How to Play-Test the Mechanics of Your Board Game

Board game development is a very individual process. Every single developer has different methods for creating their games. This article is the fourth of a 19-part suite on board game design and development.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

This suite is based on the Five Levels of Communication through Game Development, my own personal board game development philosophy. However, I’ve brought in Jesse Bergman, the lead designer of Battle for Sularia so that you can get two viewpoints instead of just one. We’re picking up where we left off last week with How to Design the Mechanics of Your Board Game, so read that if you haven’t had the chance yet. Today, we’ll be focusing on testing game mechanics after you design them.

A quick recap: game mechanics are how we bring the core engine of a game to life. Jesse and I will explain further. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our direct messages on Discord.

This guide comes in three parts:

- How do you test game mechanics?

- When do you focus on one mechanic?

- When do you drop, refine, or keep a mechanic?

How do you test game mechanics?

Brandon: How do you test game mechanics?

Jesse: I think it depends on various stages of the development process. When I first complete my rapid prototype, I call this Phase 1. Inside of Phase 1 I test the core gameplay loop. I do this solo with no one else around. I want to make sure that the game is working first before I share it with others. At this point, I do very little to tweak emerging behavior. I’m mainly interested in if the game can reach a victory condition and how long it takes.

Jesse: During Phase 2 I begin showing the game to other players that are interested. In this phase, I’m watching for dominant strategies and emerging player behavior. This is where I start to dive into balancing mechanical choices with regards to elements of the game, like spaces on the board for worker placement or card abilities in a card game.

Jesse: Phase 3 is where I really fine tune a game. During Phase 2, I try to get the game closer to about 90% complete from a development standpoint. Then during Phase 3 I do any final adjustments to the game based on additional tests that may show new or different imbalance issues.

Jesse: Ultimately, I ensure that each play-test session has a very specific purpose. If I’m worried about a particular player strategy I will ask one of the play-testers to focus their strategy on that. The goal being to see if the strategy is actually dominant or if my hypothesis is unfounded.

Jesse: During Phase 3 I also begin looking for blind play-testers. This process is arguably the most difficult as there are simply not that many blind testers out there and available to give you adequate feedback.

Jesse: We want to use blind feedback to gauge interest in the game because it’s more true to how the public will likely respond. In my experience, it’s just not enough people to really know.

Jesse: After Phase 3, the game goes to Phase 4 where we begin putting final illustrations and game elements into it. At this stage we are no longer testing but now demoing the product anywhere and everywhere.

Jesse: How much do we differ from your process?

Brandon: This is actually really close to my process.

Brandon: With Highways & Byways, my stages were called State Route, Highway, and Interstate. So my versioning would go State Route 1, 2, 3… then Highway 1, 2, 3… then Interstate 1, 2, 3…

State Route: Left

Highway: Middle

Interstate: Right

Brandon: State Route is a mix of your Phase 1 and Phase 2. During the earliest stages, I self-tested just to make sure the core engine functioned. Then I picked mechanics, trying each one – one at a time – to see if they worked. I tested with my immediate family at this stage.

Brandon: Highway was equivalent to Phase 3. Start fine tuning mechanics (once I figured out what the main ones are).

Brandon: I started doing what I call “single-blind testing” in the Discord server. I’d find people, have them read the rules, and teach me how to play. By actively participating but not revealing everything, I got some of the benefits of blind play-testing before I was ready for blind play-testing.

Brandon: Interstate is equivalent to Phase 4 – illustrations, refinements, and tweaking. The only difference is I blind play-test while waiting on art.

Jesse: The single blind play-testing model is interesting to me. So if a player teaches you incorrectly does that mean the rules are problematic or the game?

Brandon: Single-blind testing lets you catch confusing stuff on the rules, fiddly components, unclear wording, etc. I spend half my time taking notes in those sorts of tests because they help you catch far more details than a full blind tester would capture on a survey form. Plus you can get a feel for their raw emotions and not just how they frame their raw emotions afterward.

Brandon: You can do all this by observing from the background, yes. But when you’re not quite ready for fully blind play-testing, I don’t think it hurts any and people really like playing with the creator of the game.

When do you focus on one mechanic?

Brandon: What do you do when you need to focus on one mechanic?

Jesse: When we were developing the upcoming Reign of Terror expansion for Sularia this last year we introduced a brand new ability in the game. This ability was, in my mind, being underutilized by the core test groups in favor of their more familiar paths to victory.

Jesse: This mechanic was called Anarchy. It would destroy sites once you had created enough anarchy at the site in the game. Destroying sites deals damage and gets the player closer to victory. Players’ perceptions were that this was simply not as fast as attacking and dealing damage the normal way.

Jesse: We as developers were wary of one of two things.

- The mechanic was subpar and, as a bookend to the faction, would have a poor response in the wild.

- The mechanic was very strong, but misunderstood. That would lead to it emerging in such a way that it would create a negative player experience after it was discovered.

Jesse: Our response was to have a fixed amount of testers find competitive decks with the mechanic. Our findings from those sessions proved that #2 above was confirmed as real. The deck, after a few weeks of tweaking, became so dominant that it forced a rebalance of it and its sister mechanic in another faction.

Jesse: That sort of response isn’t found if, as a developer, we just let our players play and see what happens.

Brandon: What you experienced with the Anarchy mechanic is really important. I find that sometimes you either have to test a mechanic yourself or tell others directly to do it.

Brandon: I’ve flagged mechanics for “potential broken-ness” with intention to test them that way. I usually do this any time I have even the slightest hint that a mechanic could lead to runaway effects OR if I don’t understand what will happen yet.

When do you drop, refine, or keep a mechanic?

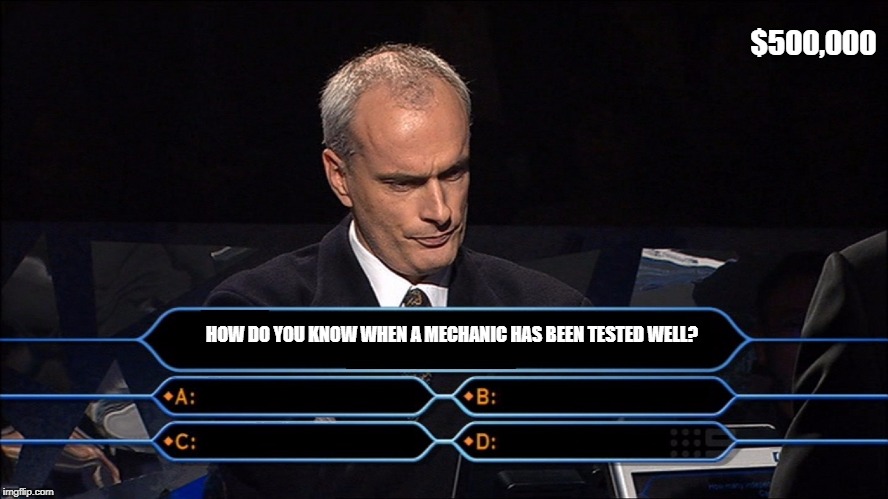

Brandon: How do you know when a mechanic has been tested well? How do you know when to keep a mechanic as-is, refine it more, or drop it entirely?

Jesse: That really is the $500,000 question. A mechanic can be tweaked to the point that it removes the fun in it. I believe that simple mechanical tweaks can be the difference between your game just being okay or being absolutely awesome.

Jesse: I think you know when a mechanic is done, when the play testers don’t complain about it and even potentially compliment it. When a mechanic is so seamless with the player that it just feels natural, you have a winner. Otherwise, it can be jarring and off-putting.

Jesse: In Sularia, we watched win/loss ratio along with details regarding things such as turn with first meaningful play to determine if the mechanic is contributing to the issue or if some other factor is. Mark Rosewater (head designer of Magic the Gathering) said in one of his drive-to-work podcasts, and I’m paraphrasing here “when a color or deck is acting up, it’s very easy to point the finger at an obvious card or mechanic, when in reality there is something much deeper causing the issue.”

Jesse: That particular line resonated the most for me, because we’ve seen it countless times now as we’ve developed a card game. I know that the advice is good regardless of what type of game a player is working on. In order to purely abandon a mechanic, data from play-test sessions has to substantiate the reason. If you have a mechanic that many players hate, but it’s integral the game, should you abandon the mechanic, the game, or what?

Jesse: I also think it’s very important to not throw the baby out with the bath water and keep a very open mind to how your game can evolve when you get out of the way and let it have its own life.

Brandon: Seamless is really the watch word there. If you need a bunch of rules to regulate mechanics, that’s usually not a good sign – a deeper issue like Mark Rosewater suggests.

Brandon: If it feels seamless and adds depth from the get-go, that’s great. Keep it and refine a bit. If it’s awful from the start, drop it.

Brandon: If you can’t get a mechanic to work after three or four versions, that’s when I think it’s time to let it go. I actually did this with War Co. back when it had a traditional life system like Magic.

Jesse: Yeah we dropped a mechanic from the upcoming Protoan line called Armor. The intention was that when a Protoan with Armor would die it would lose its armor token but remain in play.

Jesse: We could never get the balance on Armor cards quite right. They would either be to underwhelming or insanely powerful. The mechanic was abandoned and the faction redesigned to Virus, which will be found in the final release.

Brandon: Did you find that swapping it out was a lot easier than fooling with refinements over and over?

Jesse: Not necessarily easier, but the faction is way more interesting now.

Jesse: Getting Virus to function and behave properly took refinement but the game is better overall because of it.

Brandon: I find my games often make substantial leaps forward when I drop a mechanic that’s dragging them down.

Brandon: Thank you very much for working with me on this article!

Jesse: Thank you, Brandon! I really enjoyed this, I hope we can work together in the future.

As you can tell, creating and testing game mechanics is a nonlinear process. By sharing our individual methods, Jesse and I hope to be able to help you create elegant mechanics for your tabletop games.

In next week’s article, I’ll talk about how you make rules for your game to help you regulate the excesses of your mechanics. In the mean time, please leave your questions and comments below 🙂