How to Learn Complex Material Quickly

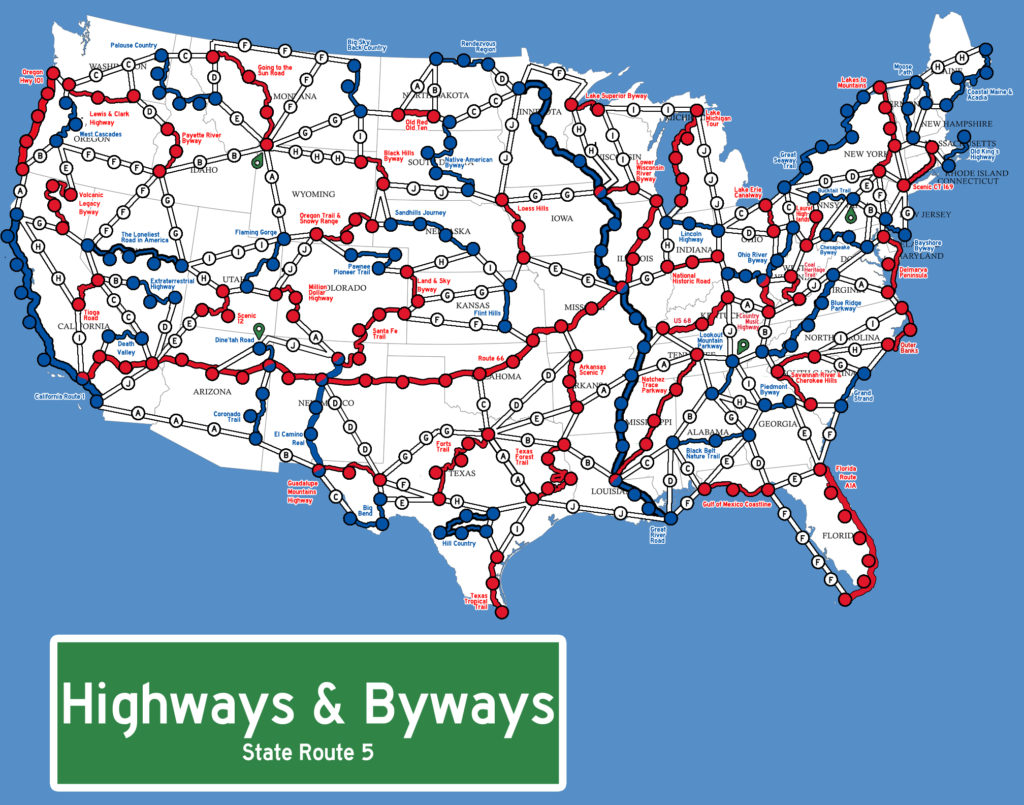

Dev Diary posts are made to teach game development through specific examples from my latest project: Highways & Byways.

Just here for Highways & Byways updates? Click here – it will take you right to the updates at the bottom of the page.

Over the course of the last week, I’ve taken a bit of a left turn in the development of Highways & Byways. Instead of focusing directly on game development, I’ve focused on learning as much as I can about board games. That includes popular games, mechanics, and themes; well-known designers; and how to run a successful Kickstarter. I’ve advocated before the importance of ongoing training, and I’ve focused very heavily on it myself this week.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

Why go to all this trouble? A lot of new designers see that I’ve published War Co. and imagine that future Kickstarters will just be more successful from there. Future games will be better by the mere act of having experienced the development process before and being aware of some of the pitfalls and opportunities to be more productive. My community continues to grow. This is all true, but I see room (read: a vast expanse) to improve even still. Experience gives you advantage, but it cannot substitute for systematic book learning. If you want to get better at something, you have to continually and thoughtfully work for it.

With this in mind, I’d like to share with you a learning technique that I came up with late in my undergraduate studies. Ever since I developed it, I got A’s in all my classes for the rest of undergrad and grad school. It didn’t take nearly as much work as you’d think, either. I didn’t do anything particularly special. This technique is something that you can apply to almost anything you’re interested in and see similarly positive results.

The Study Technique

1. Find primary resources. In school, primary resources were textbooks and lectures. In the world at large, primary sources can include all sorts of things: data from your business, academic journals, videos, blogs, magazines, news sites, social media, books, and so on.

2. Read the Overview so you so you know what to expect. The Overview could be an actual overview paragraph, a summary section, a Table of Contents, a list of blog articles, or the abstract of an academic article. Sometimes this is not available, but in long-form material, it usually is.

3. Read the primary resources all the way through, slowly, taking in every word. Take it slow and stay focused. Pay attention to every word and every image. Don’t get too mired down in the details, but take in as much as you can the first time.

4. Start taking notes. Go through the entire resource and start taking notes on your computer. Every header, every definition, every bit of bolded text, every numbered list, every bulleted list, and every sentence that looks generally important should be in the notes. Adapt these rules to the medium you’re pulling information from. There are signals of important information in anything you pay attention to.

5. Read the notes once every day, even if it’s speedreading.

6. Bonus: make flash cards and start memorizing your notes. You can use a tool such as Quizlet to make flash cards online. For most situations, this is overkill, but it works really well in school and in high-pressure situations.

This is a time-consuming, difficult, painfully boring technique, but I promise that in can save you time, difficulty, and boredom in the long run. In school, I cut my study time by about 25% and my grades went up.

It’s not just for textbooks, though. You can apply this to a variety of skills if you choose your sources wisely. Want to learn cooking? Use this technique with a cookbook. Want to learn home repair? Use this technique with a home repair podcast.

Want to learn game development? Use BoardGameGeek’s database, blogs such as Stonemaier Games Kickstarter Lessons, Dice Tower videos, design books such as the Kobold Guide to Board Game Design, and even academic research papers (which you can find on Google Scholar). Obviously, you still need to be experimenting and developing your own games, but this information will help you get to the next level in your development.

The repetition and hard work are half of what makes this technique work. The other half is that its designed to help you gather and remember only the most important information. We can’t remember everything, so we must be careful to remember the right things.

Key Takeaways for Game Devs

- Experience gives you advantage, but it cannot substitute for systematic book learning.

- Periodically focusing on ongoing training can make you a better development.

- You can use the same study technique I used to get A’s in grad school to learn game development.

- The study technique:

- Find primary sources

- Read the overview of each source

- Read the entire primary source all the way through slowly

- Take detailed notes on each source

- Study the notes

- Bonus: make flash cards and memorize the notes

- Some good primary sources for game development: BoardGameGeek, Dice Tower videos, Stonemaier Games Kickstarter Lessons, the Kobold Book of Design, academic journals.

Most Important Highways & Byways Updates

- Though I’ve primarily been studying game development this week, I’ve made quite a few updates on the game still.

- I’ve updated the game to Version State Route 8, and it’ll probably be State Route 9 by tomorrow.

- Rules have been cleaned up so I’m using consistent terminology.

- I moved starting spaces around on the map so they’re more balanced.

- I broke the hardest roads into two sections for both balance and simplicity.

- My brother and I have play tested the game again and we agree that while it’s good, something is missing and we’re having trouble defining it.

- I’ll be doing a “paper test” soon. I usually play test in Tabletop Simulator to save money, but I need to make sure the physical size of the board works as designed and I need to make sure it’s not too fiddly to play the game in real life. This is a necessity that comes with spending most of your time doing digital testing of a physical product.