How Far Should Rule Books Go?

The quickest way to turn a brilliant game into a mediocre game is by botching the rule book. The game itself may not be ruined, but the experiences of the players will be dramatically altered for the worse. At first, the purpose of a rule book may seem deceptively clear: it’s supposed to teach players how to play the game. However, anyone who has struggled to create game rules that players can follow with no input from the creator understand that this can be a difficult task. Even as a raw knowledge dump, creating a good rule book is not unlike teaching a computer to make a peanut butter sandwich.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Many people see game rule books as a way to transfer information to players. I think this is short-sighted. Rule books should go beyond teaching information. They should teach intention as well.

A good rule book uses two techniques to teach intention in addition to information: context and guidance. Context can include a story that explains how different rules fit together. A lot of thematic games use story as a form of context to teach rules. In Twilight Struggle, you know, just from history, that when you’re playing as the USSR, your mission is to screw over the USA whenever you can. Context can also include examples of gameplay. Examples provide excellent context for players to understand how a game is played. In my own game, War Co., I extensively use examples to explain the trickiest concepts.

Guidance goes one step further: it provides practicable advice that players can actually use in the game. For example: “we recommend that you draw as many cards as you can, unless you have a reason not to” OR “try to keep cities from getting more than two disease cubes.”

Rule books need to be thorough, accounting for as many possibilities as they can. Yet they need to remain concise in order to be usable. Some would even argue that the presence of gamers like Rahdo or Watch It Played render traditional rule books obsolete. Yes, it is tempting to create a rule book that provides all information, abundant context, and lots of guidance for strategy and tactical decisions. However, if your rule book is too long, outside sources will end up explaining your game for you.

Likewise, you want to leave much of your game a mystery. A lot of the appeal of games is that their secrets are slowly unlocked as players discover more tactics and better strategies. By spelling out everything through abundant examples and highly specific advice, you may reduce your game’s longevity!

It’s a tough balance. Yet if you strike this balance, the reward is precious: you can prime a player’s experience. Your rule book is your best chance to not only teach players how to play the game, but to teach them how to have fun playing the game. The purpose of the rule book is to make sure the player has the most fun possible. The tools – information, context, and guidance – should go as far as they must to ensure this, but not any further.

As parting words, here’s six pieces of advice for you when you create your rule book:

- Make sure the player knows enough to play the game.

- Make your rule book concise.

- Leave a little room for mystery.

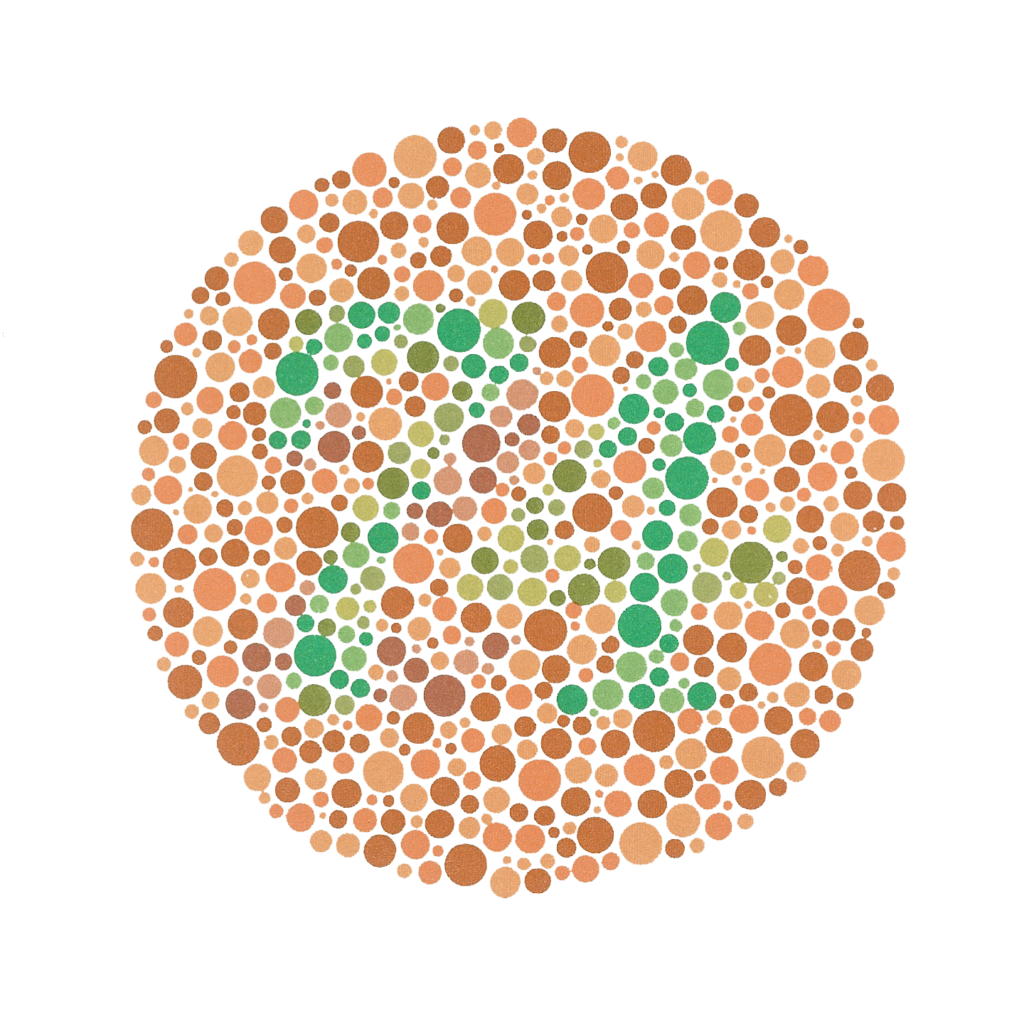

- Make it visual.

- Make sure it’s skim-able.

- Make sure it’s still useful even if players halfway read it.