Creating the Perfect Board Game Scoring System (Tasty Humans Pt. 2)

Creating a great scoring system in a board game can be a difficult process. Once you craft the basic concepts of your game and find the right mechanics to express them, you have to set rules. Scoring rules are among the most important, particularly in euro games. So how do you do it? How do you make an arbitrary point system feel fluid and connected to the underlying ideas in your game?

Many of you know that our Kickstarter campaign, Tasty Humans, has just debuted on Kickstarter! Both to celebrate the launch and to share knowledge, I’d like to share the thoughts of Ryan Langewisch, designer of Tasty Humans. He, after all, created the pattern building game that we call Tasty Humans, so it makes for a great case study!

His unedited original post can be found here. Below, I have lightly edited the original work from his blog and – in some cases – replaced images with ones from the production copy of Tasty Humans. Enjoy!

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

In my first Designer Diary post for Tasty Humans, I talked about the mechanics of dropping shapes (which represent the titular “Tasty Humans”) in order to fill up the stomach of the each player’s monster. Now I want to dive into the goals that players are actually trying to accomplish. Let’s talk about how those goals emerged during the design process.

Scoring on a Full Stomach

I decided that the basic gameplay was going to involve filling up a grid with tiles. Next, I needed to figure out what would work best as an objective. What determines how well that player did given a grid is filled with different tiles? What determines the satisfaction level of their monster? I needed some criteria that would score “satisfaction points”. It was clear that it would have something to do with pattern-building and positioning tiles in specific arrangements.

The first idea I had was for all players to have public scoring objectives that they are trying to achieve. Before every game, the objectives would be randomly selected. This would have likely worked fine. However, it didn’t feel like it captured the variety and interactions that I was looking for in the gameplay. I like the idea of having localized scoring conditions that could apply to different portions of the board. An example would be scoring for placing a certain tile type in a specific column. But how would the scoring objectives define what portion of the board they applied to?

So What Next?

This led to the following idea: what if the scoring conditions were actually inside of the grid? For example, maybe you have a special tile in your stomach that scores for being near a certain tile type. There would be a few implications to this approach.

One, the positioning of the objectives would matter. The positioning opens opportunities for a lot of interesting goals that deal with pattern-building relative to the tile’s own position. Two, it would allow each player to have entirely different objectives. This caused the goals among players to branch asymmetrically as the game went on. Lastly, based on the combinations of scoring tiles and their position relative to each other, it could lead to a varied interest based on the combinations of scoring tiles. This idea developed into what ultimately became the backbone for scoring in Tasty Humans. Players have the opportunity to draft “Leader Tiles” throughout the game. Dropping the tiles into their monster’s stomach add to the definition of what “satisfaction” means for that monster.

Layering Scoring Interactions

Each time a player drops a new Leader Tile onto their board, it creates a new layer of scoring opportunity on top of the same grid of tiles. Every game these combinations are going to be different. Players will need to tactically drop adventurers into their monster’s stomach in an effort to maximize the cumulative satisfaction points. Consider the partially filled board shown below.

At this point in the game, the player has acquired three different leader tiles. The tiles are one that scores 3 points for every column that has each of the four tile types. Another that scores 2 points for hand tiles that are diagonal from it. And, finally, one that scores 2 points for each boot tile in the same row or column.

Examples of the Scoring System at Play

In Column 1, I should really try to place a hand next because it would actually serve two purposes. It would score 2 points for being diagonal from the hand leader tile. Since it would also be the first hand in the column, it is moving closer to scoring the 3 points for having each tile type.

Neither Column 3 nor 4 has spaces that apply to the hand and boot leader tiles. Therefore, they may be good candidates for dropping “collateral” tiles that come when I am trying to drop specific tiles into some of the neighboring columns. However, if possible, I should try to make that “collateral” move towards having each tile type in column 3 (whereas column 4 already has all the tile types).

All the spaces in Column 5 can score from boot tiles. However, I know that it is unlikely I will be able to find the right pieces to completely fill it with boots. The second empty space from the bottom could also score if it was a hand tile. Maybe I should target that as a one of my “non-boot” spaces. I also need to decide whether I want to try to get each tile type in that column. However, that directly conflicts with trying to fill it with boots. Maybe I will try to go mostly for boots. But when that isn’t possible, try to fill it in with the other tile types to keep that option available.

The Optimal vs. The Tactical: Scoring Decisions on the Fly

All of these observations stem from only looking at the player board. If you recall from my post on dropping shapes, there is also a lot of variation in how you can drop a new piece into your board. These elements combine to create the central puzzle of each turn in Tasty Humans. How do I rotate and position my piece in order to best work with my various Leader Tiles? You won’t be able to optimize everything perfectly. Therefore, you have to make tactical decisions about where to make sacrifices and where to focus your scoring efforts.

As I explored the design space created by these Leader Tiles, I found that they fell into two categories. The categories where the position of the tiles mattered, and where it didn’t. For example, in the board shown above, the boot and hand Leader Tiles both score spaces relative from their own position. For column variety, you can place the Leader Tile anywhere and it wouldn’t make any difference. From a design standpoint, I definitely preferred the positional effects. I find it makes for a more interesting decision when you are placing them into your board. I realized that some cool effects only makes sense being universal. Column variety is one such example. In the end, I tried to strike a balance between having mostly positional scoring effects but including universal effects. I included the universal effects where I felt that they added enough interest to justify their inclusion.

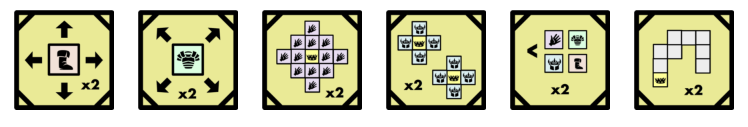

At this point in the development process, there are 30 total Leader Tiles. They are all unique (though many are the same effect for each tile type, e.g. scoring for tiles of a type in the same row or column). Let’s take a look at one more example that shows some of the more interesting effects that may come into play.

Breaking it All Down

Let’s break down these Leader Tiles from left to right:

In column 1, we have a Leader Tile that scores for the number of spaces to the nearest hand tile in each of the eight directions. So we want to place hand tiles in line with it. Ideally they would be separated by several non-hand tiles to maximize the distance.

In column 3, we have a Leader Tile that scores 2 points for each boot tile that is next to any Leader Tile. We will want to keep this in mind for the three Leader Tiles we have now, and also when we are placing any future Leader Tiles.

In column 5, we have a Leader Tile that scores 2 points for each tile in the longest chain of the same type, starting from the Leader Tile itself. For example, the three helmet tiles represent the longest chain on the board. This would score 6 points.

Profound Impacts of Subtle Scoring Rules

You can start to see how the considerations based on Leader Tiles are not always trivial. For example, which tile type should you pursue for the “snaking” Leader Tile? Right now the helmet tiles have the most. Nevertheless, there is potential to string the armor tiles together as well. Additionally, getting a string of armor tiles to move up the far left column would also pair well with waiting to place a hand tile until the very top. This would maximize the distance from the Leader Tile in the bottom-left corner.

On the right side of the board, it is clear that a hand tile would be best in the far right column. However, what is the best approach for the spaces above that? A boot would score next to the Leader Tile. However, a couple of helmets could also extend the chain of helmets to five tiles, while still keeping it “alive” for extension higher up in the board. The bottom-left Leader Tile also requires you to be careful not to prematurely drop a hand tile somewhere too close to it. For example, if you were to accidentally drop a hand tile in the second column while positioning other tiles, it would only score 1 point on that diagonal. If you could space the nearest hand all the way out to the rightmost column, you would score 5 points.

Of course, these questions can only be answered once the player considers what adventurers are available. This will dictate the shapes and tiles that they have to work with. But even before checking which shapes are available, a player can mentally prepare much of their approach from simply analyzing the current state of their board.

Final Thoughts

As I mentioned at the beginning of the post, the question posed by this design was, “how do you score a stomach (grid) full of tiles?” The desire for a high level of variability led me to these Leader Tiles; scoring objectives that are actually included in the grid itself. Hopefully the examples in this post give a taste of the decision space that these tiles create, and why I ultimately felt it was the right direction for the design. Leader Tiles didn’t solve all of my problems when it came to scoring though… In my next Designer Diary post, I will talk about how having Leader Tiles as the sole scoring objective often left many spaces in the board that had no scoring impact. This led to the addition of “personal cravings,” which are universal scoring conditions that are different for each monster in the game.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this insight into Ryan’s creative process. By sharing our experiences in the development of Tasty Humans, we hope to help you create games that you are proud of, too