How to Find an Artist for Your Board Game

It’s no secret that one of the most critical parts of making a board game that will sell is making it gorgeous. Box art alone has the ability to multiply sales of an otherwise unassuming board game. Finding an artist is something that many first-time board game designers find very difficult to do. Finding and taking care of an artist involves multiple expensive business transactions and a product whose quality can never be anything but subjective, so it’s very sensible to be worried.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

You don’t have to be worried, though, since I’ve got strong feelings about this subject and I’m here to share everything I’ve learned over the last two years 😉

In this article, I will cover five subjects:

- Making your project attractive to artists

- Looking for artists

- Reaching out to artists

- Sealing the deal

- Getting the best work out of your artist

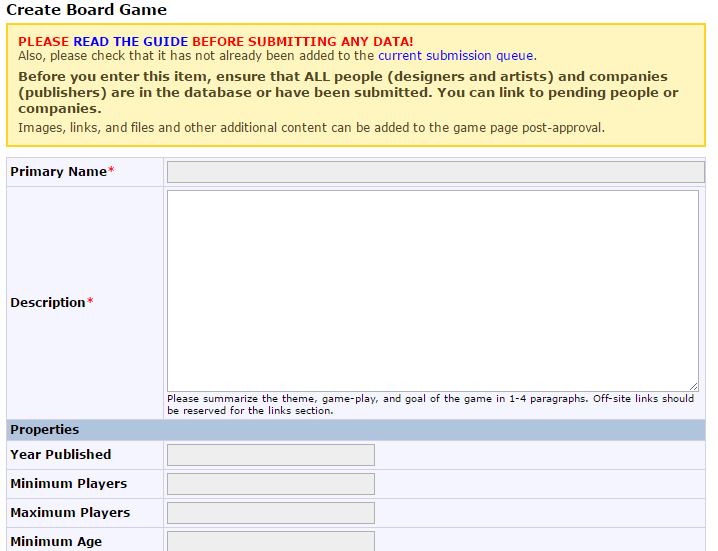

Step 1: Make Your Project Attractive to Artists

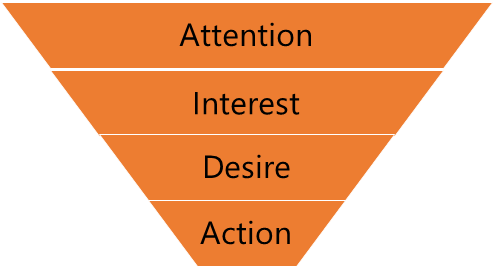

First things first, 80% of the battle is fought here. If you want to find an artist and get a good deal on money, you need to make your project an attractive prospect. Consider the incentives which artists respond to: pay, exposure, autonomy, and meaning. Pay attention to these things. You want to be a great client.

Pay: Artists make art for a living! That means that when you hire an artist as a freelancer, you need to pay them for their time and effort. For many projects, this will involve shelling out thousands of dollars. Unless you have a personal connection to an artist OR you hire someone very wet behind the ears, you cannot avoid this. By all means, negotiate on price, but don’t be a cheapskate. Since every project is different, you’ll probably want to make an art budget and set aside some cash and get a variety of quotes from different artists. If all the artists’ quotes are not even remotely close to your budget, you’ll have to scale down your art needs or set your sights lower on quality.

Exposure: If you don’t have a lot of money on your hands, you may be able to offer some intangible benefits. For example, if you have a large social media network and you commit to publicizing your artist as much as possible to improve their career prospects, you might be able to pay them less. In fact, this is how I got James Masino to do 300 unique pieces of art for War Co. for a price that I’m frankly embarrassed to disclose. Exposure is not “teehee, I’m on your portfolio which you can put on your website.” Exposure is “I’m swinging the full weight of a network that touches tens of thousands of people to get your name out there.” I did this until he was eventually offered a job for 10 times the pay by someone who was following me on Twitter.

Autonomy: Artists often work alone, especially the sort of freelancers who you might expect to get involved with board game projects. They like to set their own schedules, do work their own way, and be self-directed. Don’t micromanage. Don’t set unrealistic deadlines. Give them a chance to grow their careers as they create your work.

Meaning: People need to feel like their actions mean something. People especially need to feel like the toil they put into their labor is worthwhile and building something great. Look, we make board games. We don’t cure cancer. Yet if you can consistently provide your artist with context that tells them how their work fits into the larger picture and what it means to you personally, they will pick up on that and it will make their work sweeter. That’s so important and so often neglected.

Step 2: Start Looking for Artists

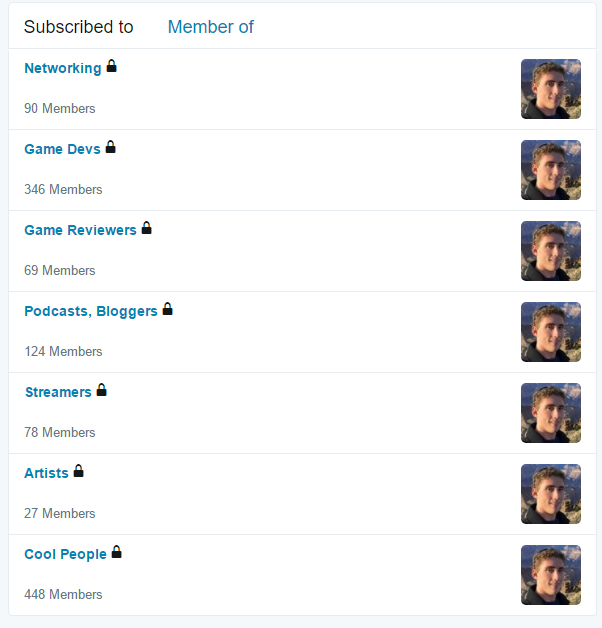

Compared to the above, this is simple. There are three fantastic places I know of where you can find no shortage of talented individuals. They are DeviantArt, Instagram, and Twitter. This is one of the many reasons I think social media is very important for game developers, but to take advantage of these websites to find artists, you don’t even have to be all that active. You can use the search features on all of these websites and start scrolling through work. Start clicking on bios and seeing who is active, available, and looking for work. Make a list of everyone you’re interested in. You’ll probably want about 20 people on that list. Ten won’t get back to you, five won’t be interested, and only one or two of the remaining five will end up being good once you start talking brass tacks.

Finding an artist is the simplest part of getting art on your project, but there are still some pitfalls. Consider whether you want a newbie artist or a veteran artist. Newbie artists are not hard to find and the market has a greater supply than demand, so if you have a good deal of money, you have the upper hand. If you’re looking for a veteran artist, it costs a lot, lot more. That’s the price of consistency, reliability, and a proven track record. If you’re working on a big budget game, by all means, go for a veteran artist. All things equal, I’d personally go with the newbie because their work can parallel veterans with the right instruction. Just be aware that choosing a newbie might save you some cash, but it could lead to low quality art and project delays. I’ve never had to deal with that, but it’s not uncommon and it’s a risk you have to bear.

When you’re looking for artists, make sure you pay attention to the sort of work they’ve done before. If you’re doing a sci-fi game, and all they’ve done is fantasy art, they might not be a good match. It’s still okay to ask, and I recommend that you do, but don’t get your hopes up. Likewise, if all the artist’s work is scenery and machinery, don’t expect them to paint decent looking people. If you have a variety of art styles in your game, you may even consider hiring multiple artists and divvying up the work according to specialty.

Step 3: Reach out to Artists

Once you have a list of artists who you believe would be appropriate for your project, it’s time to start shaking hands. By shaking hands, of course, I mean sending emails. Even though you’re likely finding the artists through social media or DeviantArt, I still strongly suggest you get their email and send them a message that way. If their email is not on their profile or they don’t respond to emails, that’s a red flag. Freelancers should be checking their emails pretty often. Remember what I said above: about half of who you email won’t get back to you, so you can just cross them right off your list.

Let’s say you’ve got your email client up and you’ve got their address in the To box. Oh, but what do you say? Well, I’ll copy and paste my first email to James Masino, the artist for War Co., and we’ll break it down sentence by sentence – all the rights and wrongs. Then I’ll give you a template.

Hi James,

I am working on a trading card game called War Co. It has a sci-fi post-apocalypse theme. I’ve been looking for an artist for a while, and our mutual friend Alex said you might be the right guy to talk to.

I checked out your site and it’s pretty cool! You have an impressive set of skills with a variety of tools that I’ve only played around with for a few hours. I would like to work with you in the future on creating the artwork for my game.

Just to be clear, I’ve never taken on a project of this scale before. I’ve never needed to work with an artist, so I don’t know what the process involves. I’ve got an overall method to my madness as well as a written plan, but there’s a lot of things I’m still working out.

Thank you and looking forward to your reply,

Brandon Rollins

[My Personal Email]

[My Personal Phone Number][War Co. Website]

I am working on a trading card game called War Co. I immediately explain the nature of my project. (I changed the genre to “expandable card game” later on, but that didn’t affect art.)

It has a sci-fi post-apocalypse theme. This lets him know what to expect as far as art style.

I’ve been looking for an artist for a while, and our mutual friend Alex said you might be the right guy to talk to. I explain what I’m looking for from him and how I found him.

I checked out your site and it’s pretty cool! You have an impressive set of skills with a variety of tools that I’ve only played around with for a few hours. I explain why I’m reaching out specifically to him and not someone else.

I would like to work with you in the future on creating the artwork for my game. I state again specifically what I’m looking for.

Just to be clear, I’ve never taken on a project of this scale before. I’ve never needed to work with an artist, so I don’t know what the process involves. I’ve got an overall method to my madness as well as a written plan, but there’s a lot of things I’m still working out. I’m torn on how I handled this. I might have tipped my hand a bit too much with what I don’t know. However, if you need the artist to take the lead on setting realistic deadlines, make sure you make that clear.

[Contact Information] I made sure to give him two ways to contact me, as well as a link to the website so he could read more. By then, I already had an enormous amount of information online about the game so he could know what he’s getting into.

You’ll notice that price did not come up at all the first time around. Before you even discuss price, let the artist get back to you and tell you whether or not they’re available and whether or not they’re interested. Very few will get past this stage, and at that point, it is fair to ask about price.

Here’s a template you can use for that first email.

Hi [First Name],

[Describe your project.] [Describe desired art style.] [Say you’re looking for an artist.]

[Say how you found the artist.] [Explain why you like the artist and reached out to them.] [Reiterate that you’re looking for game art.]

[Give a rough overview of your game as a project.]

Thank you and looking forward to your reply,

[Your First and Last Name]

[Your Email]

[Your Phone Number][Your Website]

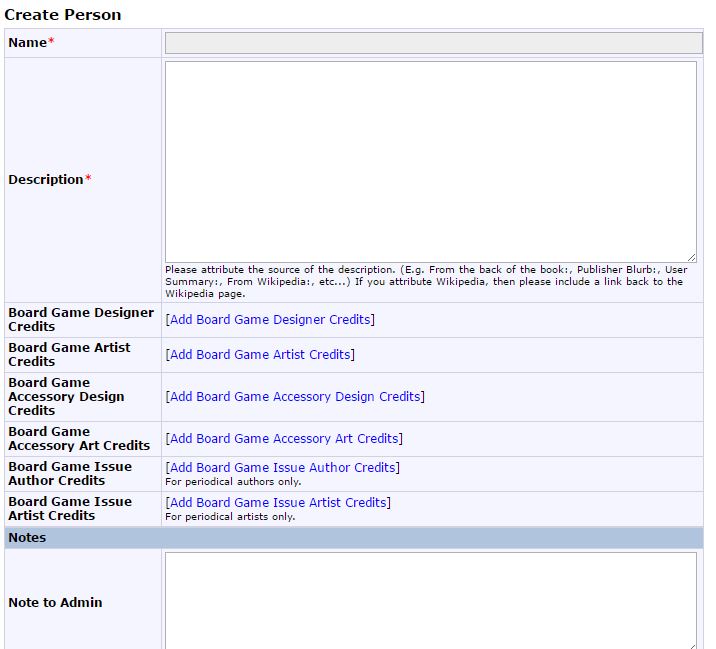

Step 4: Seal the Deal with the Artists

At this point, you’ll soon find yourself in a discussion about payment amounts and schedules, contracts, and royalties. I cannot give you templates to get through this phase. You’ll have to rely on your own good judgment. However, there are some tips which I strongly suggest you follow.

- Make sure you get a contract. Make sure it’s clear and make sure you both sign and date it. Notarize it if you feel the need.

- When it comes to price, you have some negotiation room. However, if it’s way out of your budget, you’ll simply have to walk.

- Make sure the art is made on a “work for hire” basis. That means upon payment, you become the copyright holder – not the artist. This is so, so important!

- If you offer a royalty, I’d suggest between 2-5% split between all artists involved in the game. I’d also suggest making the royalty apply only to sales after Kickstarter and pre-orders. Applying a royalty fee to the tender early state of your fundraising could really hurt you in terms of cash flow. Offering more than 5% could also really hurt you in the long-run because there are so many factors that go into getting a game published.

- Set schedules and milestones for when certain parts of the art will be done. Adjust them as necessary if they turn out to be unrealistic, but have a spine if you find out you’re being played by a procrastinator.

This is hard to do right. Make sure you communicate very clearly and stay focused on the needs of everyone involved.

Step 5: Get the Best Work out of Your Artist

Once you start discussing money and contracts, you’ve already succeeded. Yet if you really want to take your art up to the next level, you don’t just have to depend on your artist. You have a pretty solid amount of influence as the game developer. Indeed, you can push a good artist to make great art by doing three things:

- Be completely straightforward about your business needs and intentions.

- Be as specific as possible when providing art directions.

- Provide instructions that are consistent with good marketing practices.

You want your artist’s trust. Game development is a long, winding journey and a single game will almost certainly not make you rich. You want to focus on developing good relationships, so you need to be really straightforward and honest with your artist about where your business is, where you expect to go with it, and how much you can afford. It takes time to develop an instinct for this, but if you keep this all in mind and keep trying, you will figure it out. You want long-term contacts. Artists know other artists.

Regarding art directions: the more detailed you can be, the better. You want to strike a balance between giving your artist freedom and giving them direction. You want rework to be minimal, because that is absolutely exhausting for an artist. When you provide those directions, make sure you provide directions that make art pop on the shelf. This is hard to explain, but I’ll just show you what I said to James.

Narrative Themes:This game’s story is about corruption, bureaucracy, conflicts of interest, group psychology, war, trauma, resilience, hope, and pyrrhic victories. Sometimes it’s about the mundane application of high-flying technology, sometimes it’s about disappointment, sometimes it’s about miscommunication. There’s a ton of themes, and I made no effort to stick to one. I picked slices of a complicated world to throw on the floor with no rhyme or reason. Every person will make their own narrative. I’d argue traditional media like novels and films work the same way. I’m just being more blunt about it. Each card has its own theme, basically.Visual Themes:From a business and game perspective, there’s one thing I’m trying to ensure in this game that I don’t see anywhere else: simplicity. Trading card games are nerd territory because they’re complicated. Superheroes used to be in the same boat before the turn of the century. When drawing pictures, be conservative about your level of detail. I’d like it to be sharp, snappy, and to leave an immediate impression. That doesn’t mean you can’t make large hulking ships with baroque levels of detail…it just means pay very close attention to how the viewer’s eye will be directed. Whether this translates into photorealism or simplified/smoothed-out reality, I leave to your better judgement. User-friendliness is how I plan on playing alongside the big kids like Magic, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and Pokemon TCG.I’m trying really hard to avoid the stereotypical annoying client “make it pop” speech, so I’ll use a visual example.

I’ll use Mad Max: Fury Road. That movie was fantastic! Here’s some things I like about the picture below:

- It’s clearly violent and post-apocalyptic, but it’s also bright and colorful. Too many people associate “apocalypse” and “gray/desaturated.” I think that trope is cliché.

- The most important details are up-front, immediate, visible, and I’d even say “right up in your face.” Once you process the immediate part, then you can say “oh wow, there’s actually a lot going on here. Who’s behind him? What’s with the fire? Look at his gross neck sweat!” and so on.

We had some further conversation in next few emails and he said that he really appreciated these instructions. What you don’t see is that I had about a 200-300 word story for each piece of art, but otherwise left it up to interpretation. James’ response to these instructions was to create art like the following, which has been praised as a strong point of the game by nearly every review of War Co.

Key Takeways for Game Devs

- The most important part is making your project attractive to artists.

- Pay your artists as well as you can.

- If you have a large online following, do everything you can to promote your artist – especially if your pay is low.

- Respect your artist’s need for self-direction.

- Give your artist context to know how their work fits into the larger picture.

- Find artists on DeviantArt, Instagram, and Twitter.

- Make a list of 20 artists who you like.

- Think about whether to hire a newbie or a veteran artist – both have advantages and disadvantages.

- Make sure you find an artist who is experienced and interested in the themes and styles you’ll need for your game.

- Send a polite email to all the artists on your list. See my template in section 3.

- Use good judgment when you’re committing to an artist.

- Get a contract.

- Negotiate some, but don’t be a cheapskate.

- MAKE SURE THE ART IS DONE ON A WORK FOR HIRE BASIS!

- Offer a royalty that is no greater than 5% split between all artists.

- Set schedules and milestones for when parts of the art will be done. Adjust as needed.

- Communicate very clearly and stay focused on the needs of everyone involved.

- Give specific art directions that have marketing in mind.

- Be good to your artist. You need long-term contacts. Artists know artists.