How to Make the Perfect Board Game Rule Book

Board game development is a very individual process. Every single developer has different methods for creating their games. This article is the thirteenth of a 19-part suite on board game design and development. This week, I want to zero in on the subject of making the perfect board game rule book. To help understand this subject, I’ve brought in Chad of the Writegamers.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

This guide comes in seven parts:

- Who is Chad?

- Why writing rules is different than other kinds of writing

- How to structure a rule book

- Making rule books clear and concise

- Your player’s first experience and your rule book

- Dealing with rule book skimmers

- Parting advice

Below is a transcript of our conversation over Discord DMs. It has been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

Who is Chad?

Brandon: Tell me a little about yourself and your projects.

Chad: I’m an entrepreneurial sort; I’ve spent my life building experience in a variety of fields and industries to keep things fresh…starting in my teens with profitable web and Teamspeak hosting. Right now I work from home (the dream, right?) for a cloud consulting firm leading their application development resources. I also work with indie dev companies on a more casual level discussing challenges, goals and brainstorming solutions. On a more personal level, I publish an episodic webcomic for free, and paid novels (with periodic studio grade music to go with them) to market; currently my children’s book and my wife’s fantasy novels and children’s books.

Chad: The goal really is to make the Writegamers a platform for bringing experience and support to other startups – we already live in a future where everyone can create their own story. I want to help them succeed at telling it well.

Brandon: It’s fantastic that you’ve been able to succeed with a business you started in your teens!

Brandon: Both in consulting and in creating books, you’ve done quite a bit of writing. Spec docs, business rules, literature for a general audience and for children as well.

Why writing rules is different than other kinds of writing

Brandon: How does writing a game’s rule book differ from other forms of writing like blogging or literary writing?

Chad: With blogging, the content often comes across in an informal, personal tone. One can use slang and speak a little more freely – thoughts can diverge, merge, and take sideways jumps because the speaker is conveying what’s on their mind. The message is their own.

Chad: On the other hand, literary writing is storytelling through prose; the rules are quite different. The writer must create a world and entrap the reader so they can become immersed. The message must speak to a variety of people, so that ideally, there’s something for nearly any audience if they read long enough. The sentence structure must convey emotion and meaning on a personal level for the characters involved. However, typically in both formats, the tone and structure are consistent throughout the material.

Chad: With a rule book, the format is often more formal and factual but I believe it can have fluidity in terms of its structure. Specific rules/information may be conveyed in bullet points and/or through specific technical paragraphs. There may even be some storytelling to convey the reason or meaning behind a particular series rules and mechanics.

Chad: The reader must have an unequivocal understanding of what the rule means and why it’s important. However, it cannot read like an encyclopedia all the way through! It must be memorable and keep the reader’s attention so they can connect to it. I believe it can be conversational and engage the reader from section to section – with a block for the actual specifics in plain, clear writing.

Brandon: I definitely agree with that. You want to strike a balance between being specific and deliberate, but also human and approachable when writing rule books. They’re more formally constructed than blog posts and I’d argue even the prose you would see in literature.

How to structure a rule book

Brandon: With that in mind, what is the purpose of a rule book? What is the ideal structure of a rule book?

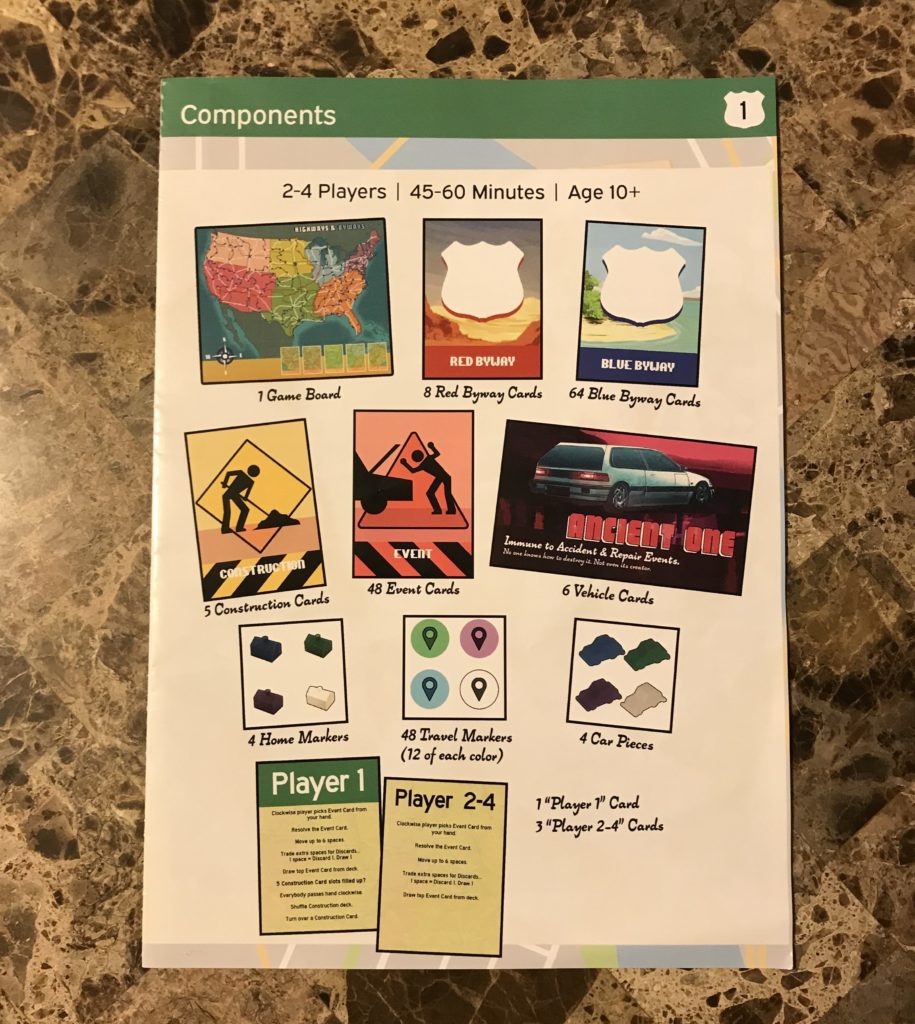

Chad: The rule book serves as a guide to teach new players and to act as a quick reference for experienced players. Even for the game designer, it’s easy to forget your own rules for a living, breathing project! Typically, the rule book has an introduction/overview, components list, setup instructions, gameplay, end game rules, and appendix. It isn’t limited to this, though. To make a game truly unique and engaging, a writer has room to play!

Chad: This is where hybrid writing comes into play. The introduction recaps the background story and thematically sets the tone for the game. Why are we here? Why is it important? This is conversational storytelling and there is freedom to explore.

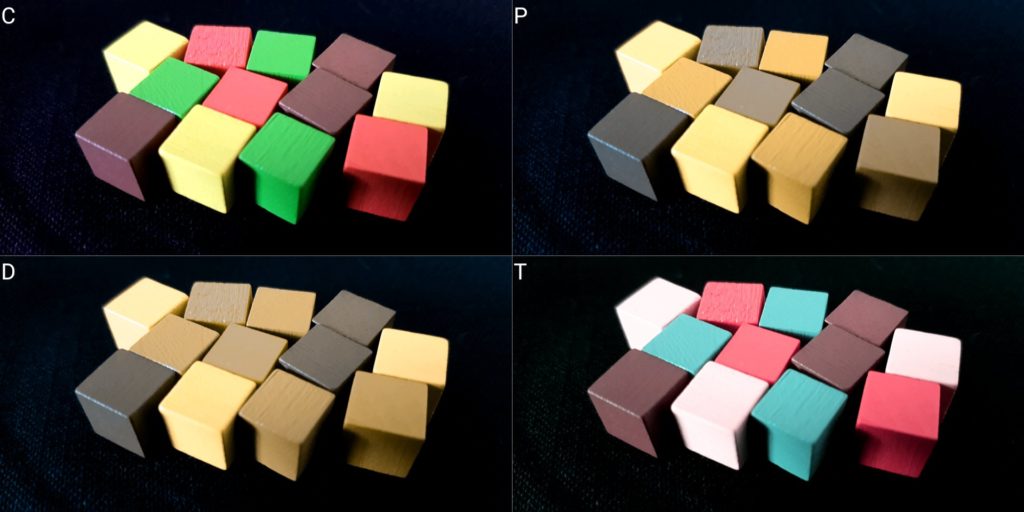

Chad: The components, setup, gameplay sections, and appendices should be in unambiguous, clear language. The components should simply and plainly list which items in the box are required to play. The setup instructions may include diagrams explaining how the board should be laid out. With gameplay rule writing, it’s important not to diverge into edge cases and one-off situations. The gameplay section should focus on round mechanics. How does each player complete and round and what must happen? If special events occur, refer players to the appendix.

Chad: This ensures the guide is clean and easy to read for new players and doesn’t require experienced players to run around trying to find information. Similarly, the endgame section must explicitly define what constitutes as an endgame and refer players to the appropriate appendix. The appendix is the encyclopedia of the game. Is there an edge case? One-off conditions, special events? Icon glossary and card definitions? Put it here…don’t clutter the gameplay mechanics.

Brandon: A handful of best practices come to mind right now. I’m a fan of starting with the components list, objectives, and overview…in that order. The components list helps by letting people know immediately what everything is called, then you can launch into the purpose and the basic concepts of the game. After that, I agree, it does get a little fuzzy. Clarity and concision become the most important values, and how you meet those goals is up to your tastes and those of your play-testers.

Brandon: I agree on keeping an appendix, too, I feel like that should be more common in games. Just about every game will have some bizarro edge case/corner case come up. And if you get too big of an appendix, that’s a sign you need to do some redesign. So in that way, it also acts as a canary in the coal mine for bad game design.

Making rule books clear and concise

Brandon: How do we make rule books both clear and concise?

Chad: The first thing I’d want to do is make sure I can actually play and understand what’s going on.

Chad: In terms of making the rules clear and concise, I think it’s useful to have a group of beta readers with different backgrounds, skills, and traits. As well, having people in different countries with different cultures to ensure you’re communicating clearly with them and not using an offensive stereotype by accident. This could be done through a Discord chat, Reddit, or social media. Don’t just give them the book and take their advice right off the bat – vet them, and find common trends among your readers. Don’t try to fix one-off issues unless you also see a problem and have a resolution. This can be democratized with a summary of proposed changes that can be shared with the group.

Chad: It’s important that the readers consist of both experienced and inexperienced members of the community, and even other creators. This provides a three-pronged approach to getting balanced feedback on the writing. This process begins with the first draft – write your thoughts down and format them generally how you’d like them to be read in the final product, then ship it off to get outside input.

Chad: We can write, edit, and review ourselves all we want, and we’re our own greatest critic – but we’re creating for an audience that spans the world and I believe that outside feedback is paramount in this case.

Brandon: The more readers you have, the better. I think it also helps to get a mix of different writers like bloggers and technical writers. It’s also a big bonus to get readers for whom English is their second language. This is a very iterative process.

Brandon: I think it’s important to realize that the way you structure your guide and the way you share information will prime players’ first game experiences.

Brandon: People tend to judge a game by their first experience – fairly or unfairly. The rules play a big part in that.

Your player’s first experience and your rule book

Brandon: How can we make rule books that prime game experiences?

Chad: I think a big part of it is structure and formatting, along with the actual quality of writing. The writer needs to put themselves in the shoes of a theoretical new player and think “If this was NOT my game, what do I expect to be able to succeed and enjoy my first experience” – and similarly, approach each review and draft of the final book with the same “fresh” perspective. Read it through the eyes of another audience member and see where something doesn’t feel right or doesn’t make sense.

Chad: The key, I think, is to avoid droning on or diving into abstract lore. Make it bullet point or keep the paragraphs short so it’s COMPLETELY clear what needs to be done. Avoid overly long sentences and repetition and immediately get to the heart of the matter. Use a clear, non-script font that is easy on the eyes. Whatever the message, I should read “point the glowing red end at the other person and press the button,” not “in the name of darkness, cast thou staff upon that villainous opponent and use the unholy rune stone while making three turns on your heel!” – that’s the backstory.

Brandon: It also helps to make the important stuff the first sentence of a paragraph or the first paragraph of a section. Images help.

Brandon: Basically prioritize very, very clearly what info needs to go to that theoretical new player. Then hammer that home.

Brandon: (It helps if your mechanics can gracefully degrade when rules are skipped, but that’s a whole other lesson.)

Dealing with rule book skimmers

Brandon: What do you do about players who jump right in after only skimming the rules?

Brandon: Or, for that matter, having the rules read partially to them by the gaming group’s leader.

Chad: As you noted, the important things have to be shown first! Players who skim and jump in will start “flailing” around in the pool otherwise. They have no idea what they’re doing and have to keep going back to the guide or miss important and fun mechanics by improvising. Similarly, by only having the rules partially read to them – you’ve now got a group going off the cuff without a plan. What happens then? The rules are given ad-hoc and someone gets frustrated because they couldn’t plan or strategize?

Chad: Shorter is better, not everyone has the patience or inclination to read an overly long manual. In this sense, it might also be valuable to have a quick cheat sheet of how to play the round with page references for further details. It keeps it short but allows players to quickly find their way if they have to get clarification on a specific line item.

Brandon: Reference cards go a long way. Even an eight-page rule book with big text is usually too long to get the full read. That’s why it’s very important to put the most important points in highly skimmable spots: the first sentence of the paragraph, bold font, in an illustration, etc.

Parting Advice

Brandon: One last question.

Brandon: As a gamer and as a writer, do you have any last parting advice for game developers?

Chad: I really enjoy complex challenges and innovative ideas in games, but it’s not for everyone. It can be easy to say “I really want to do something really cool” for the first game and immediately take the brand out of reach of any future audience. I’d recommend a compromise during your first project to ensure the player is met halfway. As well, you learn a LOT from your failures so don’t be afraid to fail – and to go back and “redo” a part of the project because you’ve learned something new that increases the polish on the final product.

Chad: In terms of writing a rule book, this is important because odds are you’ll start with a vision and have to scrap and restart a few times before you find that balance where you feel “this is mine and I’m proud of it”, and the audience picks it up and says “this is honestly one of the best rule books I’ve ever read.”

Chad: Always, it’s important to have fun and play – people can sense when heart and passion have been put into a project.

Brandon: Getting to any vision that’s worthwhile usually takes a ton of iteration and experimentation. Right there with you on that.

Brandon: Thank you very much, I can’t wait to share all this on the blog!

Creating the perfect board game rule book can be a balancing act. You want to give players a good first game experience through clear, concise, easy-to-understand rules. At the same time, you must cover all the important housekeeping tasks that make your game tick. It falls in a strange place where prose, technical writing, and marketing copy overlap. On top of that, you have to make your rule book work for those who barely even read it!

Keep them clear, keep them concise, use lots of visuals, make them skimmable, and play-test a ton. If you do these five things, you’ll be well on your way.

Are you working on rules for your game? Share your experiences in the comments below 🙂