Creating my first game, War Co., is one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done in my life. It also happens to be, not coincidentally, the hardest project I’ve ever worked on. I’ve had so many rude awakenings and heartbreaks over the course of the nearly two years I’ve been working on it. Below, I share four rude awakenings I’ve had during the development of War Co. and how I’ve overcome them.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

1. There are far more game developers out there than I thought.

When I first started working on War Co., I didn’t realize the sheer size of the board game community. I had a foggy idea that there were lots of people creating games, but I didn’t intellectually or emotionally understand that thousands, perhaps millions, of people were trying to do what I was trying to do. On Twitter, between the War Co. and Brandon the Game Dev accounts, I follow over 500 board game developers. That’s just the ones I’ve got sorted into Twitter lists, too, the real number is probably well over a thousand.

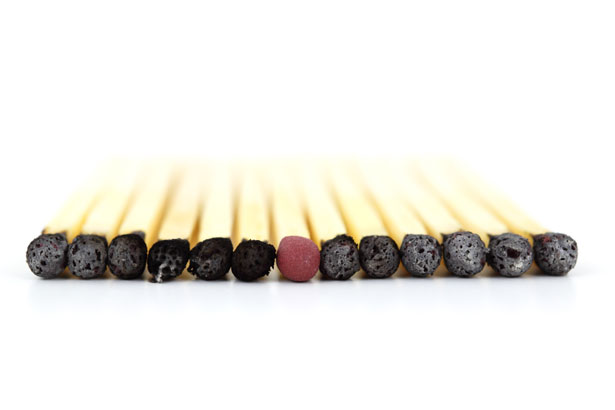

It was hard for me to accept that there were thousands of people trying to do what I was trying to do. It’s harder still to accept that the vast majority of them will fail. I slowly came to realize that this was my pride and fear talking.

Game development is cool. Seems like everyone wants to get into it. The vast majority of people who call themselves developers aren’t serious. The ones who aren’t serious fade away in less than a year, usually, but their sentiments remain online like ghosts. Just by sticking around, I realized I was doing better than most game developers. The same principle can apply to you…if you stick around.

Then I realized something more profound – we can all lean on each other, sharing ideas, commiserating, opening up our hearts to one another. Your fellow game developers will very often be your biggest fans, wisest mentors, and best friends. I became a member of the game developer community.

2. Kickstarter isn’t as indie as I thought it was.

I’ve written at length about my ideal version of Kickstarter. It’s no secret that much of my game development knowledge was formed in my attempt to process the raw emotions that came with my first Kickstarter campaign’s failure. To make a long story short, you must have a very polished game and campaign to succeed on Kickstarter if you’re a first-time game developer. I had a magical viewpoint of Kickstarter, and that was pretty brutally taken apart in one very hard week.

Thankfully, I didn’t make the mistake of assuming Kickstarter would provide the crowd. I had a social media presence for months beforehand. What I didn’t have, however, was any idea how social media traffic would translate to Kickstarter, a game more than halfway complete, reviews, testimonials, contacts within the board game community, or accurate cost estimates…

Shit. This is hard for me to admit to you right here. Don’t make the same mistakes as me.

I wanted to improve, so I got deeply involved in the board game community, continued my social media marketing, finished the game, got about ten reviews, and fire-proof cost estimates. I relaunched at a higher goal of $10,000 and earned $12,510.

3. Many of my biggest potential fans were burnt out.

I found that a lot of the people who loved board games the most were also the hardest on them. I call them early adopters – they’re the folks who will take a risk on a mediocre Kickstarter because they love ideas and want to be the first to try the newest, coolest thing. They’re super-fans and they love, love, love board games.

These very same people who will back you when no one else cares are the harshest critics. They play a lot of games, and they are – whether consciously or not – sizing you up to the greatest games of all time. No pressure. They’ve also been burned by a lot of bad Kickstarters, been hassled to try a lot of garbage PNPs, and generally seen a lot of lousy hijinks in their time.

I learned to listen to them. I learned to observe Twitter trends, read Reddit threads, and scour BGG ratings. If you stay involved, you will understand the pet peeves of your niche audience. You will understand their loves and hates, their pains and pleasures. It takes time. Thankfully, many people who love games the most aren’t shy about telling you what you can do better. If you can handle harsh criticism, it can make your game – and indeed, you yourself – stronger.

4. It takes longer than I thought to design a game.

This bears little explanation, but it’s quite possibly the biggest bear of them all. I thought it would take about six months to make War Co. That was naive. The truth was that it took a lot longer than that – almost every game does. Only thing I knew to do was keep sticking with it. Keep showing up. Keep looking for ways to improve.

I’ve had a long journey. It’s been a road of many twists and turns for me. I leave you with these parting words of advice:

- Stick with it.

- Start a Twitter account. Follow at least 100 game developers – both successful ones like Gil Hova and Jamey Stegmaier, and struggling ones as well. Organize them into a Twitter list. Keep tabs on their projects.

- If you want to Kickstart your game, get it 90-95% finished before you campaign. Build a big social media audience with a lot of one-on-one interaction. Ask your followers, privately and directly, for their feedback. Listen to them. Continue this process for a month or two.

- Figure out who your game is for. Find the places they hang out. I suggest using Twitter and creating Twitter lists of people who like your style of game. Watch them gush. Watch them complain. Take notes, adjust your game and your business around their needs.

- Seriously, stick with it.