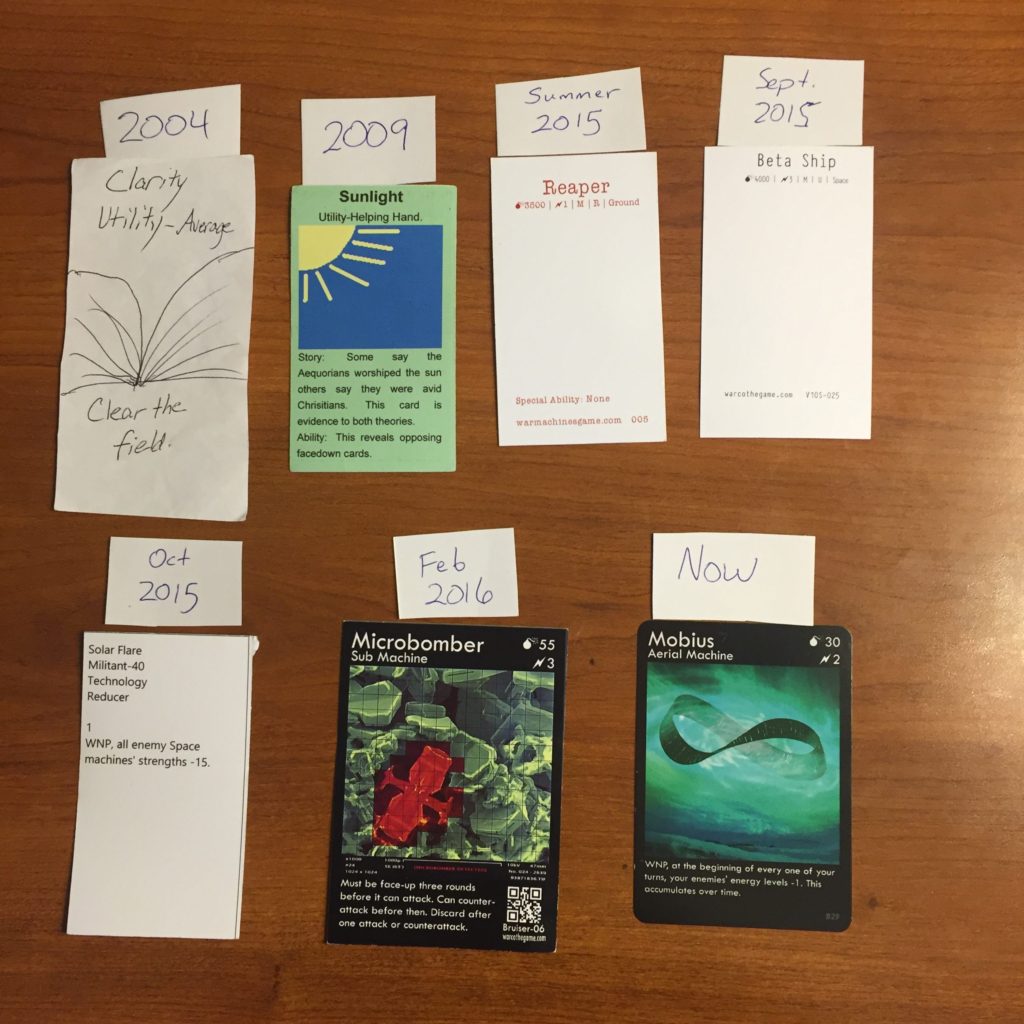

After spending a lot of time last week talking about how to make games, let’s talk about how to make them well. When it comes to games, there are a handful of truths that are very important to realize. Ideas don’t mean much. Execution is everything. Communication is key.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Ever since we were wandering around the earth, hunting prey and looking for caves, we as humankind were built to sense patterns. We were built to sense narratives. We were built to look for symbols. That nature is still within us. It comes out in subtle ways as we try to pick up new information, like when we’re on a highway in a strange town, meeting a new person, or playing a board game for the first time. We look for patterns and cues.

Sound like a stretch? I’m getting to a point with this. Sometimes you can be direct in your speech, saying exactly what you mean – such as in the rule book. But for the most part, your game needs to be “felt” more than “learned.” That is the only way to achieve the elusive and hard-to-define state of “fun” which we want our players to experience. That’s why I developed a theory which I refer to as the Five Levels of Communication through Game Development.

The following excerpt is from Games Speak through Mechanics, Not Rules (Dev Diary: 04/28/17)

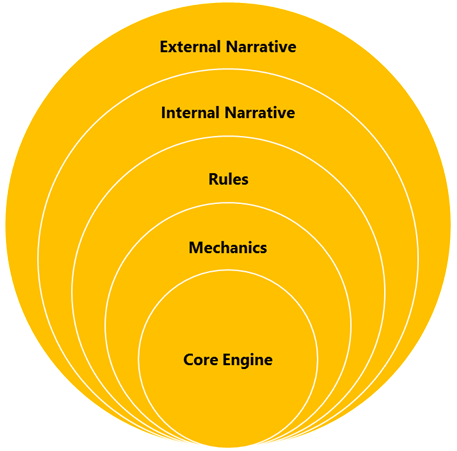

Games tell stories – whether they mean to or not.

Chess tells a story. Pandemic tells a story. These stories are told, on purpose or on accident, through five different levels of communication.

This is why when I create games, I aim to evoke a certain feeling. In the case of Highways & Byways, I want you to feel a sense of wanderlust, as if you’re a young person taking an adventurous road trip in a lousy car. There are five ways game developers can communicate the feeling they’re trying to convey. I’ll provide an example of how Highways & Byways addresses each.

Core Engine

If you strip out all the mechanics that put obstacles in your players’ path, what’s left? Obviously not a very good or deep game, but there is still the pursuit of an objective. The core engine is the bare minimum set of mechanics you need to have a functioning game.

In the case of Highways & Byways, the core engine is moving around the United States, aiming to travel a certain set of beautiful byways. It’s a game about travel, exploring, and being in motion.

Mechanics

Games are not very good until you have constraints that make it hard for players to achieve the objective. Mechanics should add obstacles – whether that means the game itself is working against you or other players are. Mechanics include things like player elimination and hand management. Sometimes you consciously create them and sometimes they arise out of rules.

In Highways & Byways, construction slows players down by making some highways periodically impassible. That’s a mechanic. Players draft their destination cards in the beginning, trying to cluster them as close as possible (and sometimes making it hard for others to do the same). That’s a mechanic, a form of hand management.

Rules

These regulate the way mechanics are implemented. The line between rule and mechanic is really thin, and people will argue about the precise nature distinction (or even the existence of a distinction). To me, a mechanic is the concept behind the game and the rule is the way that it’s handled to ensure balance.

Players draft destination cards at the beginning of Highways & Byways. To keep the drafting fair, there’s a rule that says “the first person to pick changes every time, going clockwise.” That way, nobody gets first pick all the time. Likewise, sometimes, you’ll draft something that’s really terrible. Everybody will then get a chance to “mulligan” 2 of 16 destinations they really don’t want to go to.

Internal Narrative

The game also speaks to players not just through the core engine, mechanics, and rules – which constitute the gameplay. It also speaks to players through its theme, story, art, components, and even box design. The internal narrative covers everything about the game itself as a complete product minus the gameplay.

Once Highways & Byways is farther along, I’ll be commissioning art, polishing up its theme, trying to find 3-D printed car pieces (if economically feasible), and making a gorgeous box. That’s all part of the internal narrative (which I haven’t even begun to flesh out yet).

External Narrative

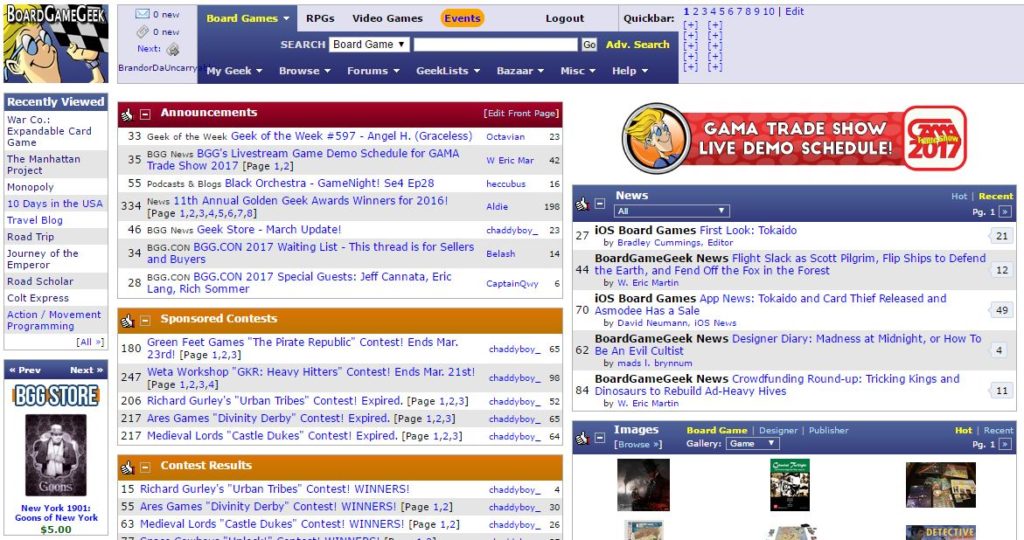

Games are more than just what’s in the box. They are also the marketing used to promote them – the advertising and the footwork of the game developers who made them. They’re the Kickstarter campaign and the stores they’re kept in. Games are the community that talks about them on forums and plays them at conventions. Games become everything that people claim that they are.

Highways & Byways is a game, but it’s also a series of blog articles, and a Twitter account. One day, it will be a Kickstarter campaign. I’m making this up as I go along and even as I write this very sentence. Everything I do online and everything others say online changes what this game means to you.

Putting it all together in board game development.

Every single level of communication is going to affect how your game is perceived. Screw up the core engine or mechanics, and the game itself will be bad. If you screw up the rules, people will be too intimidated to start, they’ll play it incorrectly, they’ll give you poor reviews online, or some combination of all three. Screw up the internal narrative, and you’re missing lots of opportunities to make your game more understandable, meaning it’s much likelier to be mediocre or confusing. If you screw up the external narrative, you could languish in obscurity, cultivate a bad community, or never get the feedback you truly need to succeed.

I’m doing my very best here to demystify what others would refer to as “art” or “chemistry.” I believe that making great games can be consistently done with a set of repeatable processes. Remember that the goal of game development has very little to do with your game in and of itself. You want people to have fun, socialize, and interact. You want people to escape their troubles for a while and engage in something fresh. Poor communication, at any level, is an obstacle to the desired emotions you want your game to evoke. Good communication is often felt, not heard or seen.