Board Game Pacing: Keeping Your Game Interesting (Tasty Humans Pt. 5)

Perfect board game pacing is one of the most underrated aspects of board game design. Somewhere between overwhelm and ennui, there lies a middle ground where a game is perfectly paced. A great board game feels challenging and interesting throughout. So often, when we’re balancing our designs, it’s because we’re trying to nail down board game pacing.

But how do you do that?

Many of you know that our Kickstarter campaign, Tasty Humans, has just debuted on Kickstarter! Both to celebrate the launch and to share knowledge, I’d like to share the thoughts of Ryan Langewisch, designer of Tasty Humans. After all, he created the pattern building game that we call Tasty Humans, so it makes for a great case study!

His unedited original post can be found here. Below, I have lightly edited the original work from his blog. In some cases, I have also replaced images with ones from the production copy of Tasty Humans. Enjoy!

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

In each of the design diaries that I have written so far, I have focused on a specific game mechanic or isolated portion of the game. Now I want to zoom out a bit and look at the design as a whole. I am putting more focus on the arch of the game of Tasty Humans and some of the decisions that were made. I made these decisions in an effort to improve game flow and the overall player experience. Early in development, I realized that the game would be best if I could fit the experience into a 30-60 minute time frame. This became a design beacon when making decisions around the flow of the game.

Game Progression and Board Game Pacing

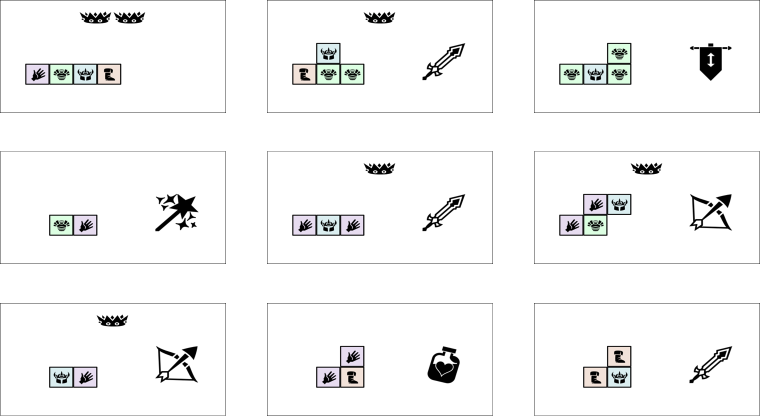

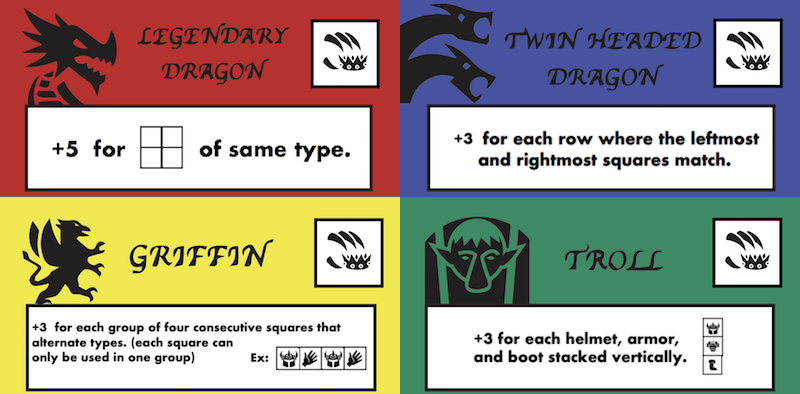

The progression in a game of Tasty Humans comes from the gradual filling of each monster’s stomach. There is also an escalation in strategy as the players fill up their boards by acquiring more and more Leader tiles. Each Leader tile provides an additional goal for how to maximize the “satisfaction” of their monster. At the beginning of the game, a player’s objective is simple. They have just a single Leader tile and their monster’s unique “personal craving.” Acquiring more Leader tiles gives the player more to try to balance. I have found this gives a satisfying feeling of progression from the beginning of the game to the end.

However, there were several possible implementations that would maintain this sense of progression. An early design question became, “what should dictate the pacing of players receiving new Leader tiles?”

In my first prototype, I had special “Draft Leaders” cards shuffled into segments of the Adventurer deck. This led to uncertainty in when players would get their next Leader tile. This proved to be awkward because it caused sudden interruptions of the rounds. These interruptions required players to put their tactical planning on hold to make an unforeseen decision about their next Leader tile. Also, it caused me to lose control of my own design. The random nature of the cards could lead to suboptimal player experiences if the cards came up too early or too late. A simple solution turned out to be the most effective. Leader tiles are always drafted on the same cadence, after each round. This not only allows players to plan for it, but also gives the game a much better rhythm.

Leader Tiles & Board Game Pacing

The original design for the Leader tiles was to wait and reveal them right before the draft was going to start. I initially liked the idea of it being a surprise. However, in hindsight, the decision trivialized the “crown” mechanic that I had included to determine the drafting order. How can players evaluate taking crowns to improve their order in the draft if they have no idea what their options will be? This question led to the decision of revealing the upcoming Leader tiles at the beginning of the round. Thereby, giving players the opportunity to better estimate how important it will be for them to secure an early pick in the draft.

Because of the desired pacing for the game, I decided that a Leader tile draft should occur after each player has selected (and eaten) two adventurers. However, this ended up feeling a little clunky. It required players to remember if they were on their first time around the table, or their second. Rather than having a natural pattern to each round, it felt like the round was “repeat the same thing twice, but remember if it is the second time.”

Snake Draft & Board Game Pacing

Striving for a more elegant solution, I played with the idea of making it a snake draft; that is, going around the table, but then reversing the turn order back and finishing with the first player. Searching for a better solution, I played with the idea of making it a snake draft. A snake draft goes around the table only to reverse the turn order back and finish with the first player.

With this approach, each player would still pick two adventurers. However, the end of the round would be more clearly defined when play moved back to the start player. I found this to work well in testing. While making the rounds feel much more natural, it also had some interesting side effects. The player that gets back-to-back turns in a round has some opportunities to be clever in how they manipulate the adventurer grid to their advantage. Even so, the decision wasn’t without its downsides. The main one being that the first player has to wait twice as long for it to be their turn again. While not ideal (especially if some of the players are struggling with analysis paralysis), I deemed that the advantages tipped the scale in favor of the snake draft. In playtesting, the time between turns has rarely been an issue.

The Race to the Finish

From the beginning, it was clear to me that filling the monster’s stomach should trigger the end of the game. It is not only satisfying for the players to completely fill their grid, but it is also thematic for monsters that are appeasing their hunger. Yet, I quickly learned that it was not a good approach for the game to end immediately after a player fills their board. Technically, other players should have the awareness to see what is about to happen.

Nonetheless, this approach almost always left the other players disgruntled at not being able to finish what they were planning. In a game like Tasty Humans, each player is primarily lost in their own world of puzzle-solving. As a result, I found that I needed to let players follow through on their plans without any sudden interruptions. The simple solution was to always finish out the current round (i.e. snake draft) once one monster filled their stomach. It is funny how often the simple solution is the best one.

Simplicity Sometimes Leaves Questions Unanswered

I still had one unanswered question. Should the player that filled their stomach first receive any kind of reward? Initially, I was a little hesitant to give the fastest player points. I did not want a “rush” strategy to be the most effective way to play. Ultimately, I wanted winning to come down to who best maximized their scoring conditions. This was accomplished by how they had arranged the tiles in their monster’s stomach.

However, there was another design incentive in rewarding a player for triggering the end of the game. That incentive was shortening the play time. The design goal of keeping the game length within the 30-60 minute range was important. Basically, my end game condition meant that the fastest player would determine the game length. I encourage players to push to the finish instead of stalling for more points. This aligns their goal of winning with my design goal of keeping the game from running too long.

In the end, I made filling your monster’s stomach first worth a modest (but not insignificant) 2 points. I then ran some specific tests to ensure that a “rush” strategy was not dominant. Fortunately, due to how points are scored and how detrimental damage can be, the “rush” strategy wasn’t dominant. In fact, the strategy proved to be far inferior to a slower and more precise approach.

Board Game Pacing for Different Player Counts

Another hindrance to a consistent 30-60 minute playtime was scaling based on the number of players. Obviously, if it takes two players a certain amount of time for one of them to fill their board, it is going to take even longer with four players. To achieve my design goal, I needed something to change that would compensate for the slower filling of the board in games with more players.

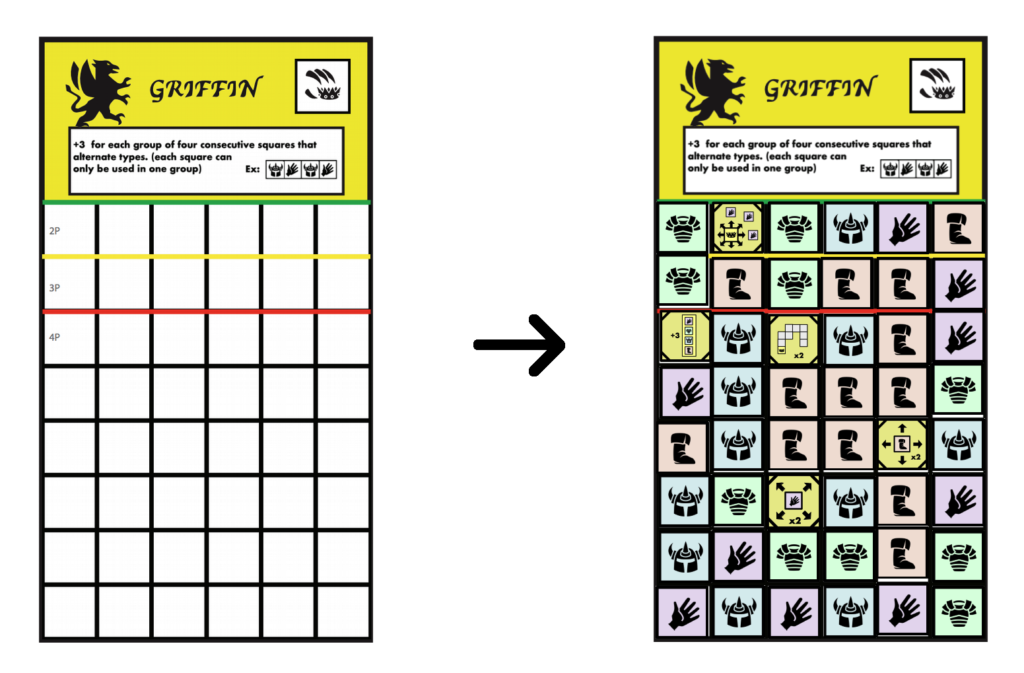

The only obvious solution scared me a bit. That option was using a smaller grid with higher player counts. I was concerned because much of the satisfaction of the game comes from filling your board. That satisfaction meant having a lot of space to work with and score points. I was afraid that if I reduced the rows in the grid, players would feel stunted. I did not want them to feel as though they were just getting a teaser of the “full game”.

This is an example of how simple playtesting of a change can trump what you, as the designer, “thinks” will be the effect. Despite my skepticism, scaling the number of rows in the grid based on player count worked flawlessly. Even at the highest player count (4 players), every game still felt like players had the full experience. Players have left frequent feedback stating their surprise at how much they felt like they accomplished in such a short playing time. This is one of the best indicators that the game pacing is on the right track.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this insight into Ryan’s creative process. By sharing our experiences in the development of Tasty Humans, we hope to help you create games that you are proud of, too