How to Tell Great Stories Through Board Games

Board game development is a very individual process. Every single developer has different methods for creating their games. This article is the seventh of a 19-part suite on board game design and development.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

This suite is based on the Five Levels of Communication through Game Development, my own personal board game development philosophy. However, I’ve brought in Dylan Cromwell, the lead designer of Seize the Bean so that you can get two viewpoints instead of just one.

For this and the article that follows, we’re going to focus on what I call internal narrative. It is true that games speak to players through gameplay – the core engine, mechanics, and rules. However, when people think of storytelling in games, they think of theme, story, art, components, and even box design. The internal narrative covers everything about the game itself as a complete product minus the gameplay. That’s what we’re talking about today.

This guide comes in four parts:

- Who is Dylan and what is Seize the Bean?

- Why is storytelling important?

- How can you tell stories through games?

- How do you make stories match their games?

Who is Dylan and what is Seize the Bean?

Brandon: Thank you very much for agreeing to help with this post!

Brandon: Tell me a little about yourself and your project, Seize the Bean.

Dylan: I’m a long time artist and creative person – started out drawing and blowing glass. I’ve always had games in my life since being a dungeon master in D&D as a child. As I grew, I got more into technology and found myself doing mostly programming jobs.

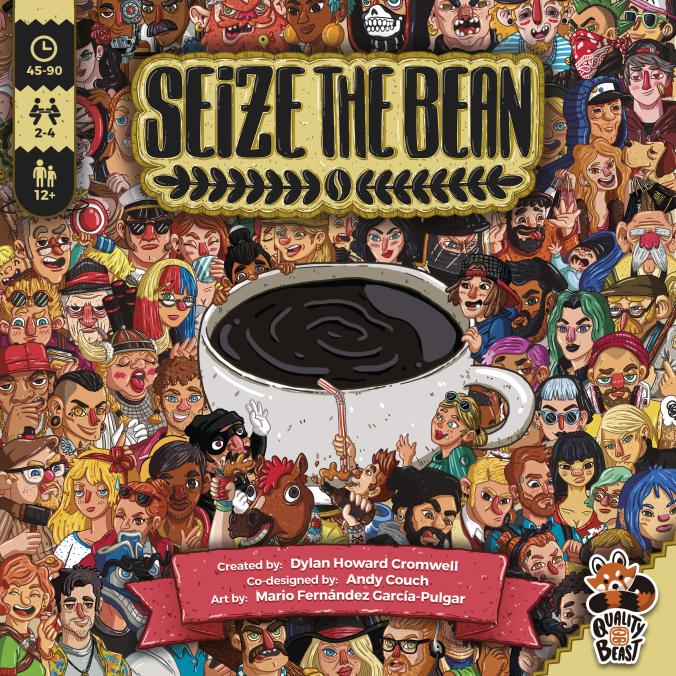

Dylan: Recently I’ve learned to grow and manage great teams as well. I’ve just had my first child (a daughter!), so I’ve time off of work. Whilst spending it with my family, I’m also utilizing it to attempt to launch my own games publishing company, Quality Beast. Our first project scheduled for release is Seize the Bean, a comical, super thematic deck-builder based on our HQ city, Berlin.

Dylan: In Seize the Bean, players take the role of pretentious baristas (no offense!) who believe they can do everything better than their boss. They quit their job and grab their measly savings to open their own hot café in the diverse city of Berlin. The only problem is that all their friends (also pretentious baristas) have done the same thing!

Dylan: It was our intention from the beginning to create a silly, tongue-in-cheek game that acted as a window into the diverse and distinct social archetypes of Berlin: hipsters, tourists, artists, start-up employees, unemployed expatriates, street freaks, tech nerds, families, fashionistas, society rebels, and more. We knew we wanted to allow players to attract certain types but also wanted that players would need to manage who came and how they were served. Would a hipster like it if you also served tourists?

Dylan: The trick about the game and the theme is that no one agrees on what makes things the best. Is it hype? Coffee quality? Social dynamics? A quiet place to work alone? We wanted the game to allow a variety of strategies to be victorious, thus allowing the players themselves to show their own diversity. We wanted some people to play it with careful resource management whilst others treated it like a push your luck game of scarcity.

Dylan: This was our challenge in trying to flesh out appropriate mechanics for Seize the Bean’s wild and almost untame-able theme.

Brandon: That’s an exciting theme! It seems we’re both working to capture physical locations through gameplay, so this resonates with me.

Brandon: Berlin, in particular, is one of the most culturally eclectic cities in the world. The coffee shop – real or in game – provides a common ground for all these different sorts of people to gather and mingle.

Brandon: Because we are all, of course, addicted to caffeine 😛

Why is storytelling important?

Brandon: A lot of people who first get into board gaming are surprised how rich and immersive their worlds can be. Why do you think storytelling is important in board gaming?

Dylan: I’ll try to answer that both personally and professionally.

Dylan: For me personally, I must admit I’ve heard people (especially those in my team) refer to me as “the theme guy.” I’ll see a piece of art or hear an ancient myth and – boom – I’m inspired. My design visualizations always have a rich thematic beginning, even if that theme is abstract. That story is really crucial to me because it pulls me in. Sure, once I’m in, abstract strategy is fine and I can get really deeply focused on it (in fact our next release will be an abstract strategy game), but having some layer of make-believe lets me fully enter that world.

Dylan: Chess is such a fantastic example: it’s really a geometric puzzle. But the pieces have such honor, prestige, and allure to them that it gives way to a rich and complex history even without having any formal story at all. Almost no one I know begins chess with a story of “you are a king / queen at war.”

Dylan: On a professional level, whilst I am new to the board game industry, I’ve found that art and theme are the major components that can bring people in without having heard anything about the gameplay. I don’t ever want to proclaim this is more important than mechanics; it certainly is not. I’ve found that the majority of players who may be attracted by art and story are just as easily pushed away if the mechanics aren’t fun and don’t back up that story that’s been told.

Dylan: In fact, we faced this dilemma with version two of Seize the Bean, where the game mechanics were becoming some sort of grindy euro engine builder which completely betrayed the story that the art and theme was selling to the players. I think not everyone needs this, but on some level a lot of players appreciate the presence of a rich and thought-out theme and art basis upon which the mechanics lay, because it allows them to dive more deeply into the experience. It gives them a universe to explore; it brings what would otherwise be pretty dry mechanics to life.

Brandon: “Theme guy” has been reading ancient texts again and claiming it’s for work…

Brandon: On some level, humanity is built to see stories no matter where we look or whether they’re really there or not. You can even see this in chess or abstract euros simply through the actions you perform within the game. Now you mention earlier that sometimes theme and mechanics can clash and work against players’ expectations in a negative way. I’ve actually touched on this before. I use the phrase theme-mechanic unity to describe when the theme and the gameplay perfectly line up.

Brandon: Failing to achieve theme-mechanic unity can feel really off-putting, especially in modern gaming.

How can you tell stories through games?

Brandon: All this said, what tools do we have at our disposal to tell stories through games?

Dylan: The most obvious is art. The second is language. These are two I’ve found come most naturally to me. Especially with English – thankfully a super blurry language to begin with – there is a lot of room to work around the theme, finding new names for things that might be more convincing and thus more immersive for the players.

Dylan: But art and language can only get you so far. Discovering physical or mental actions that players embrace in the game helps a lot to deliver the story; not just because they may fit the theme, but because the players do these things themselves. In essence: they drive the story.

Dylan: In Seize the Bean, for example, we knew that the player had to have a way of stylizing or building their café so that it attracted the type of customers they were going after. It took a lot of variations until we found the right approach, but something a simple as installing a tourist upgrade (like free Berlin city maps) gives the player the ability to now take a tourist customer card during an open draft. This really helps to put the player in the driver’s seat of their own story within the game’s universe. What we found was this went beyond our expectations of a pre-established story: it allowed players to create stories we hadn’t even thought of yet.

Brandon: Art, language, and mechanics sell the story in a big way.

Brandon: I’d say that components and the physical or social behaviors you are compelled to perform should be included as well. A really simple example from my own work is that Highways & Byways is about travel, so all the Travel Markers (placed to show where you’ll be traveling), have little GPS symbols on them.

Dylan: You’re right! How can I forget: Seize the Bean’s components fuel the theme for almost all our players. We’ve created our own 3D printed coffee beans (literally modeled after a real coffee bean), miniature milk cartons and even super realistic sugar cubes. Not only do we provide these in the game, but there’s a fun and light-hearted scooping mechanism in which players get a variable amount of beans with each go. That and some small, silly good and bad review tokens with funny statements on them all work together to really bring out the theme.

How do you make stories match their games?

Brandon: How do you make sure the story you’re telling is consistent with the gameplay?

Dylan: That’s a hard one. We discovered that our story was more about humor, which is typically a lightweight feeling, so the game shouldn’t feel overly heavy or go on too long. We also noted it was bringing in a crowd of very diverse gamers, even groups that had a diverse range of game experience and different approaches to the learning curve. This meant that brutal penalties or lack of rubber-banding were a really bad thing in our game.

Dylan: Early on, our story and mechanics allowed shops to go out of business, literally ejecting players from the game. It became obvious that while this could be part of the story, it betrayed the ideas of fun and humor and thus didn’t fit the game’s true ethos. I think this is important for creators to remember: your story is how you write it and it can change. Watch and listen to your players and how they react, they are going to be your compass, guiding you back on track to keep your story and gameplay consistent.

Dylan: I also think you should talk to your team and ask again and again “what is our game about? How should it play? What is its weight? Who are its target players?”

Dylan: These question are super easy to only ask once and forget or even overlook completely. But they help set your goal. It took us until the third version of Seize the Bean to finally say “this is not a grindy engine-builder euro, it’s a kennerspiel, yes, but one that’s quick to explain and not to long to play”.

Editor Note: Kennerspiel translates to “connoisseur/expert game.”

Brandon: I agree that humor and game length are connected tightly. Part of the magic of good jokes is that they’re gone just as soon as you process them. You can’t overstay your welcome! In games, that means keeping humorous ones under an hour (usually…always play-test this stuff). Same thing with game weight and learning curve.

Brandon: It sounds like you had to experiment a lot before you found what you ultimately wanted Seize the Bean to be about. This is something that happens in game design a lot.

Brandon: To share some examples from my own experiences about making gameplay and storytelling consistent…

Brandon: War Co. is about scavenging the remnants of a very, very old war and using them to fight in an endless cycle of retaliation. Such a waste of human potential! You see this reflected in the fact that the entire game is about reducing your enemies’ supplies to nothing. You feel the effects of scarcity because you always have to throw out one of your own cards at the end of the turn, too. It’s a harsh, unforgiving game (and a lot of people are surprisingly into that!)

Brandon: Highways & Byways is about constantly being on the move, a narrative borrowed from some pretty extreme road trips I’ve taken (like 5,000 miles in 9 days). That’s what the whole game is about – moving physically on the board and travelling real roads. Every turn you have to deal will something that happens to you. You try to plan for the future. I’m relentless about keeping the underlying story consistent in the way it plays, looks, and feels.

Brandon: So let’s say you’ve done some play-tests and you’re ready to start ordering art and making physical components. How do you make sure that your art and components are consistent with your storytelling?

Dylan: Art direction and component choices are a tough piece of the puzzle. Finding the right artist is key. It’s better that you align with someone’s natural instinct and style so they are at their most comfortable. There are some extremely professional and highly talented artists and graphic designers who can create a wide array of styles but mostly people already have a vibe and matching this to your game – and what your audience is going to expect and like – is pretty key.

Dylan: Once you’ve done that, making sure to set up a good working arrangement with your artist and/or graphic designer is also very important. People work best when things are clear and fair for all. Beyond that, making sure to supply them enough info about that game up front is also very important; even better if they’re able to play the game and get a feel for it. Not a single creative person I’ve ever encountered wants to be told exactly what to do, so it’s a good idea to explain how their work should feel in the end, but not precisely outline what it should look like; give their creativity space to grow and stretch your story. Many artists are fantastic storytellers and if you let them into your universe they’ll likely expand it beyond your expectations.

Brandon: Finding the right people is so, so important.

Brandon: If you do that you can give them a paragraph or two for each piece. Otherwise, let them run with it. The results then wind up that much better because you’re not nailing art to a spec document, though documents are important.

Dylan: For components, the trick in the end is always going to be the price. Board games aren’t easy to manufacture or sell unless you’ve got a lot of funding up front, ready to spend, and a lot of confidence on the back side that your game will sell enough to replenish the investment. We’re lucky enough at Quality Beast to have team members who can 3D model and 3D print so we’re able to experiment in those areas.

Dylan: On a more simple level, though, thinking about how each component represents something in your game world is a good exercise. Does this card allow the players’ imaginations to run wild? If not, ask yourself what else could it be that would further the game’s immersive environment. We’ve gotten away in a lot of areas of Seize the Bean by converting things like “victory points” to “good reviews” but had a tough time getting the player board to be both functional and represent a café environment accurately!

Brandon: Components are hard. You’re right that especially for the newer designers, you need to find what’s available and work with that when you can. If you customize, you better make it really, really count.

Brandon: If you can’t do custom components, I’d argue the next best thing is using them creatively. I’m turning tarot cards into postcards for Byways. If memory serves, Colt Express turns interlocking pieces into a train.

Dylan: Sometimes it’s even about removal of components completely. Often we designers try to cram too much into one game, constantly demanding that it fit our original vision.

Brandon: Yes, absolutely. And that’s something you have to train yourself out of. Creation requires reduction.

Dylan: We had this issue with “coffee blend” cards, trying to make Seize the Bean into a dual-deck-builder (customers going into one deck, blend cards going into another). I’m very happy we wised up and scrapped that idea. It was just too much going into a game that ultimately wanted to be about customers not coffee itself.

Dylan: So, in summary, getting the art and components to match the story is also about letting go. The same could be said for mechanics too, I think.

Brandon: Similarly, Byways has left behind an impound yard of abandoned mechanics. War Co. had 500 cards at first and 200 of them never made the cut.

Dylan: Hahaha, yes, I know that exact process. “Kill your darlings” I think some have called it. A typical writing technique.

Brandon: I’ve heard it called the delightfully morbid “drowning puppies”

Brandon: Which…god…what an awful and vivid metaphor

Dylan: Ouch. That’s a game whose story I wouldn’t like to see fleshed out in component, art nor mechanics. I’ll say that much!

Brandon: So next week, we’ll talk less about what storytelling is and more about how to do it right. Stay tuned, everybody!

Telling stories is one of the most essentially human instincts. Whether or not we mean to, we tell stories through games. It’s best to embrace storytelling no matter how thematic your game is and perfect its tone. Through art, physical components, and clever use of language, board games can transcend their parts and become rich experiences.

In next week’s article, Dylan and I will continue to discuss storytelling in games. We will focus on testing our stories instead of simply creating them. For now, please leave your questions and comments about storytelling in games below 🙂