Game development is a notoriously iterative process. Your final game will bear little resemblance to your first draft. The best way to make a good game is to play-test it to death, hammering out all the inconsistencies and problems. This is incredibly time-consuming and disheartening. Don’t let it bother you.

Looking for more resources to help you on your board game design journey?

Here you go: no email required!

Like this writing style?

Check out my latest blog on marketing here.

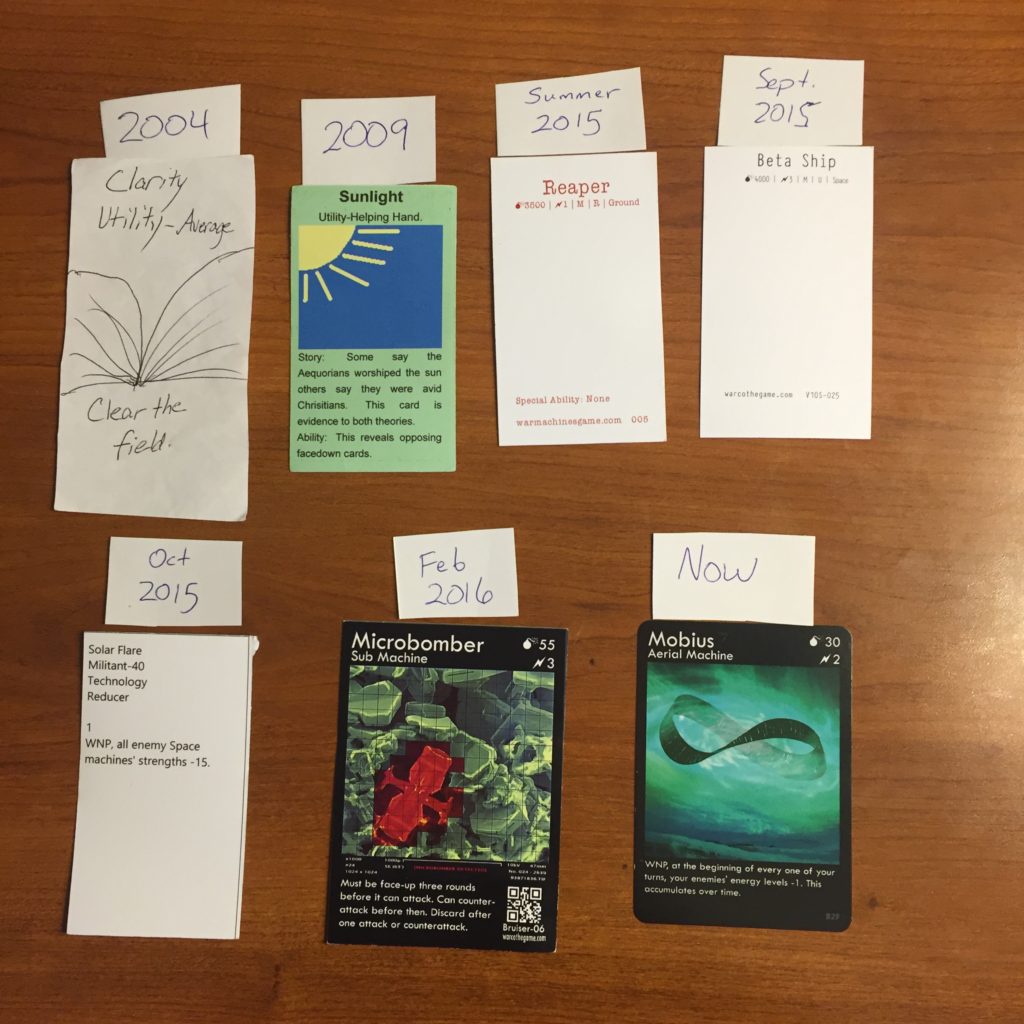

My first game, War Co., went through 17 iterations before its final version was ready for manufacturing. I think I got off easy.

Feedback and play-testing is critical. Yet even good play-testers can usually only “point and grunt” at the true underlying problems in your game. Before you play-test your game with other people, make sure you know what type of game you’re trying to create. Come up with the basic feeling you want your game to evoke, an overall objective, and basic constraints that make it hard for players to achieve that objective. All mechanics and art must serve this basic feeling.

Accept that you’re using blunt instruments for a finesse operation. Accept that using limited mechanics can cause unforeseen consequences in gameplay. Accept that people will horribly break your game. Accept that your rules are borderline unreadable. Keep going. These kinks will work themselves out with time, feedback, an open mind ready to receive and process that feedback, and hard work.

Take risks. Try things you don’t think will work. Try things that go against traditional wisdom. One of the most praised mechanics of War Co. is that the number of cards you have left is effectively your life. You win by causing your opponent to run out of cards faster than you, often at random. This thwarts the idea of relying on specific combos to win like you might do in games like Magic: the Gathering or Yu-Gi-Oh! because it forces players to abandon the assumption that a certain needed card will eventually turn up. By all means, this shouldn’t have worked. I didn’t expect it to. Even still, I gave it a try and ironed out the details over 7 more versions of the game until it “felt right”.

Trust that you will arrive at your destination. There may be delays. There may be unexpected layovers and missed connecting flights. You may have to circle the airport a few times.

Your destination won’t look like what you first imagined, but it will be better. Strap in and enjoy the journey. It’ll make you a better person. It’ll make your game a better game.

3 thoughts on “Find Your Destination by Making Wrong Turns”

Brandon I like how you used the term iteration rather than redesigns. 17 doesn’t seem like alot but at the same time the. Constantly hear this idea being tossed around that a first game wont resemble a last game at all, I feel thats a bit loose with the lingo, I’m running a first prototype playtest this Sunday, I’m excited more than In nervous, I want to get past the clunky stage, but my core mechanics are set, I could not imagine my game changing a whole ton out side of cleaner mechanics and more stuff. So my question is what should I be looking for in this first wanted of playtesting, dont I want the game to break early and often and if it does wont that mean mu cards are off not the mechanics, how do I tell?

Hi Kevin! Glad you like my take on iteration vs. redesign.

Speaking in generalizations, when you’re early in play-testing, you definitely want the game to break early and often. Now, naturally, every game develops in a different way and you have to play it a lot by ear when you’re figuring out exactly how it’s going to work. But my general rule of thumb for diagnosing an issue with a mechanic (as opposed to rules) is as follows:

“Do I need a bunch of rules to make this mechanic work?” If so, I’d usually drop the mechanic.