Bankrolling Your Board Game’s Development

Heads up: I’m going to be talking about money in lots of detail. You need to know this information if you want to self-publish, but I’m giving you a heads-up because money is a very emotional subject. This is one of the hardest, most soul-crushing lessons I’ve learned.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Creating board games can be an expensive affair. A lot of people do not want to admit this to themselves. In fact, minimizing costs is one of the most compelling reasons to create a game and send it to a publisher instead of self-publishing.

Self-publishing is expensive. My friend, Garret Rempel of Tricorn Games created a small print run of a single-deck card game called Go Fish Fitness. This is the simplest viable game you could possibly make in the hobby board games industry. It cost him close to $3,000.

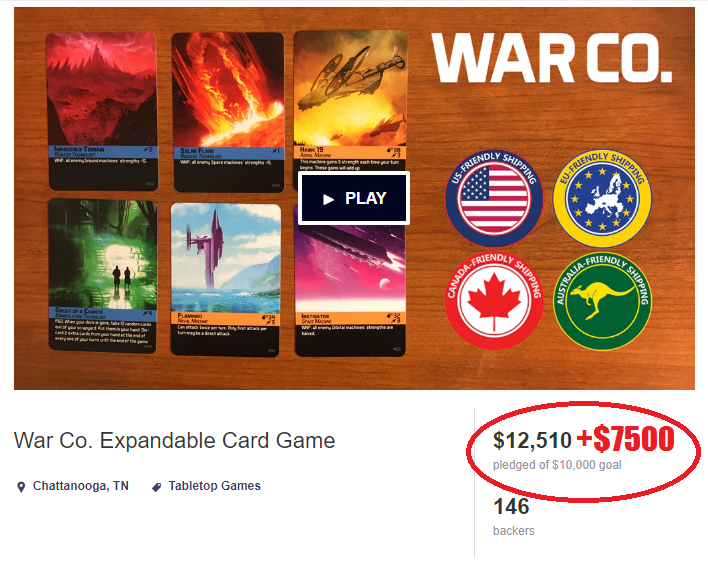

In this very same article, I go on to say that War Co. cost nearly $20,000 to create. Of this, $7,500 was out of pocket and it took me a long time to make it back! I was working a full-time job in an IT job that I got after graduating with my MBA when I started working on War Co. I saved up a little money every two weeks when I got paid to make this game happen and I still ended up paying quite a bit more than I expected. In the end, I paid to create an entire game with high-value art before going to Kickstarter to get manufacturing costs covered.

I know not everybody can pay thousands of dollars to make a game with no guarantee of getting it back. I’m by no means rich, but I do make solid money and I live in the southeastern United States where the cost of living is low. On top of that, I live a low-cost lifestyle in a small house with a used car in an okay neighborhood. That’s how I manage to do it, but I know that frugality has limits.

So if you can’t save up tons of money to make a game, you’ve got two options:

- Go through a publisher.

- Make something lightweight, like a small card game.

I won’t go into detail about the first option. I do know a handful of personal friends of mine who have succeeded taking option two: Garret with Go Fish Fitness and Weird Giraffes, the team behind Super Hack Override. Both of them made modest Kickstarters, succeeded, and are working on their next games.

To be honest, this is a much more reliable path than what I did with War Co., which was expensive because it was a six-deck game instead of a one-deck game with 300 original pieces of art. The massive scale of the game and the variety of art are now selling points of the game, so it worked out okay. Yet it’s more sensible to set a low goal for your first game or two and gradually work your way up to bigger ones. I tilted at a windmill to make a childhood dream come true. That doesn’t mean it was a financially sound decision.

The Limits of Crowdfunding

“I can just Kickstarter to pay for all the setup costs, can’t I? Do I have to do what you did with War Co? I can get them to pay for my prototyping and art!”

Maybe. It’s just incredibly unlikely. Take a look at successful Kickstarters over $2,500 and tell me how many of them do not have the majority of their art done by the time they go to Kickstarter. Your game needs to be 90-99% done before you go to Kickstarter. Your game needs to play well, look beautiful, you need to have an audience, and you need to keep just a little wiggle room for your Kickstarter backers.

Let’s also take a moment to put another myth in the ground. You probably won’t make a profit on Kickstarter. You have to understand, Kickstarter and their payment partners take an 8-10% cut of whatever you make AND backers generally expect a lower price than retail since they’re going to be waiting a long time for a project they can’t be sure they’ll receive. That’s going to put the squeeze on you. Your goal on Kickstarter should be to break even on Kickstarter costs. Don’t try to recoup your equity and don’t try to make a profit. Give your customers a good experience, buy as much inventory as you can with the Kickstarter money, and sell the rest later.

What Will it Cost?

Costs are highly dependent upon the type of game you are creating. There are costs that come prior to Kickstarter and costs that coming after Kickstarter. If you decide not to use Kickstarter or a similar crowdfunding site, you’ll be bankrolling the entire project yourself with no help. If I had to ballpark the cost of projects, though, here’s what I’d say:

- $3,000 for a card game with 1 deck and 50 cards per deck

- $1,000 for set-up costs

- $2,000 for a modest Kickstarter

- $12,000 for a simple board game with modest art demands

- $5,000 for set-up costs

- $7,000 for a modest Kickstarter

Of course, it’s a little silly to ballpark project costs in the abstract. Every project is different, every set of needs is different.My guesses can only help you narrow down the “order of magnitude” of your project.

Here are some things to consider:

- How much artwork do you need to buy? (Before Kickstarter)

- What components are you using? (Before & After Kickstarter)

- Where will you have your game made? (After Kickstarter)

- How much will your game cost to fulfill? (After Kickstarter)

Before Kickstarter

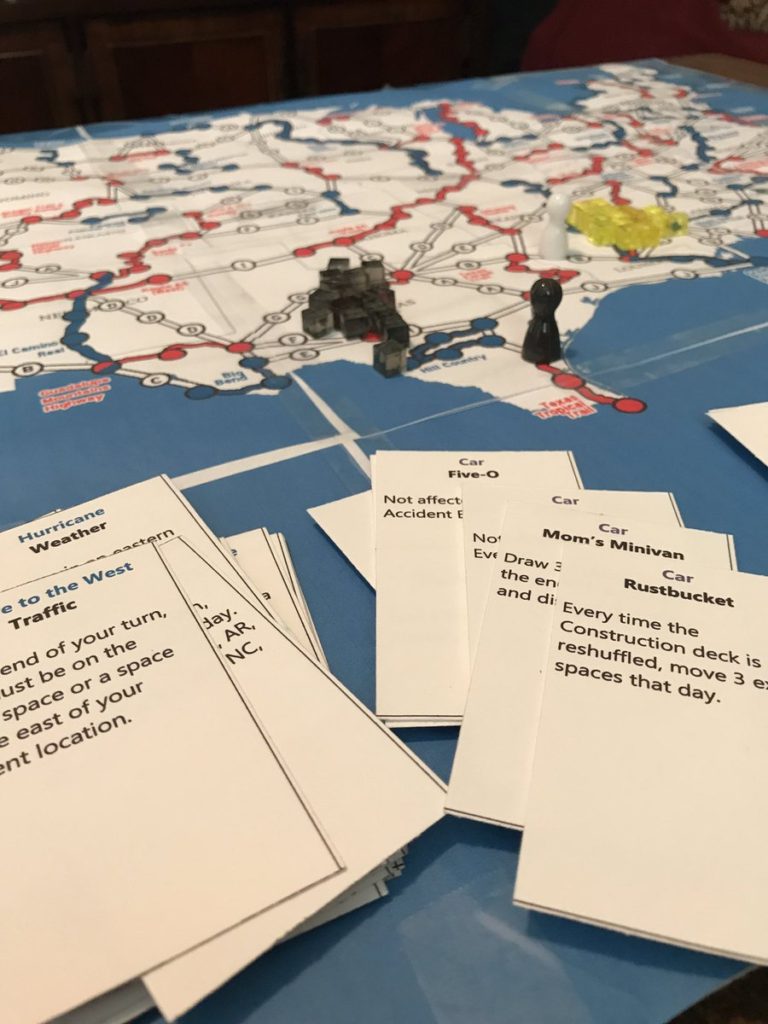

Development Costs: Depending on what you use to create your game, you might end up incurring a shocking amount of costs in paper and ink. Yes, stationery costs add up! I spent hundreds of dollars printing out War Co. cards before I found the free tool LackeyCCG. Even after I started using LackeyCCG, sometimes I still printed fresh cards because it felt better than using digital tools.

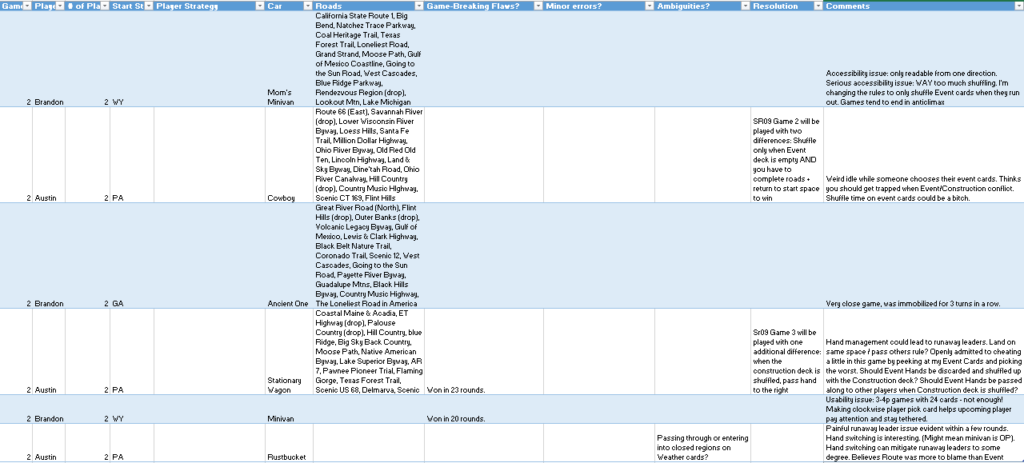

Prototypes / Testing Costs: Of course, at some point before you run your game by reviewers, you’ll need to get a sample of it to make sure it feels good physically. You want to make sure that you can use all the pieces, that everything looks right once it’s printed, and that there are no major accessibility issues. Running a single copy of a game is kind of expensive. Running 10-20 copies for reviewers and then paying for the shipping to send them (even within your own country) can add up to hundreds or possibly even thousands of dollars. For War Co., prototyping for my own purposes and for reviewers was around $500.

Administrative Costs: You’ll want to get a business license before you use Kickstarter. I suggest keeping it simple and being a sole proprietor if you’re a solo dev. Consider an LLC if you’ve got a team of two or more, but make sure you really understand what you’re getting into before you sign any papers. You’ll need a bank account for your business. You might need some software or a new computer. You might need plastic storage bins for your game. This can add up to unpredictably high costs.

Advertising Costs: Some people use online advertising to draw attention to their business. Costs are highly variable by channel and by your budget, but this might also be something you want to factor in.

After Kickstarter

Kickstarter Costs: No matter what, Kickstarter and their payment partners are going to take 8-10% of your campaign funding for fees. So it goes.

Fulfillment Costs: Additionally, it will cost quite a bit to get your game to your customers. It’s not unrealistic to think that it will cost 20-30% of the reward price. Account for that.

Manufacturing Costs: This is probably going to be the bulk of what you use your Kickstarter funds for. Go for the amount of money you need to make the smallest print run that makes financial sense.

Something you should look out for when you’re getting your game manufactured is the “landed price.” If you take your printer’s quote and it comes out way low, you might be missing some details. There are three parts to the landed price: manufacturing, shipping, and customs. Manufacturing is the cost to actually make your game, shipping is the cost to get it to your fulfillment companies or to your place of business, and customs is the price of moving inventory across a country border.

Most places want you to do a run with a minimum order quantity (MOQ) of 500 or higher, so be ready for that. If your game has a landed cost of $10 for each game, that MOQ will cost you $5,000 once all the costs are totaled. Costs start dropping at higher order quantities, but just focus on clearing the MOQ hurdle when you’re starting out. You can use the little cost reductions to add things like stretch goals to a successful Kickstarter.

A Special Word about Taxes

This differs by country, state, and city. You need to talk to a pro about this. But I have one ESPECIALLY important bit of tax advice for you. I’m not a tax expert. I just went to the school of hard knocks on this.

Inventory is taxable. If you follow my prior advice of using the Kickstarter to break-even instead of making a profit, Kickstarter taxes won’t be so bad. In general, taxes are calculated like this…

Tax Paid = Tax Rate * (Revenue + Change in Inventory – Kickstarter Costs – Setup Costs)

So if your tax rate is 30% (a good guess in the United States for sole proprietors) and you make $20,000 on Kickstarter, spend all of it on the game, wind up with $12,000 inventory, and it cost you $8,000 to make the game, this is what will happen…

$1,200 = 30% * ($20,000 + $12,000 – $20,000 – $8,000)

That can be a painful experience if you’re not expecting it. Because, after all, you feel like you’re still out by $8,000 since your money is tied up in inventory. But if we simplify it a little more, here’s what’s going on…

Tax Rate * (Inventory Value – Money You Haven’t Made Back Yet)

$1,200 = 30% * ($12,000 – $8,000)

You need to either be mentally ready for this when it happens OR set aside cash.

Pinching Pennies

It is really hard to start a business. Many say it takes 3-5 years to do it right and it can be a nerve-wracking experience at first. It takes a ton of time and a lot of smart money management. Thankfully, your old friend Brandon has made plenty of blunders so that you don’t have to. There are a lot of ways you can save money on your early game projects.

I’ll close with six suggestions that will reduce how much it costs to make your game.

- Reduce research and development costs by using an inexpensive online game testing tool such as Tabletop Simulator.

- Reduce art costs by looking for sophomores and juniors in local art and design colleges. They often will often do work for a much lower cost if you make sure to give them a project that will accelerate their career.

- Keep a separate bank account for your business. Try to get big gains and big losses in the same year – it can save you big tax bills if you’re using cash accounting (which most people do by default).

- Research fulfillment companies extensively to find ones who will fulfill your Kickstarter for the lowest costs.

- Research manufacturing companies extensively to find ones who will create your game at a satisfying level of quality for a low cost.

- Instead of paying for advertising, get really good at social media and build a mailing list. Here are some articles to help you out with that.