A Crash Course on Kickstarter for Board Games

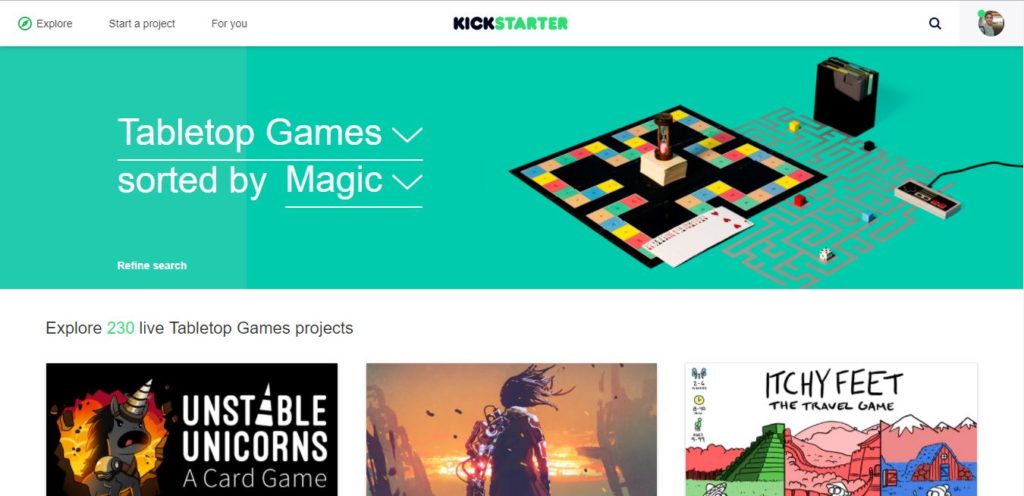

Kickstarter. The name alone evokes a lot of feelings in hopeful entrepreneurs and board gamers alike. Whether or not you’ve backed or started a campaign, you probably have an opinion about the site. At the very least, you probably share the sort of ogling fascination that people inevitably experience when they first hear about the site.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Kickstarter isn’t a magic money machine.

“You mean you can put your business idea on there and people will just pay for it? OMG!”

Well, yeah. That is how it works when you look at it from a distance. Yet up close, this initial impression almost entirely wrong. Sure, tabletop games made $113 million on Kickstarter in 2016. A surprisingly high 55% of board games managed hit their goal, which appears incredibly optimistic for entrepreneur hopefuls. A lot of tabletop game Kickstarters, however, come from people who are:

- a) representing established companies who use Kickstarter effectively as a pre-order system

- b) repeat campaigners who have already succeeded

- c) developers who have done a ton of research and know what they’re getting into

For these reasons, Kickstarter is a lot harder than it looks. If you’re a first-timer, it’s really hard to break into. That’s why I’m here: I want to help you succeed in getting your board game project funded on Kickstarter the first time you try.

I am writing this guide for beginners. It’s going to be an overview of everything you need to know in order to succeed on Kickstarter at the first time. You’ll need to do a lot of your own research after you read this. You’ll need to solve problems on your own. This guide is intended to help you get going when you’re not even sure where to start.

I’ve broken this guide into six sections

- The Kickstarter Mindset

- Preparing Your Game for Kickstarter

- Building an Audience for Kickstarter

- Campaigning on Kickstarter

- The Mathematics of Kickstarter

- Fulfilling Your Campaign

The Kickstarter Mindset

Kickstarter is not a magic money machine. A lot of people cling tight to the old myth that you can simply start a campaign with a good idea and get funded. After all, if a guy can get $55,492 for making potato salad, your artisanal board game is all but certain to get funded at like $8,000, right?

No. Let go of that idea. Trust me, it will save you some heartbreak.

Kickstarter is the last step in a long process. Last week, I wrote A Crash Course in Board Game Marketing & Promotion that goes into a lot more detail, which I strongly encourage you to read. I’ll go ahead and summarize my feelings on Kickstarter once more since this is so crucial to your success.

Kickstarter is near the end of the process.

Kickstarter only pushes people to take action. If no one is looking, if no one cares, and no one wants what you’re selling, Kickstarter won’t solve the problem. Kickstarter works because it is a time-limited campaign that takes place in a public venue which board gamers trust. Kickstarter is useful because it comes with a built-in stopwatch and because the name is bigger than Indiegogo or any other crowdfunding site. You have to make people know you exist before you start a Kickstarter. You have to make people care about your game and want your game or else you’ll wind up one of “14% of projects finished having never received a single pledge.”

I’m in a unique situation. I failed at Kickstarter my first time, spent six months building an audience and improving my game, and I was able to succeed the second time around. While I made cosmetic improvements to the campaign page and quality improvements to the game, the main difference – by far – was audience size.

How done is done?

Another thing you need to keep in mind about Kickstarter. Since you are asking for funds before you manufacture your game, your backers will need to wait a few months before they receive the game. That means it’s not quite a pre-order system, though it sometimes feels like it. You need to give your backers a little bit of room to influence your game. Your game needs to be 90 – 99% complete – enough to where backers know what they’re getting but not so much that they can’t influence you at all.

Please note that to get to 90% complete, you probably need to finish all or almost all your art before you go to Kickstarter. In fact, you probably need to do that before you get reviews of your game prior to the Kickstarter. You invariably have to compete with either mega-projects or at least very polished projects made by repeat campaigners. You cannot afford to go into Kickstarter with half a game.

On top of all this, Kickstarter is an environment which is always in flux. Keep an eye on changes and trends. Back 10 or 15 campaigns for a dollar so you can watch their behavior. Pay attention to successes and failures alike, since they can both teach you.

Preparing Your Game for Kickstarter

Understanding Kickstarter as an ecosystem helps, but I also want to prepare you for the actual project-related demands you will encounter, too. Before you even log onto the site with intention to start a campaign, you need to be working on marketing, promotion, and branding. Once again, I’d like to direct you to A Crash Course in Board Game Marketing & Promotion, since this makes or breaks creators. You want people to recognize your name and your game. You want them to care.

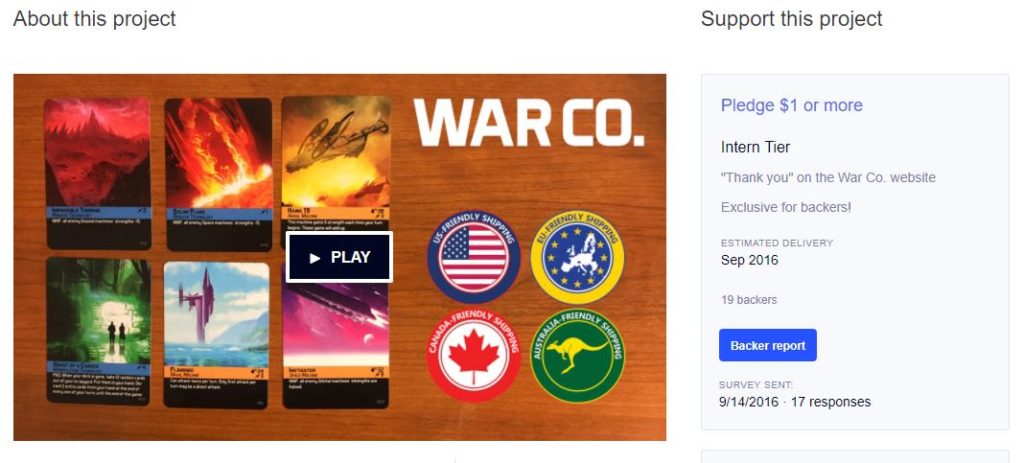

Since you’ll be bringing your own entourage, though, it makes sense to roll out the red carpet. The way you do this on Kickstarter is by making an absolutely gorgeous Kickstarter campaign page. You want it to also have very clear text that speaks to most of the reservations potential backers might have before spending their hard-earned cash on your dream. In short, no matter how new you are to the board game industry, you want polish. Funny enough, this is actually something I failed at a bit in the War Co. campaign, but I’m committed to teaching you how to do better even than me.

The best thing you can do is get reviews of your board game well in advance. In a later article of Start to Finish, I’ll tell you how to do that in detail. For now, just know that you should plan for 8-10 weeks of time for the review process to take place before you launch your campaign. Of course, before then, you’ll want a polished, fun, complete game to send out to reviewers.

A checklist for Kickstarter campaign pages

As for the campaign page itself, here are some guidelines for you. Use them as a checklist.

- Make sure you have a crystal clear, high-quality video that explains what your game is about and why it’s special. Keep it down to 2 minutes tops.

- Use lots of amazing photos.

- Have around 5 – 8 rewards. Ideally, have a $1 reward, a core reward, and something really special for high-dollar backers.

- Explain your game at the top.

- Get real photos of your game looking gorgeous and display them prominently.

- Share the rules or an abridged version of the rules with a link to the full rule book.

- Tell people exactly what’s in the box.

- Share your story.

- Tell people how far along you are and what’s left to do.

- Share pull quotes from glowing reviews, with links to the reviews themselves. Bonus points if they are big-name reviewers.

- Have a print-and-play or Tabletop Simulator demo ready and linked – or both!

- Make a detailed budget.

- Have a shipping section.

- Make sure you have customs-friendly shipping for Europe and the USA, at the very least!

- Have a detailed timeline.

- Have at least five compelling stretch goals ready to go.

- Be super honest in your mandatory Risks and Challenges section.

- Optimize, optimize, optimize. Read everything you can find on Kickstarter and pay attention to current trends. Tweak your campaign to fit well in the environment you’re currently in now.

Building an Audience for Kickstarter

While matters of marketing, promotion, and branding are best explained in A Crash Course in Board Game Marketing & Promotion, I’d like to point out a few types of marketing that are especially powerful for Kickstarter.

Mailing lists are often considered one of the strongest forms of online marketing. This is conventional wisdom that you can find repeated on a lot of websites, and indeed, email drives a lot of the traffic I get on this website. The magic of email is that lots of people tend to click on links that they see in there. If you’ve got a 5% click rate and 1,000 person list, then if you post a link to your Kickstarter, you are likely to get around 50 clicks. A good portion of those 50 will end up backing your campaign. That’s really powerful and you can build this long before your campaign.

Another incredibly powerful form of marketing for Kickstarter is social media. You can announce your campaign right as it launches, and you’re likely to get shared or retweeted. Granted, it takes months and years to build up a social media following, but there are lots of ways you can do it.

Mailing lists and social media can be used to sell practically any kind of product, but Kickstarter brings you some special opportunities. With board game Kickstarters, reviewers will often link to your campaign, bringing you a lot of traffic that way. This is yet another reason to solicit reviews well in advance.

Press Releases

You can also send press releases to websites such as Dice Tower and Tabletop Gaming Network. They will often include links to your Kickstarter on websites that people read for news. Every once in a while, people will organically share links from those websites in places like Reddit. If your game ends up being upvoted in a thread on Reddit, that puts you in a very good situation. Of course, Reddit is known for being hard to market to, so it’s especially important to send press releases to places that Redditors read so they’ll find your stuff on their own.

Media

There are tons of podcasts and blogs about board games, many of which are run by individuals like you and me. They’re often very open to collaboration and interviews. Try reaching out to some of them, even if they don’t have a very big audience. If you can find people with 10 or 15 regular fans, that means you’ll get a few more sales by merit of collaborating with them. As for the bloggers and podcasters themselves, they often are relieved to have some free content!

Lastly, look into Twitch streaming in the weeks before your campaign and during your campaign. If you make an online demo of your game through Tabletop Simulator, you can reach out to Twitch streamers on Twitter and ask to play a game with them online in front of a digital audience. It’s not hard to find streamers, either, they’re very abundant on Twitter. Twitch streaming is an excellent medium because even if just 10 or 20 people hang out in the lobby of the Twitch streamer and chat in the chat room, they’re often highly engaged. You can stream to an audience of 20 for three hours and walk away with $500 if it’s a good night.

Bringing it all together

Now I’ve spoken to the importance of “bringing your own entourage” before starting a campaign, but there is one exciting fresh thing that comes out of Kickstarter. The crowdfunding site tends to bring its own community, which can make 20 to 40% of your funding. Weirdly, and based only on my own and others’ anecdotes, it tends to pin itself to the amount of funding you raise elsewhere. This can be thought of as a sort of “Kickstarter magic” because a lot of people will see your game for the first time when you launch and they’ll say “hey, this person’s close to funding / already funded!” Then they’ll back you because, well, monkey see monkey do.

Campaigning on Kickstarter

Let’s fast forward to the future now. Say you’ve got an audience and a campaign page that is extraordinary. Let’s say you’ve chosen a launch date of Monday or Tuesday and your finger is hovering over the Launch Now button some time around 11 or 12 in the morning Eastern US time.

You’ve just launched. Now what? After waves of excitement, anxiety, and plain old blood-to-face flushing heat, here is what you can expect. You’ll probably encounter lots of questions and a handful of unclear things you need to fix. You should probably take the day off, perhaps even the week so you can fully commit to doing these two things as soon as they come to your attention.

Answering backer questions is very important. You’ll get comments and direct messages, so you’ll want to be courteous, polite, and clear in all your responses. You may even want to recruit your friends or business associates to field some of the questions if you expect an especially large audience.

It’s also a good idea to thank every backer via direct message as soon you can, even if they just back for a dollar. It’s a nice thing to do and people really appreciate it. It also makes them feel more comfortable coming to you with advice and constructive criticism.

After the big boom

In the next few weeks, once the initial boom dies down to a dull roar, you’ll have two primary areas to focus on before the big boom in the last 48-72 hours. These two areas are updates and stretch goals. The purpose of both of these is to keep momentum going.

You should regularly update the project with new information as time passes. While the purpose of issuing updates is to keep campaign momentum going through the slow parts, you should definitely only update the campaign when you have new information. Try to update the campaign twice per week during the campaign and every week or two after the campaign is complete until the project is fulfilled.

Stretch goals are really important to board game Kickstarters. You should have several planned out in advance and keep at least two visible at any given time. You can make more stretch goals visible as you go on, or you can show all the ones you have planned from the start. It’s your choice – this is something silly a lot of people tend to argue about. I haven’t found either option to be notably more effective.

A good idea for stretch goals would be component upgrades. You don’t want to have 80% of your game going out at the funding level and sell the additional 20% in 10 2% increments. I like using component upgrades as stretch goals because adding them benefits all players – the ones who back you during the campaign and people who buy your game later. They also happen to be something everybody can rally around because thicker cards, nicer boards, and other tactile stuff like that isn’t needed but sure is appreciated.

The Mathematics of Kickstarter

When you go into Kickstarter, you actually need to have a goal that’s substantially higher than manufacturing costs. In fact, if you take your manufacturing cost and divide by 60%, that will give you a figure that makes for a good goal. By assuming that only 40% of your funds raised go toward manufacturing, you have plenty of money left over to cover Kickstarter fees, shipping, sales tax, returns, damages, and unexpected costs. It’s important to remember this is only a ballpark estimate. You must do your own math before launching a campaign.

Kickstarter will take about 8-10% of your funds raised no matter how much you get. Shipping is determined by how much your product shipping costs relative to reward levels, how far away your backers are, and your shipping company or companies.

If you’re an American, any products shipped to people within your state may be subject to sales tax. If you import goods into your state, they may also be subject to use tax. You need to look all this up on your state and local Department of Revenue sites. If you’re not a resident of the USA, you’ll need to do additional research since that’s out of my area of expertise.

Financial Planning

Bear in mind that Kickstarter revenues are considered income. If your Kickstarter revenues exceed your project costs minus the value of inventory, you may have to pay income tax on your Kickstarter funding as well. Plan around this. The last thing you want to do is successfully raise funds in October 2018, spend the money in November 2018, and get caught in a cash crisis in April 2019 because the IRS has taken an interest in your success.

Plan around multiple scenarios, such as:

- Failing catastrohpically

- Failing, but just barely

- Barely making it

- Raising twice your goal

- Making several times your goal

- Reaching tens of times your goal

All of these could happen and you need detailed financial plans around each of them.

Fulfilling Your Campaign

I’ll cover this in more detail next week since this is a novel unto itself. As many as 84% of Kickstarter projects fulfill rewards late, which is a testament to just how hard this is to get right. There are two broad ways that you can fulfill your project. You can fulfill it yourself or you can fulfill it through third parties such as Games Quest or Snakes & Lattes.

You can only realistically fulfill a couple hundred copies of your game by yourself, and even then, you should not self-fulfill rewards that are going to other countries. It’s way too easy to screw up. I strongly recommend that you start searching for reliable third party companies to fulfill your inventory. Pay attention to what high profile campaigns are using these days. Watch for good and bad signs. In general, your two biggest concerns should be how well the company communicates with you and how much it costs to fulfill.

Again, I’ll provide more information this coming week since this is a real rabbit hole.

Kickstarter is a place of tremendous opportunity and equally tremendous peril. As a community, it has complex norms that you have to learn before you jump in. I hope this article helped demystify this behemoth of a website. Use this guide as a rough overview. Keep your eyes and ears open, ask questions, experiment, and learn as you go.

If you have any questions or comments, I encourage you to comment below 🙂